With the global economy on the precipice of a contrived financial disaster, Democratic President Joe Biden and Republican Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy succeeded in negotiating a deal to raise the nation's debt ceiling. Moderates in both parties explained that neither side had gotten their way in the tortuous negotiations, which they argued was the hallmark of a fair deal.

The agreement, however, needed to pass votes in both the House and Senate before landing on Biden's desk. And both the Democratic progressive caucus and the Republican "Freedom" caucus opposed the bill. For those on the left, the deal's budget cuts will harm the most vulnerable Americans; for those on the right, the very idea of government debt is anathema, and no cuts could ever be deep enough. Thankfully, the House passed the measure in a bipartisan vote that nullified opposition from both the left and the right. But each time that politicians flirt with economic Armageddon in pursuit of their narrow partisan interests, we edge closer to the abyss.

Arguments over government debt are as old as party politics in U.S. history. Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson fought over the national debt during the 1790s as the nascent Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties began to coalesce around different visions for the future of the American Republic.

For Hamilton, the first secretary of the U.S. Treasury Department, the national debt would serve as an engine of American economic development. Independence had cost the United States dearly in both blood and treasure. The inability of the Confederation Congress — denied the power of taxation — to service the national debt had convinced politicians in the 1780s of the need to frame a new constitution to create a more powerful central government.

In 1789, President George Washington charged Hamilton with developing a plan to manage the United States' wartime debts (that amounted to around $50 million, about $82 billion in today's money, but with a U.S. population of just under 4 million people to pay for it). While most politicians agreed that the government must maintain its credit with foreign lenders, the government owed most of its wartime debt to private U.S. citizens. Speculators had bought up many of the original loans at bargain basement prices, and many politicians opposed paying them off at face value. Hamilton, however, argued that the national government needed to make nice with these entrepreneurs, who would help to finance the future rise of U.S. manufacturing and the banking industry.

Hamilton's financial schemes reflected his commitment to the economic development of the United States into a banking and industrial powerhouse. He believed that the American Republic possessed resources that could transform the country into an economic juggernaut that would soon dwarf their erstwhile colonial master, Great Britain. Hamilton was convinced that this ambition could only be realized through the centralized planning of a strong national government. Consequently, he proposed that the U.S. government should assume the states' wartime debts to concentrate economic power in the hands of the national government.

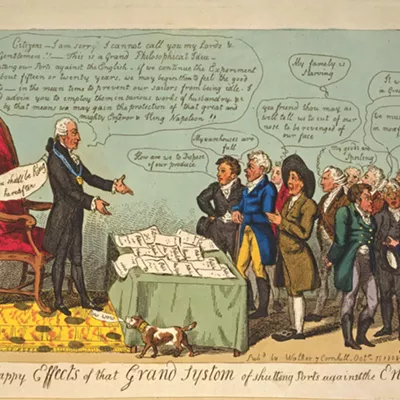

Thomas Jefferson, along with his protege James Madison, opposed Hamilton's financial plans because they entertained a very different vision of U.S. economic and political development. Far from seeking to emulate Britain's manufacturing and banking industries, Jefferson and Madison believed that the United States should avoid them at all costs. They believed that manufacturing threatened republican virtue — the ability of citizens to protect liberty through their political independence — by creating a class of dependent wage laborers. Manufacturing would concentrate power in the hands of a few, while undermining the ability of ordinary citizens to act as a check on the political corruption of their paymasters so long as they depended on them for their wages.

Jefferson and Madison embraced an agrarian vision for the future of the American Republic. They were not opposed to commerce. Indeed, the two Virginians believed that the commercial trade in agricultural commodities was essential to the survival of the Union by creating ties of mutual interest among the different states. But they believed that commercial agriculture was consistent with republican virtue because it nourished the economic and political independence of citizen-farmers, who would sniff out political corruption in government.

The fight over the debt ceiling has become a grimly predictable fixture of political partisanship.

Despite the deep ideological chasm that divided U.S. politics in the 1790s, Hamilton and Jefferson struck a deal. Jefferson's supporters would acquiesce to Hamilton's plans for the U.S. government to assume the state debts in return for Hamilton agreeing to locate the new national capital city in the South, away from the financial centers of Philadelphia and New York. At no point in these negotiations did either side entertain the idea that the U.S. government would default on the payment of its debts.

The fight over the debt ceiling has become a grimly predictable fixture of political partisanship whenever a Democrat is in the White House and the GOP controls the House. Wheeling and dealing has always been part of the rough and tumble of party politics. Still, ideological polarization is no excuse for irresponsible behavior. While Hamilton and Jefferson despised one another personally and politically, both recognized that there had to be limits to political behavior if their experiment in republican government was to endure. Politicians must take government default off the table. If they don't, it is only a matter of time before this irresponsible financial brinkmanship will lead to mutually assured destruction. ♦

Lawrence B.A. Hatter is an award-winning author and associate professor of early American history at Washington State University. These views are his own and do not reflect those of WSU.