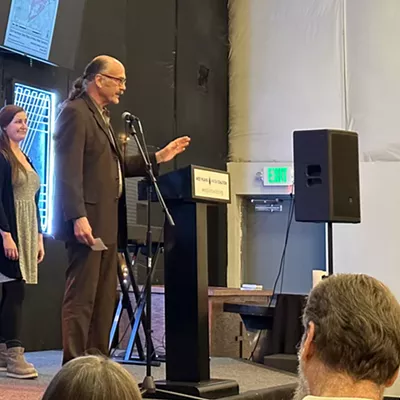

Tom Bailie tells his story to anyone who will listen. These days, few people do. Everyone has died, moved away or just moved on, but Bailie can't seem to do the same.

"I still haven't reconciled with all the anger," says the 56-year-old farmer, standing in an unplowed field on his childhood homestead. "I've not been able to handle that properly yet. And I need to."

And so Bailie tries to talk it out, to keep his rage in check. He tells scary stories of growing up on a farm in southeastern Washington, directly across the Columbia River from the Hanford nuclear reservation. At the age of 5, he nearly died from an inexplicable paralysis and recovered only after spending two weeks in an iron lung. He had asthma, sores across his body and, at 18, was told that he was sterile.

He blames Hanford's radiation releases during the 1940s and '50s. "They were using us as guinea pigs, and they did it deliberately," he says.

Still, Bailie counts himself among the lucky ones. His father and four uncles had cancer; so did his grandparents. And his other neighbors along Glade Road in Mesa, Wash., have had their share of ailments. Several died young with cancer, many women suffered through miscarriage after miscarriage. In one family, a baby was born without a skull; in the house next door, another was born without eyes.

In all, Bailie says, 27 of the 28 families living nearby have had cancer, thyroid disease or birth defects. The narrow stretch of road passing before his childhood home has been dubbed the "death mile." But while Bailie is widely credited with helping to expose Hanford's past, no one wants to listen to him unearth history. Most of all, people are tired of all his moaning.

"We're not complainers, like that Tommy Bailie," says Bernice Ririe, 83, who lives next to the Bailie family farm. Her husband, Howard, died three years ago after a stroke and two open-heart surgeries. Her daughter-in-law, Brenda, is the woman whose baby was born without a skull. "Certain illnesses run in some families," she says. "But Hanford isn't behind it."

Even now, nearly 20 years after the Energy Department confirmed it had knowingly spewed radiation across portions of Washington, Oregon and Idaho, Hanford remains a byword for controversy; the town of Richland exists as a world all its own. Like dust in the desert, the place swirls with intrigue and conspiracy theories, with cutting-edge science and fear left over from the dark days of the Cold War.

To this day, the community is divided between us and them, scientist and farmer, patriot and victim.

There are signs of change. Hanford stopped producing plutonium in 1987 and has since become the world's largest environmental cleanup project. Last year alone, it required more than $2 billion; as a result, the Bush administration is looking for ways to cut costs.

Thousands of new workers flock to the area for cleanup-related jobs. At the same time, the Tri-Cities of Pasco, Kennewick and Richland have slowly developed other sectors of the economy, preparing for the day decades from now when Hanford-related paychecks will cease.

But for those living downwind of the 586-square-mile nuclear reservation, the sins of the past may be history, but they continue to suffer from their effects, both physical and psychological. A lawsuit against the federal government was swiftly dismissed; their case against the corporations that operated the site marches on, now into its 13th year.

"I think they're waiting until we all die, because we're doing it pretty fast," says Louise Winebarger, 80, a downwinder living on the death mile.

X X X X X

In January 1943, Hanford was selected as the site for the world's first full-scale nuclear reactor, in part because the region was isolated and sparsely populated, thus minimizing the potential fallout from a nuclear accident. Leaders of the Manhattan Project, the secret program to develop atomic bombs, were also lured there by the Columbia River, which provided plenty of water and electricity.

Richland became a government-run town overnight, and construction of the Hanford "B" reactor began in March. Two years later, in July 1945, plutonium made at Hanford powered the world's first atomic explosion in the New Mexico desert. Then, on Aug. 9, more was used in the bomb called "Fat Man" that leveled Nagasaki, Japan, and ended World War II.

Over the next 40 years, the site produced at least 53 tons of plutonium, arming more than 60 percent of the nation's nuclear arsenal. During that time, officials at Hanford consistently claimed that people living beyond its boundaries were safe -- a claim they had no facts to back up.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) first acknowledged in July 1990 that the doses of radiation emitted by Hanford in the 1940s and '50s were high enough to cause illnesses, including cancer, in those downwind from the facility. Most of the radioactive emissions were of iodine-131, a byproduct of processing plutonium.

The iodine would blow out of smokestacks and settle on farms and fields where goats and cows grazed, transferring the poison to milk. The chemical would then collect in people's thyroid glands, increasing the risk of cancer and disease. Some young children, whose thyroids are more sensitive, absorbed radiation equal to 10,000 chest X-rays.

From 1944 to 1947, Hanford officials authorized the biggest releases of radiation, at least 400,000 "curies," a unit of radioactivity. To put that amount in perspective, the 1979 accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant discharged just 15 curies.

The series of admissions came four years after the federal government declassified thousands of pages of environmental reports on Hanford's operations. Besides substantiating accidental radiation releases, the papers also showed deliberate experiments, among them the so-called Green Run in 1949.

In that incident, scientists had wanted to test equipment that would be used to measure emissions from Soviet nuclear facilities, so they released about 8,000 curies of radiation during two days. That radioactive plume reached as far as Spokane and southern Oregon.

Gen. Leslie Groves, the military leader of the Manhattan Project, writes of the Cold War mentality in his memoirs: "Not until later would it be recognized that chances would have to be taken that in more normal times would be considered reckless in the extreme."

The disclosures by the Energy Department validated residents' worst fears -- that the government they patriotically supported and the region they loved had poisoned their families, both by accident and by design. Juanita Andrewjeski, 74, had long suspected something wasn't right and began charting the cases of cancer and heart ailments among her neighbors along the river.

"We were concerned because all these young fellas had these heart problems," she says. "Some just keeled over."

Walking across dirt he played in as a boy, Bailie recalls the impression he had of Hanford then. "We were so proud just to be close to it," he says.

Of course, there were days most American kids never experienced. Mornings when the snow was pink. Years when livestock were born deformed. Occasions when scientists walked through the wheat in space suits.

"But we didn't worry about it," Bailie says. "Our job was to grow food. Their job was to keep the Communists from taking over the country."

Lawsuit -- Some who grew up in Hanford's shadow say they were poisoned, but despite admitting to massive releases of radioactive material, the federal government doesn't believe them. A month after federal officials acknowledged that downwinders had been exposed to dangerous levels of radiation, several lawsuits were filed against the private contractors that had managed the site for the government during the previous four decades.

The suits were later consolidated into one case, which is still undecided today. Several of the attorneys involved wonder whether it will ever see trial.

"I am a firm believer in settlement," says Louise Roselle, the downwinders' lead counsel, who is based in Cincinnati, Ohio. "There is no other alternative realistically available."

Early on, the suit swelled to 5,500 plaintiffs, but over time has been winnowed down to those people who received the largest doses of radiation and whose illnesses can be scientifically tied to radiation exposure. In November, the number of active plaintiffs dropped to 1,816, most of whom suffer from thyroid problems.

Many other downwinders feel excluded, their suffering ignored, and Roselle says there is little she can do to mollify them.

"People want an explanation for what happens to them in life," she says. "If you get a disease, you want to know why. Something like Hanford explains it.

"But that doesn't mean when you go to a court of law, you can prove it."

Roselle helped litigate a case in Fernald, Ohio -- 18 miles northwest of Cincinnati -- where 14,000 people downwind of a uranium plant successfully brought the government to a settlement of $78 million in 1989. In that case, attorneys argued that the plant had lowered plaintiffs' property values and inflicted emotional distress. That, Roselle admits, was easier than linking the plant to people's medical conditions.

The cornerstone of the Hanford downwinders' lawsuit is this: "These radiation releases occurred, the public wasn't told, the people got sick and there is more illness in the community than there should be," Roselle says.

Attorneys for the other side accept all of those claims except for the last one -- that illness rates in downwind communities are significantly higher than in the general population. They don't deny that certain individuals were affected, but maintain that the number is low.

Kevin Van Wart, lead counsel for the three companies named in the suit, contends the case has taken so long to litigate because plaintiffs' attorneys failed to weed out erroneous claims. In the beginning, he says, the suit even included a woman whose complaint was that lights would turn off when she entered a room.

"It was almost as though everyone with cancer or any other condition was trying to blame Hanford," says Van Wart, who works for a Chicago-based firm.

Van Wart represents General Electric Co., DuPont and United Nuclear, which managed the site during the heaviest polluting years. In an agreement made during the Manhattan Project, however, all legal fees are to be paid by the federal government. The tab has already exceeded $60 million. (The government would also have to cover any judgment made against the contractors.)

Van Wart believes the suggestion of a settlement is "grossly premature." He concedes that radioactive iodine can cause cancer, but says the downwinders' attorneys have not established the link between the dose of radiation each person absorbed and the resulting medical problems.

The contractors' strongest defense, Van Wart says, is that they were doing the federal government's bidding during a time of national crisis and thus are immune from litigation. He cites a 1991 decision in the U.S. District Court in Oregon that found the government was protected in the Hanford case by the "discretionary function exception."

"They're trying to try the case on hindsight, leaving out the wartime urgency, the Cold War urgency," says Van Wart. "If people at Hanford were deliberately overlooking people's health, then that would be one thing."

X X X X X

The downwinders' case first appeared before U.S. District Judge Alan McDonald, who in 1998 dismissed thousands of plaintiffs on the grounds that they failed to prove that their radiation doses had doubled their risk of contracting cancer, a standard he himself had set. McDonald also ruled that the technical evidence of radiation injury was too complicated for a jury to consider.

His decision was appealed and overturned last year by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Then, in January 2003, McDonald recused himself from the case after attorneys learned he had purchased an orchard near the "death mile" and certified to a bank that the property was radiation-free.

The case was reassigned in April to U.S. District Judge William Fremming Nielsen in Spokane, who quickly consolidated the various lawsuits. Nielsen also decided to begin with a dozen "bellwether" cases, which will be used as a guidepost for the rest of the claims. The trial is set to begin in March 2005.

Still at dispute in the case is a controversial $20 million report called the Hanford Thyroid Disease Study, which was released last year by the federal government's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It found no link between the amounts of iodine-131 people received and thyroid disease.

"If there is an increased risk of thyroid disease, it is too small to observe," says Paul Garbe, the CDC's scientific advisor.

Because national statistics on thyroid disease don't exist, Garbe says researchers had to estimate the prevalence of the disease in the general population. And compared with that estimated rate, the study group of 3,441 downwinders did not have an unusual occurrence of thyroid disease.

The study did note a death rate 20 percent higher than normal, mostly from birth defects and complications late in pregnancy. But researchers believe it was unrelated to thyroid disease or iodine-131 because of the timing of Hanford's emissions.

The National Academy of Sciences reviewed a 1999 draft of the CDC report and found it to be well designed. But the academy concluded that the CDC's presentation of the findings had overstated their certainty. The analysis had depended on radiation-dosage estimates, which are disputed by some scientists, the academy says.

The raw data at the CDC has not been opened up for review, Garbe adds, because it was collected under "strict federal assurances of confidentiality."

Van Wart calls the thyroid study a "major obstacle" for the downwinders. Roselle maintains that "there isn't really any question that there is an increased rate of disease in the area."

The trial is shaping up as a battle over science, with dueling experts trying to convince a jury whether there was a cause-and-effect relationship between Hanford's releases and the illnesses suffered by its neighbors.

For their part, few downwinders seem to believe their case will prevail. Bailie, who has been removed as an active plaintiff, says he only wants access to free medicine and medical care as "veterans of the Cold War." Andrewjeski, who continues to take thyroid medication, says she signed up with a lawyer during the early '90s but hasn't inquired about her status in years.

Louise Winebarger, another death mile resident, wonders what would be gained by continuing with a trial at this stage. Her husband, John, is dead. Her own body is breaking down. The farm is faltering. "Would the further loss of confidence in our government be worthwhile?" she asks.

Sitting in her kitchen, she considers her own question and then thinks of her granddaughter, Jamie, who was born with one particular defect. "I just wish they could put her eyes back," she says.

The case is being monitored across the country, because it could set a precedent for how people living next to nuclear plants are ultimately compensated. If the Hanford downwinders succeed in court, their judgment is expected to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Cleanup -- It's a massive project, and the federal government wants to cut costs, shorten the timeline and, some worry, turn Hanford into the nation's nuclear dump. After 40 years of processing plutonium, workers at Hanford will spend at least that much time -- and perhaps considerably more -- cleaning up the aftermath. It is the most polluted place in the Western Hemisphere. Among the hazards are 53 million gallons of highly radioactive waste in 177 huge tanks, many of which are known to be leaking. More than a million gallons have already seeped into the soil and threaten the Columbia River.

The course of cleanup was initially outlined in the 1989 Tri-Party Agreement between the DOE, the federal Environmental Protection Agency and the Washington Department of Ecology. Under that schedule, cleanup would be completed by 2070 at an estimated cost of $90 billion.

The Energy Department, however, now wants to scrap that plan in favor of an accelerated timetable that would push work to be done by 2035, maybe even by 2025, and cost only $50 to $60 billion. DOE officials say speeding up work and cutting expenses is the only way to ensure that the project will be finished.

Tom Welch, a DOE spokesman, says the new plan "demonstrates the Bush administration's commitment to accelerated cleanup and ensures progress long sought by the department, the EPA and Washington state."

Hanford watchdog groups and others in the community worry that acceleration is actually a codeword for cutting corners, shortchanging the environment or simply walking away from the problem. Tom Carpenter, director of nuclear oversight for the Government Accountability Project, a nonprofit group, believes the administration "wants to get out of the cleanup game as soon as possible."

"You have to ask the question: What are they leaving behind?" Carpenter says. "What are they not doing? And the answer is huge."

At the center of DOE's accelerated cost-saving plan is reducing the amount of liquid waste that must be "vitrified," a very expensive process that embeds long-lived nuclear garbage into stable glass logs that are later buried deep underground.

To that end, the Energy Department published internal rules in 1999 allowing it to reclassify some of the material in the tanks as "incidental." The change in definition would free up the department to cover the waste with a cement-like material and leave it in the leaky tanks.

Environmental groups challenged the DOE's authority, saying the federal government was audaciously playing with semantics to shirk its responsibility. In July, Judge B. Lynn Winmill of U.S. District Court in Boise, Idaho, agreed, overturning the department's approach, saying the reclassifications were based on little more than "whim."

Welch, the DOE spokesman, would not say whether the department would appeal the court's decision or directly lobby Congress to change the law. "We are still reviewing all our options," he says.

The Energy Department is also facing a legal challenge regarding the shipment of radioactive waste from other sites to Hanford. Washington State Attorney General Christine Gregoire sued the DOE in March and received a temporary restraining order stopping the import of "transuranic" waste -- plutonium-contaminated trash.

A coalition of environmental and peace groups is also working to get an initiative on the November ballot that would block the Bush administration's plan to ship 70,000 additional truckloads of waste to Hanford. As of this week, they've collected 175,000 signatures and have until the end of December to get 25,000 more.

"We think this will stop the DOE from making Hanford one of the nation's radioactive dumps," says Amber Waldref, a field director for Heart of America Northwest, one of the initiative's sponsors. "We just want them to clean up existing waste before adding any more."

DOE Spokesman Welch would not comment on questions about the restraining order or the proposal to ship thousands of truckloads of waste to Hanford.

X X X X X

Driving across the Hanford site, you get an idea of how massive the place is. There are 1,400 buildings -- 400 that are considered radioactive -- but they're clustered together. The majority of land is covered only in sand and sagebrush. Tumbleweeds roll across the roads. There are no trees.

By visiting Hanford, you also begin to understand the challenges facing cleanup crews. Scientists here have to think big -- not in terms of their lifetime, but in tens of thousands of years. Many projects start before the designs are complete, as they may depend on technology that has yet to be invented.

Take, for example, the $5.7 billion vitrification plant, which will turn waste from the tanks into stable glass logs. The project broke ground in October 2001 and today the design of the facility is only about 60 percent complete, says John Britton, a spokesman for Bechtel National, which took over the job from another contractor.

It's a way to ensure that at each stage of construction the latest technology is used, Britton says. Regulators have also agreed to review the design in stages and issue permits as construction proceeds. The plant is scheduled to begin operations in 2011.

The approach also helps contractors at the negotiating table, Britton says. Each year they must ask for the money to continue work and there is always fear that the politics of cleanup will change or that funding will simply be pulled.

"Without showing something coming out of the ground -- concrete being poured, steel being laid -- it's really hard to make a case for funding," Britton says. "You've got to show progress."

The tactic has some drawbacks: More than one plan to deal with tank waste has been discarded, costing both time and money.

While some new construction is being done, efforts continue to "decommission" and destroy the infrastructure left behind from Hanford's production years. In October, workers began to dismantle a plutonium processing plant, which represents two milestones for the site: It is the first plutonium facility to be destroyed at Hanford and the first one demolished in open air anywhere in the country.

Before beginning work, a fixative was applied to the walls to glue down contaminants and, as a wrecker shears the walls, a soapy mist is sprayed into cracks to prevent chemicals from flying away with the wind, explains Jeff Riddelle, deputy project manager of the demolition.

Using this technique, Riddelle says, is faster, cheaper and safer for workers who spend less time in close proximity to the radioactive building. Plus, without a tent, there is less trash to throw into the Hanford's landfill.

The open-air model is being monitored by officials at other DOE sites, Riddelle says, and will likely be employed in future demolitions at Hanford.

The nuclear reactors themselves are being "cocooned" for temporary storage; three of the nine are already finished. The process involves destroying secondary buildings, sealing holes with heavy concrete and putting on a new roof of galvanized aluminum that should last for several generations, says Michael Mihalic, a project manager.

"They don't guarantee it, but tests around here have shown that it will last up to 75 years," says Mihalic.

What will become of Hanford's "B" reactor -- the world's first full-scale reactor -- is still unknown, but there is talk of making it into a museum, a tourist attraction for Cold War buffs.

Atomic Culture -- Being able to laugh at tragedy may be a sign that healing has occurred -- but not everyone is laughing yet. Hanford may no longer build the bomb, but Richland is still the "Atomic City." Thousands of Hanford's workers continue to live in its government-built houses. The economy surges and slows according to developments at site. It accounts for about half the jobs and two-thirds of the wages in the city of 37,000.

Hanford forms a substantial part of the region's identity, residents say. Even the streets bear the signs of atomic energy. In one neighborhood, there's Nuclear Lane, which runs next to Proton Lane and Mercury Drive. And then there's Richland High School, with its school symbol of a mushroom cloud and sports teams called the Bombers.

"You tell people you're from Richland and you get blank stares," says Dave Acton, 37, brewmaster at the Atomic Brewpub and Eatery. "Then you say the Tri-Cities; more blank stares. Then you say Hanford and people begin stepping back."

Acton has a sense of humor and likes to exploit Richland's history. Glow-in-the-dark jokes? His response is well practiced.

"We don't make bombs anymore," he says, "but we could. So, watch out!"

The brewpub serves what you might expect, dishes like Positron Pineapple Pizza and B Reactor Brownies. It specializes in homemade beers called Plutonium Porter and Half-Life Hefeweizen, which, Acton tells new customers, are "brewed with the local water for that extra buzz."

His recommendation: "The dark beer -- it takes radiation out of your body," he says. "Or at least that's what the guys with badges tell me."

Michele Gerber, author of On the Home Front: The Cold War Legacy of the Hanford Nuclear Site, believes the region will eventually be forced to diversify its economy. Fifty years from now, she says, the region will be a destination for eco-tourism and a site of pilgrimage for those interested in the history of the atom.

"No one can understand the 20th century unless they understand the Cold War," Gerber says. "And they can't understand the Cold War unless they know about Hanford, because we epitomize it. We were the battlefield of the war, and that has to be interpreted just like Gettysburg."

X X X X X

Tom Bailie knows the history of the atom. Not only has he visited Hiroshima, but when Japanese survivors from both Hiroshima and Nagasaki came to the Tri-Cities in 1988, he took them in a school bus to see death mile. He told them about his family and his neighbors. Bailie didn't have to explain or defend his story, he says. They understood.

"Their faces were pretty white at the end of it," he recalls. "They realized what had taken place with the American people here, that there had been suffering here to build the bomb."

Many of Bailie's neighbors, though, called him a traitor for associating with the Japanese, America's old enemy -- the reason, people said, Hanford was created in the first place. "I am a pariah here," Bailie admits, gesturing to endless fields and dozens of farmhouses. "My neighbors hate my guts."

Despite helping uncover Hanford's shadowy past, locals continue to criticize him for stepping into the spotlight, for risking their farms and their livelihood over something that happened 50 years ago.

"I've been vindicated," says Bailie, "but not forgiven."

Over time, he has watched as once vocal downwinders have given up, turned silent and thrown themselves back into farming with thought of little else. "You have to resume a life, normalcy of some sort," Bailie acknowledges.

"They all got tired of constantly defending their patriotism, their sanity or whether they were fanatics or whether they were greenies or, God forbid, an environmentalist who was looking for clean air," he says. "Things like that don't sit well here."

But hard as he tries, Bailie can't move on. His sense of justice prevents him. He says he has read too many books and seen too many government documents on the nuclear program that refer to the "low-use segment of the population," a group he says includes him.

"They decided that we were expendable," he says. "They used us, and it wasn't right.

"They killed the cows. They killed the sheep. They poisoned the wheat crop," he continues. "And they all got good wages, and we're still broke."

Bailie now worries that the Tri-Cities, his home since birth, will be turned into a "national sacrifice zone," that the federal government will one day walk away from its responsibilities at Hanford. After what's happened, he says, it's hard to trust anyone. But perhaps talking himself out onto a limb again, Bailie backs up.

"I'm not a scientist and I'm not an educated man," he says, tossing up his hands. "Just a storyteller. And that's my story."

The Green Run -- When federal DOE officials declassified thousands of old Hanford documents in 1986, it was the Green Run experiment that most outraged people across the country. Even The New York Times published a story under the headline, "1949 Test Linked to Radiation in Northwest."

According to the government's documents, the experiment spread radiation above existing "tolerance levels" as far as The Dalles, Ore., and Kettle Falls, Wash.

It was called the Green Run because the uranium that was processed had been out of a reactor for only 16 days, rather than the usual 90, making it even more potent. The purpose: to track and measure the radioactive plume in order to develop methods of estimating production at Soviet atomic bomb plants. The Green Run wasn't about developing nuclear weapons; it was about spying on the Soviets.

One of the reasons the experiment was performed in December, Hanford officials said, was that cows would not be grazing in nearby fields, perhaps suggesting that Hanford officials did have concerns about the health impacts of the releases.

Juanita's Map -- After her husband, Leon, was diagnosed with heart disease in 1976, Juanita Andrewjeski began to track the illnesses of her neighbors who lived just across the Columbia River from Hanford, near the town of Mesa and what has been called "death mile."

She noticed clusters of people suffering from heart attacks and cancer. Below is a reproduction of her original map, detailing the known illnesses as of the mid-1980s.

Andrewjeski's amateur map became very influential in the early days as the Hanford story was emerging. It was reproduced in newspapers across the region as anecdotal proof that something was very wrong. Still, the federal government's Centers for Disease Control concluded that the instance of thyroid-related illnesses was no greater near Hanford than in other parts of the country. Those findings, however, are still in dispute.

"We knew Hanford was there and heard it had made the atomic bomb," Andrewjeski recalls. "But maybe like moles, we didn't think about it."

Her husband died in 1991 at age 71. Andrewjeski believes Hanford shortened his life and the lives of many farmers she knew. These days, though, she just tries to keep busy and to keep her aches and pains at bay.

"I kind of keep quiet because I don't want to get people upset," says Andrewjeski, 74.

Underground Tanks -- Each plutonium processing plant at Hanford has a designated "tank farm," a series of huge tanks buried about 10 feet underground and used to store the plant's liquid wastes. Of the 177 total tanks -- some of which are as big as the Capitol dome in Olympia -- at least 67 are believed to be leaking. Already, a million gallons have contaminated the soil.

Officials at CH2M HILL, the contractor in charge of the tanks, say that 98 percent of pumpable liquids have been removed from the site's single-shell tanks and put into double-shell containers, which officials say have never leaked. That process is designed to reduce the threat to the Columbia River.

What's left behind now are radioactive sludges and salt cakes, and in a Hanford milestone, workers have finally begun to remove that material, says Mike Berriochoa, a company spokesman.

"These are the first two tanks to be emptied, but they're two tanks more than anyone else has ever done," says Berriochoa.

Who Gets Compensated? -- The story of the downwinders' 13-year-old lawsuit, among many other issues, raises two thorny questions: How much is pain and suffering worth? And when should Congress intervene on behalf of victims and compensate them or their families?

History offers no clear answers.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, Congress quickly created the Victim Compensation Fund for families of those killed in the Twin Towers and the Pentagon. So far, about 1,800 families have participated, each receiving on average $1.7 million. On the other hand, aid hasn't been given to Oklahoma City bombing victims or to survivors of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

In 1988 -- as revelations about Hanford surfaced -- Congress passed legislation apologizing to Japanese-Americans who were interned during World War II. Each internee received $20,000.

And Hanford workers have fared better than those who lived nearby, as compensation plans for workers' health have paid out over the decades with a relatively low threshold of proof required to access the funds. Those benefits, however, were arranged ahead of time. Those seeking compensation after the fact, however, have only two choices: They can choose the courts, as Hanford downwinders have done, or they can seek the support of politicians. Winning over political operatives, never an easy task, may provide downwinders with their best hope for compensation.

Comments? Share them with us at letters@inlander.com

Publication date: 12/04/03