This winter, an unusual thing happened in the Pacific Northwest. It’s typical to see temperatures drop into the single digits or lower during the coldest part of the season, but despite the fact that natural gas provides much of the home-heating in the region, the fuel doesn’t usually spike in price for very long.

But after an explosion in October on part of the Enbridge pipeline, which carries much of the region’s natural gas from northern British Columbia down the Interstate 5 corridor and beyond, gas supplies to the PNW were curtailed. When the demand was high with lower supply, prices on the market surged.

Where the Enbridge pipeline enters northwest Washington, prices tend to sit around $2 to $3 per million British thermal units, but during a harsh cold snap from February into early March, they spiked to more than $150/mmBtu, according to analysis from the Northwest Energy Coalition. That spike in the natural gas market for heating also impacted the cost of power trading on the electric market.

An Enbridge pipeline explosion earlier this month will reduce natural gas supply between 20 and 50 per cent of normal levels going into the winter https://t.co/tUvvxgNl91

— CBC News (@CBCNews) October 23, 2018

“If you get a couple days of really, really cold weather, the gas market will go up, and the power market will go up, but it’ll all average out. But the interesting thing about February was, it just kept going, and going, and going,” says Fred Heutte, senior policy analyst with the NW Energy Coalition. “Nobody really expected this, it was sort of a perfect storm.”

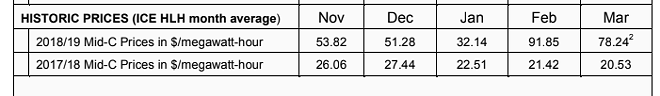

Last winter, power prices for this area ranged from about $21 to $27 per megawatt-hour, but that jumped to a range of about $32 to $92 this November to March, according to information distributed by Bonneville Power Administration.

“The issue was concerning enough that Bonneville Power Administration put out a public request for customers to reduce their consumption, because the other factor that contributed to this, of course, was this took place at a time when hydro runs are very low,” says Sean O’Leary, communications director for the NW Energy Coalition.

The coalition, which promotes renewable energy and energy efficiency with an eye on consumer protection, sees this winter as a potential red flag for the volatility of natural gas, which has largely been considered a stable and affordable source of energy in the Pacific Northwest, O’Leary says. Consumers will soon be paying the price for those higher gas prices on their bills, and while the pipeline rupture in B.C. was a rare stressor on the system, the question to ask after an event like this, he says, is how do you prevent such a spike in the future?

“The good news is, of course, the system worked in that power was not lost,” O’Leary says. “But there is a significant price that we’re going to pay.”

Customers who are served by Cascade Natural Gas, including throughout the Tri-Cities, Moses Lake and other parts of Central Washington, can already expect to see the impacts from those gas prices this month: the company was approved to raise the average residential bill by $4 a month over the next three years to recover an unexpected $48 million it had to spend this winter.

Avista receives much of its gas from Gas Transmission Northwest — another pipeline that goes from Alberta down through the Spokane-Coeur d’Alene area — which wasn’t impacted by the same price spikes. But the overall pinch on the system caused prices to go up throughout the region, says Pat Ehrbar, Avista’s director of regulatory affairs.

“For Avista, because it’s a regional market and we were in that market procuring gas for customers, we were exposed to some of that pricing,” Ehrbar says.

Unlike with Cascade or Puget Sound Energy, which is also looking to recover higher costs, it’s not clear yet whether Avista customers will see any higher or lower bills, as the company tends to go to the Washington State Utilities and Transportation Commission to true-up its actual costs with what it had expected only once a year, Ehrbar explains.

“At this point, we don’t have plans to file anything imminently related to what we’ve seen this winter,” Ehrbar says on Monday, April 8.

One of the concerns for the NW Energy Coalition is that natural gas has earned a reputation as a stable investment to round out the portfolio of utilities’ power options in the hydro-heavy Pacific Northwest, despite the greenhouse gases associated with its use, O’Leary says.

After this winter, O’Leary says the organization of environmental groups and progressive utilities is hoping that the uncertainty in the natural gas system doesn’t promote the building of more gas storage or infrastructure. Instead, he highlights the fact that renewable energy sources aren’t as vulnerable to markets, because they don’t require fuel.

“We don’t want to see more natural gas plants built. The reasons are environmental, but also economic,” O’Leary says. “This is what happens when you rely on power that requires a commodity fuel. Of course, neither wind power, nor solar, nor energy efficiency upgrades require that.”

At least for Avista, however, this winter’s unique events don’t seem to have inspired any push for more natural gas infrastructure yet.

“I don’t know that, in my view, it calls for a substantial increase in storage or other pipeline capacity, given that there isn’t really a need, absent a one-off event,” Ehrbar says.

For Jody Morehouse, Avista’s director of gas supply, the Enbridge pipeline rupture represents a very rare event.

“The track record for natural gas is excellent,” Morehouse says. “Because we’ve had one incident, does that make me concerned? I would say no, it doesn’t. I’d say if anything it points to the fact that overall, the natural gas system is very reliable.”

Still, Avista was impacted when a gas storage facility it shares with other utilities on the west side of the state had largely been drawn down by the time the coldest weather of the season hit. At that time, the company did ask some of its largest industrial customers to voluntarily switch to another source of power if they could, or reduce their use for that timeframe, Morehouse says.

The winter also sparked use of a mutual agreement Avista has with other regional utilities, who come together during emergency events to make sure the system continues working, Morehouse says.

“One way we plan for those kind of events is to quickly call that team of people together and talk through how can we manage that regionally,” Morehouse says. “We all have plans for how much storage, how much we take from this pipeline or that pipeline, but now regionally we are also talking about if there are ways we can do that in a broader way. That’s a fairly new thing for us that came to light with this emergency that happened, that we should be asking some bigger questions.”