Wylie Hunter refuses to give up.

It all started almost two decades ago, when Hunter was pulled over while driving a rental car through Kootenai County and his life changed forever.

Sure, he'll admit that on Sunday of Labor Day weekend 2007, he had 75 pounds of marijuana in hockey gear bags in the trunk of that white Chevy Impala.

All that weed didn't get vacuum sealed in plastic bags, coated in wheel bearing grease, then vacuum sealed again by accident: He knew that he was illegally taking hydroponic B.C. Bud from Canada to Arizona. Officers estimated those bags had a street value nearing a quarter of a million dollars.

But the questionable pretext that led to his car getting searched all those years ago, the perjured testimony he claims was presented during his case, and the lasting health impacts of his incarceration have eaten at him over time.

Within days of being booked into Kootenai County Jail that September, he contracted a horrible antibiotic-resistant staph infection (MRSA) that stuck with him for well over a year, ruining the hearing in his left ear, damaging his teeth and leaving his left foot improperly healed from sores and brittle bones, with no options for surgery.

While he was in prison, his wife divorced him. He blames the fear of future contact from law enforcement.

And in the many legal filings he's made since his conviction, he says he feels the courts have stonewalled him as he's tried to introduce evidence that would've been essential during his case — things his attorneys should've brought up.

"They used this to destroy 15 years of my life," Hunter says. "This is a marijuana case we're talking about, no guns or anything."

After a conditional guilty plea that allowed him to appeal, Hunter was sentenced for felony marijuana trafficking in 2009 and served 10 years, including the two he spent in jail while his case played out. He got out in 2017 and finished parole in August 2022.

He no longer needs to engage with the criminal justice system.

The thing is, though, all those pieces that went wrong along the way planted a seed that has grown into an all-consuming quest for vindication.

While most people would've walked away by now, trying to avoid ever stepping foot in a courtroom again, Hunter has taken the opposite approach, trying as hard as he can to get someone — anyone — in the court system to throw out his conviction.

Lately, he's focused his efforts on arguing that the judge who oversaw the majority of his case improperly assigned himself to hear it. In a civil case, Hunter claims that was a "plain usurpation of power," which entitles him to a "void judgment."

The state disagrees, and judges continue to deny his legal requests.

In fact, Hunter has done so much work representing himself in "pro se" civil filings over the last two years that in February, the prosecutor's office for Kootenai County took the rare step of asking a judge to declare him a "vexatious litigant."

The judge agreed that Hunter's recent claims have been "unmeritorious" and passed the matter off to Kootenai County's administrative judge, who could require Hunter to get court approval before he's allowed to file anything else.

Yet even that hasn't deterred Hunter.

He's dead set that the process was not followed properly during his case or after his conviction, and he believes he is entitled to recourse.

"I've experienced judicial corruption from the judges and prosecutors throughout my entire case. It's gotta be stopped," Hunter says. "They've gotta be exposed."

WHEELIN' AND DEALIN'

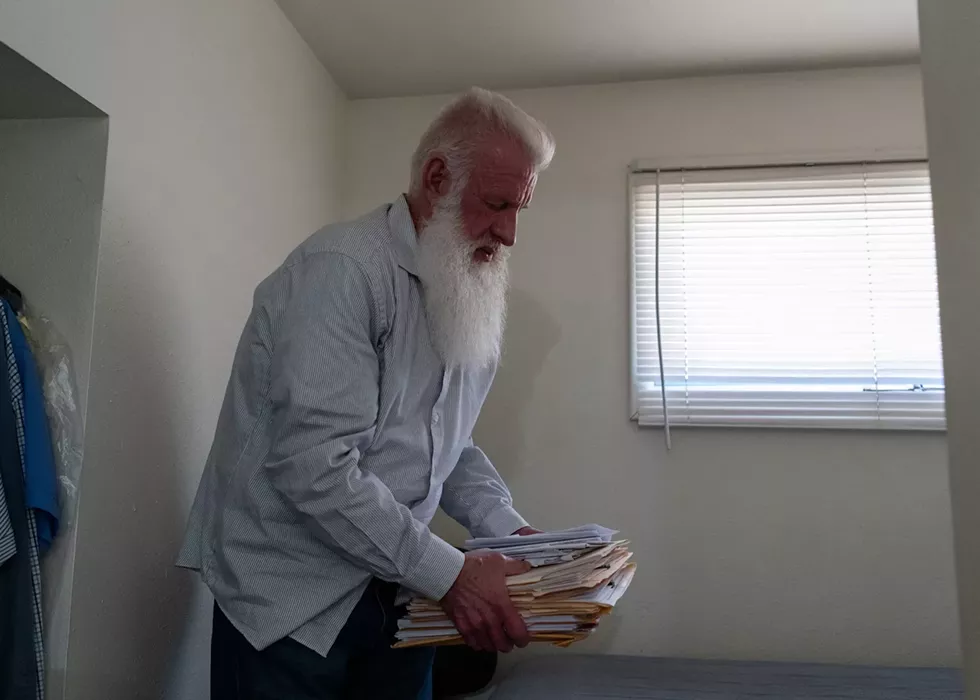

At 68, with a long white beard and a vaguely Southern twang, Hunter's generally a likable guy. Speak with him for a few minutes and like many of the people who happen to cross into his orbit, you'll learn he's got a knack for getting people to turn a sympathetic ear.Over the years, he's told multiple reporters about his case. He's made friends with people at the gym by talking about his experience. He's well known around the courthouse and clerk's office, where he so often goes to file the latest paperwork.

You might notice a near obsession with the phrases "usurpation of power" and "void judgment," the two things he's been arguing most vehemently since 2022. And the gentleness might crack into anger or frustration if you question his chances of winning that void judgment.

These days, Hunter lives in a humble yellow backyard garage in Coeur d'Alene that's been converted into a one-bedroom. Inside, his room is just big enough for a twin-size bed; his handful of shirts hang tidily in a small inset cubby in the wall. He's got a bathroom with a small shower and a kitchenette with a fridge and a microwave. The heat works, and he even got an air conditioner last summer.

"I got a safe place to sleep, and I'm by myself and not with other people," Hunter says. "I have everything I need here."

When he's not working from the library, he works from the couch in his living room, bent over a makeshift coffee table made from a ventilated plastic shelf full of holes. Hunter says he doesn't really know how to operate a computer, so he handwrites (and rewrites, and rewrites) his court filings before sending them to a woman he pays a small fee to type them up for court. Stacks of manila folders around the apartment contain hundreds of pages of court filings from the last 17 years.

Day to day, he gets by on less than $1,000 a month in Social Security and food assistance. But he doesn't complain about his current living situation — "sure beats a prison cell" — even though it's a far cry from what he had at the height of his life.

"I'm blessed to have what I do have," he says.

Hunter grew up in Arkansas until about the third grade, when his family moved to Ephrata, Washington, just north of Quincy and Moses Lake. In his youth, he "was always wheeling and dealing cars," buying up mostly older Corvettes and Chevelles, fixing the body work, then detailing and selling them from his small car lot.

In 1989, he moved his young family to Coeur d'Alene, where he owned a gym for a few years and continued to flip cars with his dealer's license. But his bread and butter through the '90s was importing Harley Davidson motorcycles. At that time, Hunter says that dealerships were only given a small allocation of the new bikes, so waiting lists quickly grew to one or two years long.

Seeing opportunity, Hunter began regularly traveling to Canada to purchase bikes. The motorcycles were made in the U.S., which meant he could get his tax back, and he would overnight new titles from Boise and swap out the speedometers (from kilometers to miles) to quickly ship them off to buyers in the U.S.

"With the [favorable] exchange rate I was probably buying at least 12 Harleys every week," Hunter says.

But that gig started to dry up after larger dealerships opened in the region, and customers easily found new bikes closer to home.

In 2000, Hunter and his wife and kids moved to Scottsdale, Arizona. As usual throughout his life, going to the gym every day was important to him, and that's where Hunter says he started to meet sports doctors who told him about the need for medical grade marijuana. Everyone from veterans to cancer patients could benefit, they told him.

While Hunter says he was never really personally into smoking weed, he thinks cannabis could have helped people like his brother, who had no appetite and dramatically lost weight while receiving cancer treatment before he died in '96.

With plenty of connections in Canada that he'd made through his Harley business, Hunter was able to find serious hydroponic purveyors who were proud of their award-winning strains, and he soon figured he could make green from yet another import.

But the route he chose took him right through Idaho, one of the strictest states in the country for cannabis crackdowns.

ARREST AND AIR CIRCULATION

By the time he was arrested in September 2007, Hunter and his passenger, Chase Storlie, had been on the radar of law enforcement for a while.Then-Idaho State Police Detective Terry Morgan had started an investigation several months prior, partially informed by Storlie's former romantic partner. As detailed in court documents, Morgan learned through the woman how Hunter and Storlie would rent vehicles and stay at hotels during their trips to hike cannabis across the border.

Morgan asked Avis Car Rental employees to call him when Hunter rented a vehicle, and that's how he knew on Sept. 2, 2007, to keep an eye out for a brand new white Chevy Impala with Washington plates.

When Morgan saw the car drive by on U.S. Route 95, he radioed another trooper and said the vehicle had been speeding and made two illegal lane changes, according to court documents. The other trooper pulled Hunter over near Hayden Lake a few minutes later.

But Hunter says he wasn't speeding. Not only were they stuck in holiday weekend traffic, but he was well aware of the risks of violating traffic laws.

"Why would I be speeding with a trunk-load of marijuana?" Hunter asks.

Ronald Sutton, the trooper who pulled him over, would later testify in a hearing that he did not smell weed while talking to Hunter through the driver's side window of the vehicle, nor when he walked by the trunk. He testified that it was only when he spoke to Storlie through the passenger's window that he smelled the faint odor of marijuana.

Morgan arrived at the scene a few minutes later, and within 30 minutes a drug dog was brought out. Officers testified that the dog alerted on the trunk, and they were able to search it. Morgan testified that the trunk was stuffed so full of weed it was hard to get the first hockey bag out.

The state brought in master technician Richard Shabazian, who was certified at the highest level for GM vehicles, to testify about the air circulation system in Chevy Impalas.

"[Air is] circulated from the front to all the way back to the rear bumper through the cabin, trunk, and then out the back corners of the body work," Shabazian testified. "The valves were put in on this particular car for the ventilation in case somebody is in the trunk and the [sensor] system fails. There's a release in the trunk. So a person could actually live in the trunk because there's enough air moving back and forth."

When Hunter's then-attorney asked if the fans needed to be on for air to circulate from the trunk into the cabin while a vehicle is parked on the side of the road, Shabazian said, "No."

"If anything, the odors would go from the trunk to the passenger with it not moving instead of the other way around," the mechanic testified.

That seemed wrong to Hunter and his later state-appointed public defender, Stacia Hagerty. During a March 2018 hearing on Hunter's petition for post-conviction relief, Hagerty argued that the testimony about the circulation system made no sense. She had previously shared a diagram of the car to back that up.

"If you had a gas can or stinky garbage in your trunk, you wouldn't want it to circulate into your car," Hagerty said during the hearing. "I would submit that no car ever had a trunk circulation system that vented into the interior; but that's argument, your Honor, not fact."

"Why would I be speeding with a trunk-load of marijuana?"

QUESTIONS ABOUT THE CASE

The testimony about the smell and the air flow were key elements in Hunter's post-conviction efforts to question whether officers ever had probable cause to search his vehicle. He wanted the courts to suppress the evidence that came out of that traffic stop and led to his conviction.Hagerty had worked on Hunter's case since 2016, sharing evidence with the prosecuting attorney's office along the way that questioned key elements of the state's case.

After sharing some of their findings, Hagerty wrote Hunter a letter in October 2016 about a deal that Kootenai County Deputy Prosecutor Brian Bushling had offered, which would have released Hunter from prison about a year early and closed his case with no parole or probation.

But Hunter declined the offer because the conviction would remain on his record. He said he "wanted the truth to come forward in a new suppression hearing, with the new discovered evidence to be presented in court."

Among the things they'd uncovered was evidence that a state's witness had lied.

An Avis employee testified during the case that a coworker picked up the car from the site of the traffic stop, and the weed smell was so strong they had to drive with the windows down and take the car to Spokane to be detailed.

But Hagerty learned the vehicle was actually taken to the Idaho State Police lot for days before it was returned to the rental company. The mileage on the vehicle didn't indicate a trip to Spokane. And it was troubling that state police had only interviewed the Avis employee in November, months after the stop.

Hagerty also requested a DVD of the video and audio of the traffic stop, but the state informed her the disc was destroyed on Feb. 26, 2013, because it had incorrectly been marked as part of a misdemeanor case.

The video might have backed up Hunter's recollection, which was that Sutton never even went to the passenger side of the vehicle, the one place the trooper claimed he smelled the faint odor of weed.

When it came time for that March 2, 2018, post-conviction hearing (where Hagerty brought up the air flow and other issues in the case), Kootenai County District Judge Lansing Haynes started off by noting that Hagerty had not filed a memorandum outlining some of the new evidence on time, saying he only received it that morning, according to a court transcript.

Hunter tried to fire Hagerty on the spot.

In a sworn statement of facts filed in court, Hunter later declared that after the hearing, Hagerty told him, "Wylie, they threatened to take my State contract unless I filed the Memorandum late. I need the State contract to support my family." She also pointed out that Detective Morgan was in the courtroom.

"The officer who did the investigation showed up at that hearing, which is highly unusual," Hagerty tells the Inlander. "Not only was he retired, but he hadn't been at any of our prior hearings. The judge acted very differently at that hearing than any of our previous hearings."

But Hagerty denies ever saying that she was told to file anything late, and importantly, she says all the evidence was filed on time. She says the memo filed the night before the hearing wasn't a required document, merely spelling out in writing what she planned to say in oral argument.

"Not only did nobody ever threaten my contract, I don't believe I filed anything late," Hagerty says. "I write better than I speak. ... It was to augment the record."

Hunter says he can't understand why Hagerty is now denying the comments about her state contract, which he has included in multiple legal filings over the years.

"I've been presenting the facts," Hunter says.

APPEAL, APPEAL

Hunter has tried to fight his conviction in just about every way he can.In addition to multiple petitions for post-conviction relief made while he was still in custody, Hunter also filed two federal lawsuits.

None of the cases went in his favor.

"All I'm after is the truth."

In Hunter's direct appeal, the Idaho Court of Appeals ruled that "the officers had reasonable and articulable suspicion to stop the vehicle based upon both the prior investigation, as well as the traffic violations."

Detective Morgan was able to verify the details provided by Storlie's ex via hotel and rental car receipts, plus Hunter had received four months in federal prison in 2005 for not reporting a large amount of cash he took across the border, the Court of Appeals pointed out.

In a later filing, Hunter argued that the destruction of the DVD violated his due process rights. Hagerty tells the Inlander the courts should have presumed the video would show what Hunter said it would.

But in 2019, the Idaho Court of Appeals found that Hunter did not prove the DVD would have changed the outcome of his case.

In 2022, Hunter filed a request for relief under a specific portion of the Idaho Civil Rules of Procedure, taking issue with Hagerty's defense, and claiming for the first time that the judge who oversaw most of his criminal case didn't have authority to hear it. That judge was Haynes — the same judge he later had on the post-conviction case in 2018.

While going through the reams of paperwork in his criminal case, Hunter says he discovered that there was no form disqualifying another judge who had been assigned to his case when Haynes took over. The clerk's summary of his record appeared to show that Haynes assigned himself, instead of getting that direction from the administrative judge.

In Hunter's view — informed by a mix of jailhouse lawyer types he met behind bars, his own research, and a few sympathetic ears in the legal world — Haynes violated state policy on judge assignments and opened the door for his conviction to get thrown out.

"He assigned himself to my case," Hunter says.

There was, however, a hearing in December 2007 to join Hunter's case with Storlie's, which was assigned to Haynes. The minutes, which offer an incomplete picture of everything that was said, seem to indicate that attorneys for both men objected. But Haynes signed an order that day joining the cases for trial before him.

Kootenai County District Judge Lamont Berecz denied Hunter's 2022 request, saying the cases were joined.

"The court record would show that you're just clearly wrong," Berecz said in July 2022.

Hunter appealed.

CURRENT CASE

In May 2023, Hunter filed a new case. This time he cited a civil rule pertaining specifically to void judgments and included Idaho case law that says a judgment is void if the "court's action amounts to a plain usurpation of power constituting a violation of due process."Again, Kootenai County Civil Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Jamila Holmes argued in court filings that there was no violation of due process: Haynes joined the two cases in 2007, and Kootenai County had jurisdiction over the case.

"The [state] has been forced to answer and defend against the very definition of a frivolous claim here," Holmes said in court in December 2023, while asking a judge to award more than $700 in fees to make up for some of the costs of responding to Hunter's various filings. (Holmes did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.)

Hunter denies that his case was ever joined with Storlie's, and says that he was never in court at the same time as his co-defendant.

According to multiple attorneys who spoke with the Inlander, even if Judge Haynes did somehow violate the assignment procedure, it's unlikely that error would be enough to get a court to throw out Hunter's conviction.

"Mr. Hunter would have to demonstrate, in my mind, that a judge had been improperly assigned for improper purposes and engaged in improper conduct during the management of the case, before any appellate court would even agree to look at such a remedy as voiding the conviction or the judgment," says Kevin Curtis, who served as a public defender for 14 years and has been a criminal defense attorney in private practice in Spokane for nearly 30 years.

However, Curtis has read thousands of police reports from both Washington and Idaho during his decades in practice. In that time, he says he often saw examples of "pretextual" stops in Idaho, where law enforcement would pull someone over on the pretext of a traffic violation, while in reality they were seeking evidence of some other crime but didn't have probable cause to search prior to the traffic stop.

"Idaho is known for pretext stops, so I understand Mr. Hunter's concerns," Curtis says. "He may well be right, there may have been misrepresentations. There may have been things those people said that were untrue and known to be untrue."

John Rumel, a law professor at the University of Idaho, says that the civil rule Hunter's latest case is filed under doesn't typically apply to criminal cases.

"He is using this rule of civil procedure that only applies to civil cases, and his conviction obviously was in a criminal case, so that's the first barrier," Rumel says.

If Hunter were still under supervision and filing a habeas corpus petition, which is considered a civil filing, the rule could come into play, Rumel says.

"However, when a criminal defendant is no longer in custody and their period of probation or parole has expired, a petition for habeas corpus cannot be used to challenge possible legal errors that led to the defendant's conviction and incarceration," Rumel says.

Even when that specific civil rule is applied, merely showing that there were errors, such as a judge not allowing evidence to be admitted, likely wouldn't be enough to get a void judgment, which is a fairly extraordinary remedy, Rumel says.

"It's gotta be really egregious or really extraordinary circumstances in order to set aside a judgment," Rumel says.

Unsurprisingly, Hunter strongly disagrees with those opinions and feels he's provided plenty of evidence to show that his conviction should be thrown out.

Hunter says he was able to overcome the civil rule barrier that Rumel mentioned when District Judge Susie Jensen ruled on his 2023 case in July last year. She denied his petition because it was his second request under that part of the civil rules, but didn't mention any issue with the rule being used in a criminal case.

Hunter had already dismissed the first request under that civil rule (his 2022 appeal) by the time of Jensen's order, and he thinks his 2023 request should be heard on the merits.

"Nobody has wanted to give me an oral argument to just put this to bed," Hunter says.

He has appealed Jensen's decision.

PERSISTENCE

Regardless of their difference in recalling what happened in 2018, Hagerty says she thinks that Hunter got a bad deal. She says she saw how the case consumed his life."I do feel for him," Hagerty says. "He was treated horribly unfairly."

She says not only did the prosecutor's office and the state "block us in every possible way," while she was seeking evidence, but she thought Hunter's 10-year prison sentence was outsized.

"I felt like that was an extraordinarily hard sentence," Hagerty says. "It's marijuana. It's not meth. Why was he treated so harshly all the way through?"

For now, Hunter continues to be fixated on his void judgment case, which he still hopes an attorney might take up on his behalf.

He says if he can get a court to throw out his conviction, agreeing that his due process rights were violated, his plan would be to sue for the time he lost.

"They would owe me for the 15 years he assigned me with no authority to do it," Hunter says. "All I'm after is the truth."

Still, he's free to leave Kootenai County if he wants. What's next if things don't go his way?

"Well if I had a void judgment it can be ruled at any time," Hunter says.

But what would you like to do with your time, other than be in a courtroom?

"OK, I would like to show, like we did in my federal case, my original case, the evidence I filed in the federal case shows what they did," Hunter says. "About the perjured testimony for probable cause and using all the evidence I show. And even me making an affidavit of what the DVD would have showed..."

Seriously though, outside of the case, when everything's done, what would you like to do, Wylie?

"OK, maybe I am a little bit messed up from all the lock-and-block of prison, knowing what happened to me," Hunter says. "I would want to have my void judgment motion heard, along with the other, for the Supreme Court to see the perjured testimony and everything for probable cause. ... And then I want them to either give me a new hearing, not using perjured testimony, and voiding my judgment..."

He continues listing off the legal arguments that consume his daily efforts, not yet able to think about a future when his past will no longer be so present. ♦