More than half of the city would be off limits to camping under a proposed ban going before voters next month.

Both the people promoting Spokane's Proposition 1 — which would ban camping within 1,000 feet of schools, parks, playgrounds and child care facilities — and those fighting against it say they don't want homeless encampments near places meant for children.

But they differ in what they believe will happen if city voters approve the ballot initiative, which asks whether Spokane city code should be amended to expand the existing camping ban.

Proponents say an expanded ban is necessary to break up Camp Hope-style encampments, arguing that police likely wouldn't enforce the ban everywhere it applies, but could better enforce problem camps. Opponents say that even the threat of enforcement will likely push people to camp deeper in neighborhoods and on the outskirts of city limits, farther from services they need.

Under current city code, camping is already banned on public property, including conservation lands, along the Spokane River and Latah Creek and their tributaries, as well as under or near the railroad viaducts in downtown and within three blocks of congregate shelters.

Among those running for office, Mayor Nadine Woodward, City Council president candidate Kim Plese, and City Council candidates Katey Treloar, Earl Moore and incumbent Michael Cathcart support Prop 1. Mayoral candidate Lisa Brown, City Council president candidate (and current council member) Betsy Wilkerson, and City Council candidates Paul Dillon, Kitty Klitzke and Lindsey Shaw oppose Prop 1.

IMPACT IF PASSED

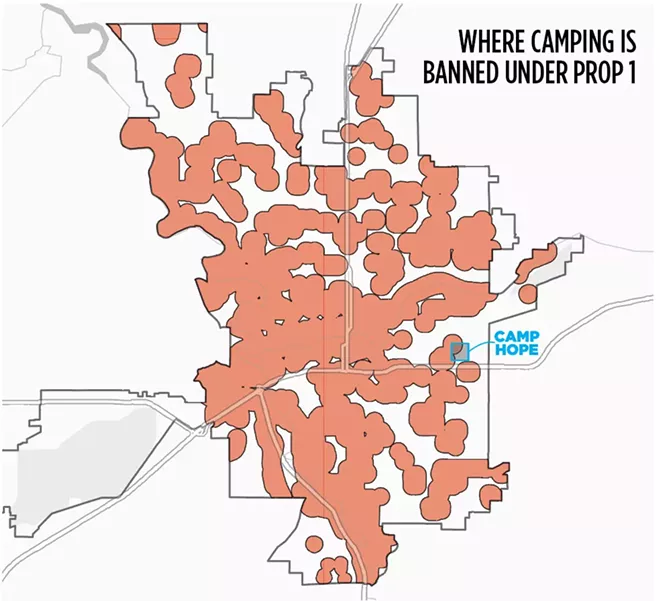

After hearing about Prop 1, Eastern Washington University Professor Robert Sauders mapped out the areas that would be affected. He says the 1,000-foot restriction around each location particularly piqued his interest."The GIS nerd in me said, 'I know that's a substantial portion of the city when you have that criteria,'" says Sauders, who teaches geography and anthropology. "This probably sounds reasonable to folks, but it's a lot of the city."

His map shows that, if enacted, the measure would ban camping in about 55% to 64% of the city, depending on whether you include the land at Spokane International Airport, which makes up about 9% of the city's area.

"We as a city have positioned resources in a centralized area downtown that's effectively going to be a no camping zone," Sauders says.

If camping is pushed into the areas not covered by the ban, more visible encampments could pop up in parts of Rockwood, Cliff-Cannon, Lincoln Heights, Southgate, Grandview/Thorpe and Latah Valley, East Central, Northwest, and Indian Trail neighborhoods.

For what it's worth, only part of the block that was home to Camp Hope would fall within the 1,000-foot boundary from a school that the ban calls for.

ARGUMENT FOR

Clean and Safe Spokane, the political action committee promoting Prop 1, argues that the ban is needed because homeless encampments "endanger the lives of our children." The group argues the camping ban would protect neighborhoods.

"This is a step in the right direction to help reduce the dangerous, dirty, and disruptive behavior inherent in homeless encampments around areas where our children learn, play, and grow," reads the voters' pamphlet argument "for" Prop 1 that was prepared by attorney Brian Hansen — who helped put the measure on the ballot — and Spokane City Council member Jonathan Bingle.

Camp Hope, in the East Central neighborhood, grew to more than 600 people at its peak last year, raising concerns about crime, refuse and dangerous behavior. After seeing the impacts, the backers of Prop 1 looked to anti-camping policies in other cities and crafted the initiative to be compliant with Martin v. Boise. In that case, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals determined that cities can't enforce camping bans if there's a lack of shelter beds available, because it's "cruel and unusual" for governments to make it illegal to simply exist outside if no indoor options are offered.

The Martin decision prevents cities from banning all camping when there's no shelter space, but it doesn't prevent cities from banning it in specific areas, says Mark Lamb, the Seattle attorney who is representing the proponents of Proposition 1. Hansen and John Estey, the chair of Clean and Safe Spokane, referred all questions to Lamb.

"It gives police in Spokane another tool in their toolbox when you have problematic encampments like Camp Hope," Lamb says of Prop 1. "It's a tool to say, 'There are places that are not appropriate to have camping within the city limits.'"

A legal challenge to the measure will be heard on Oct. 25 before the state Court of Appeals, but that challenge has to do with whether voters have the legal authority to change city code via initiative.

If voters approve the measure, the legal question about whether the ban would be enforceable under Martin could be brought to court. Progressive cities such as Los Angeles and Portland have banned camping within 500 feet and 250 feet of similar sensitive places, Lamb says.

"If we are challenged we'd be in the company of cities like Los Angeles and Portland," Lamb says.

ARGUMENT AGAINST

Meanwhile, people who work in eviction prevention, homeless services and more argue that the ban won't fix the issues that result in homelessness, or eliminate encampments, which would likely move to other areas. Ironically, the opponents argue, the measure could actually create large encampments.

"The unintended consequence of limiting space where people can exist means that encampments that are not prohibited by Proposition 1 will look more like Camp Hope because of the limited space where they will be allowed," according to the "against" statement that was submitted to the Spokane County Auditor's Office about an hour too late to make it into the voters' pamphlet.

The statement, prepared by three people including Terri Anderson, the statewide policy director for the Tenants Union of Washington State, argues that rent increases, evictions and severely low vacancy rates are actually driving homelessness.

"We don't have a homelessness problem, we have a housing crisis," Anderson says. "They'll just be squished into smaller spaces that are probably more visible, and probably impacting neighborhoods. In many ways it's probably going to make it worse."

Julie Garcia, founder of Jewels Helping Hands, a homeless service provider that worked with other nonprofits to help those at Camp Hope, also contributed to the "against" statement.

"We as a community all agree that homeless encampments should not be near our schools or playgrounds or parks. But if we tell people where they can't go, we have to tell them where to go," Garcia says. "We are slowly and systematically removing people's rights to exist."

Garcia says that Jewels Helping Hands has already been finding more people in north Spokane in need of resources, as many started camping in the area of the Division Street "Y" and north into the county after Camp Hope closed. She says the community needs to invest in more wraparound housing services or sweeping encampments won't fix anything.

"All it does is alienate those folks farther and farther from those services that help them exit homelessness," Garcia says. "We continue to operate under the idea that if we wish them away, they somehow disappear. That is not the case. They're going to move to where they're allowed to be, and unfortunately that's going to be into neighborhoods that are unprepared to care for them." ♦