There’s an understandable sense of urgency when lawmakers talk about the state’s finances, or educating its children or funding its social services. But at least one state senator is talking about something else.

“There are kids being trafficked,” says Sen. Jeanne Kohl-Welles, D-Seattle, who’s soft-spoken until she gets to this issue. “It exploits women and men, girls and boys.”

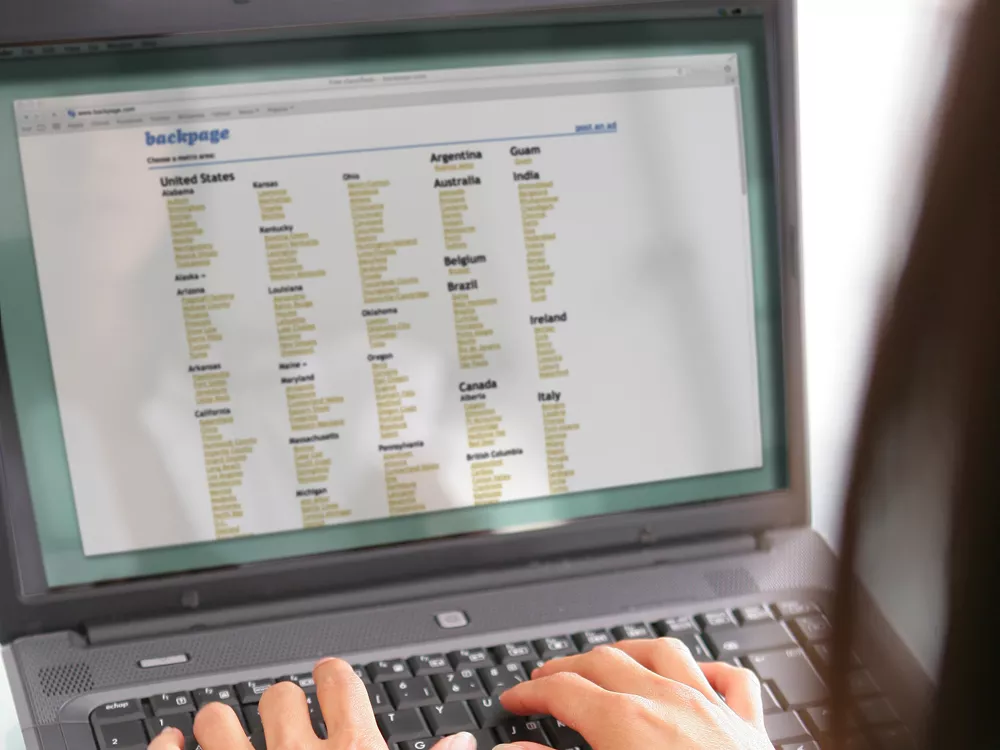

Last session, Kohl-Welles sponsored SB 6251, a bill targeted at sites like Backpage.com for their role in sex trafficking of minors. The law criminalized causing or aiding the sale of sex with a minor and was aimed at forcing sites like Backpage.com to verify ages or shut down their adult sections entirely. It was hailed nationally as the first of its kind, uniquely able to go after the long-elusive online sale of minors. But soon after the bill was passed, it was challenged in federal court and swiftly struck down by a U.S. District Court judge who ruled it unconstitutional. Now Kohl-Welles and her allies are left to repeal one of their proudest accomplishments and figure out what to do next.

“We worked very hard to have a bill that would pass constitutional muster. We thought we had it right,” Kohl-Welles says. “I don’t think it was a weak bill, but it was a difficult bill.”

According to challengers and the judge, the law’s downfall started with how broadly it was written. It could have swept in Internet providers and sex ad-free sites if they host other people’s (potentially illegal) content. Along with Backpage — a Craigslist-like classifieds site with “adult” and “escorts” sections — the Electronic Frontier Foundation challenged the law on behalf of the Internet Archive, which catalogues millions of sites on its Wayback Machine.

General counsel for Backpage Liz McDougall called the legislation “regrettable, shortsighted and ill-informed.”

But it’s unlikely that pushback against Backpage is over. Kohl-Welles says she hopes to introduce another, similar bill in the coming session, which begins on Jan. 14, and says she’s working with state legal staff to come up with better language. (Though neither she nor Dan Sytman, an attorney general’s office spokesman, would give specifics about what that language might look like.) Other states, including Connecticut and Tennessee, have considered similar bills.

McDougall says lawmakers need to invite sites like Backpage to the discussion to “better understand the Internet.”

“The reality is it’s not possible in the Internet realm to review every bit of third-party content,” she says. “The result would be that what’s allowed on the Internet is whittled down to only the most innocuous content. We felt we had no choice [about challenging this bill].”

In January 2012, Backpage made about $2.6 million from ads for prostitution or body rubs (ads range from $3 to $15 each), according to classified advertising consultants The AIM Group, the only group to report detailed stats about the site.

“It does not require forensic training to understand that these advertisements are for prostitution,” reads a letter to Backpage signed by 46 attorneys general, including Rob McKenna, last August. “This hub for illegal services has proven particularly enticing for those seeking to sexually exploit minors.”

New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof called it a “godsend to pimps, allowing customers to order a girl online as if she were a pizza.”

But Backpage is also a marketplace for completely legal sales — adult services like phone sex and stripping, and the type of miscellania you’d find on Craigslist. McDougall says it regularly turns over information on ads it believes to be for minors, a luxury authorities may not enjoy if advertisers migrate toward offshore sites.

“It’s this sort of Brave New World,” says Gonzaga Law Professor Mark DeForrest. “As technology has arisen, legislators are trying to deal with problems that arise with that new technology. Sometimes they’re not really certain where the boundaries are around the First Amendment.”

Washington has a reputation for taking action on sex trafficking issues. The state was ranked first this year in state ratings given by the Polaris Project, an advocacy group that pushes for laws against human trafficking. The ratings gauge states on whether they have a legal framework that “combats human trafficking, punishes traffickers and supports survivors.”

Kohl-Welles acknowledges momentum on the issue could lag with budget issues distracting lawmakers from policy changes, but she’s not letting up.

“I’d like to get to a point in society when there is no sexual exploitation, but I don’t know that that’s going to happen,” she says. “In the meantime, I will do everything I can to stop sexual exploitation of minors.”