In the early morning of June 10, 2015, Dennis Platz woke up to go open the gate to his Colbert property and let in his neighbor, Dan Carver, who planned to borrow a field sprayer.

Platz walked out of his camper trailer with his dog around 5 am and started walking toward the gate, but his dog noticed something under the porch of his house: a figure dressed all in black.

Carver would tell police that the figure came out from under the porch with a gun and shot Platz in the thigh. They fired toward Carver — he tells police he could smell gunpowder and feel the pressure wave of a bullet that missed him — and then stood over Platz, now spread out on the ground, and fired at his head, narrowly missing.

Doctors would find bullet fragments in Platz's ear at the hospital, and police later found a bullet buried inches in the dirt near where his head would've been as he lay on the ground.

The person then ran off as Carver and Platz's wife at the time, Gail, tended to his wounds and called 911.

Jennifer Anderson, Gail's adult daughter, was arrested nearby on a country road where, court documents say, police found a .40-caliber Glock handgun on the ground nearby with an empty magazine and another full magazine. She was dressed in all black, and a car she'd borrowed from a friend the night before was later found parked in the area.

Anderson refused to speak to police without an attorney. At the request of jail staff, her mental health was questioned, ultimately sparking a years-long process of evaluations and hospitalizations.

Anderson and Platz had been involved in another incident earlier that year. Anderson had stabbed Platz several times, later telling police he attacked and choked her. After he was treated at the hospital, he was booked into jail on suspicion of domestic violence. But Platz maintained that he was the victim. After Platz's house was shot up that April (no one was injured or arrested in that incident), and after he was physically shot that June, the charges against Platz were dropped.

Anderson was charged with first-degree attempted murder and first-degree assault.

Like many people before her, Anderson encountered unconstitutional months-long delays to get the court-ordered services that are meant to stabilize behavioral-health patients with medication and/or proper medical care.

During multiple forensic evaluations logged in court documents as part of the case, Anderson told doctors about several delusions, including that Platz was part of a mafia group due to his previous membership in the Teamsters union, that the Illuminati were out to get her, and that she had been kidnapped or forced at gunpoint to go to Platz's house on the day of the shooting. She also described various traumatic events throughout her life.

Complicating matters, charges were dropped in 2017 when her mental health seemed poor, then refiled in 2018, prompting even more evaluations at Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake.

Since the June 2015 shooting, more than 2,254 days have gone by without a resolution to the case, for either Anderson or Platz.

"It's wrong for both him and I to have to live under this thing that's ongoing," Anderson tells the Inlander. "I feel it's a great injustice. I feel like mental health patients are invisible and that people think that we don't matter."

In a March 2019 forensic evaluation, the doctor who interviewed Anderson notes that there's good evidence she may have been suffering from psychosis at the time of the shooting and over the course of the year before that. But she also was noted to have responded well to treatment in the intervening years and appeared competent and able to understand her case and support her own defense by that point. The same doctor noted that Anderson appeared to have no issues at all for several months after her charges were dropped, and other doctors had previously questioned whether she was exaggerating some symptoms.

"Ms. Anderson is truly stuck between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, she is potentially facing a trial that she stated she doesn't think she can win," forensic psychologist C. O'Donnell writes in the March 2019 evaluation. "On the other hand, she is potentially facing an extended hospitalization, which she also doesn't want."

But there isn't a scenario in which neither is likely, the doctor notes.

"She can't be so ill that she's unable to be restored to competency on an attempted murder charge but then be so healthy that she doesn't need psychiatric treatment," O'Donnell writes. "Thus, I will defer my opinion regarding whether Ms. Anderson suffers from a mental disease to the trier of fact."

TRUEBLOOD

As chance would have it, it's also been six years since Washington state got a wake-up call: A federal court ruled the state was taking far too long to admit criminal defendants into state hospitals for mental health evaluations and treatment. If things didn't change, the state would be fined for contempt.In 2014, public defender Cassie Cordell Trueblood, along with other public defenders and mental health advocates, sued the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services and its two major hospitals on behalf of more than 100 defendants statewide who'd been languishing in jail while waiting weeks or months without treatment.

When someone's mental health during and after an alleged crime comes into question, the state has to evaluate them for mental illness and ultimately decide whether they are able to assist in their own defense and are competent to stand trial. If they're not competent, their case can be paused while they are treated at a state facility, where they may be "restored" to a point where they can understand the charges against them, get returned to jail or the community, and eventually go to trial.

For years, advocates had pointed out that jails rarely, if ever, offer the type of specialized care these types of defendants need, and folks may get worse while waiting in what's often some form of isolation. In some cases people were spending more time waiting to be admitted for pretrial treatment than they would have even been sentenced to serve for their alleged crime.

After a civil trial in early 2015, a federal judge held that "jails are not suitable places for the mentally ill to be warehoused while they wait for services."

"Jails are not hospitals, they are not designed as therapeutic environments, and they are not equipped to manage mental illness or keep those with mental illness from being victimized by the general population of inmates," the April 2, 2015, ruling from U.S. District Judge Marsha Pechman states.

The court ruled that the state needs to complete initial in-jail mental health evaluations within 14 days. Anyone whose mental competency is questioned after that evaluation needs to be admitted to a state facility within seven days if a court orders further evaluation and treatment.

But several years — and more than $85 million in contempt fines — later, the state still has yet to fix those waiting periods.

Significantly, Western and Eastern State Hospitals aren't admitting people within anything close to a single week after receiving a court order to evaluate or restore someone.

How bad are they failing? During six different months in 2020, zero percent of cases were admitted to Eastern State within the court-ordered seven days for inpatient evaluations. At most, the facility hit 50 percent success during one month when they timely admitted one of only two individuals ordered there that month.

"We continue to fail the most vulnerable parts of the legal system," says Kari Reardon, who served as a public defender in Spokane County for nearly 24 years and is now director of the Cowlitz County Public Defender's Office. "These are people that desperately need help, and they're not receiving it in a timely manner."

A 2018 settlement in the Trueblood case has helped fund community mental health investments that first came online in 2019 and 2020, and Spokane is among the first areas to see the products of those efforts. But it could take years to see if any of those mental health programs reduce the amount of time people are actually spending in jail, or whether they're able to ultimately prevent people from entering the criminal justice system in the first place.

Until then, both people who are struggling with behavioral health issues and victims who may get caught in the crossfire during a state of crisis continue waiting through a system that's slow moving and even slower to change.

FINES ARE NOT PERFECT FIXES

Anderson's case was one of 25 Spokane cases around 2014 and 2015 that landed DSHS with nearly $200,000 in fines for taking too long to conduct inpatient services.In October 2015, Anderson's public defender at the time, Reardon, asked Spokane County Superior Court to find DSHS in contempt for failing to admit her under the newly enforced Trueblood standards that require admission within seven days of a court order for competency services.

At the time, DSHS said it had 42 people waiting to receive inpatient competency services at Eastern State.

Anderson was finally admitted to Eastern for the first time in December 2015, 95 days after the court said she should be and a full six months after the shooting.

Her case and the others ultimately made it to the Washington Supreme Court, which found in early 2019 that Spokane's Superior Court could fine DSHS $200 per day if it failed to meet admission deadlines.

In Anderson's case alone, DSHS was ordered to pay $13,200 in contempt money, and overall the 25 Spokane cases smacked the state agency with a $197,600 fine. That money was paid to Spokane County in August 2019 to help fund the jail's limited mental health services.

"Spokane County Jail has the unique situation that there's an entire mental health unit that does what they can to assist people," Reardon says. "But they're not a hospital, and they cannot provide a hospital level of care."

One of the hard things for Trueblood cases is that even when fines are ordered to fund services that would prevent other people from experiencing the same delays, that doesn't often change anything for that person's case, explains Kimberly Mosolf, director of the treatment facilities program for Disability Rights Washington.

"Trueblood does not get them individual fines," Mosolf says. "[Fines] go to these programs that are hopefully going to keep other people from being in your situation, but I don't know that I'd want to hear that as someone stuck in jail for two months."

In 2018, Disability Rights Washington, on behalf of behavioral health defendants accused of crimes who are now known as "Trueblood class members," settled with DSHS. There was, in part, a recognition that at the same time the state was working to speed up the process, court orders for inpatient services were massively increasing. It's possible that's partly due to better access to health care under the Affordable Care Act, which may have helped identify more behavioral health patients. DSHS went from figuring out how to deal with 978 inpatient orders in 2013 to as many as 1,831 in 2019.

It became clear that simply investing in more beds and staff at hospitals wasn't going to adequately address the issues, Mosolf says.

"The state essentially said, 'We cannot build our way out of this problem,'" Mosolf says. "The number of folks being funneled into the criminal legal system with behavioral health issues was skyrocketing and continues to grow. There was a mutually recognized opinion that we needed to do something to try to stem the tide and turn that faucet off if we were going to make any longer term difference."

Under the settlement, the state hired more forensic investigators to conduct in-jail interviews within the required 14 days, and brought on new forensic navigators to help guide people to services. The state would also help pay for new outpatient facilities in communities around the state.

"We don't have a well-funded mental health outpatient service system, and our crisis system has a lot of holes in it," Mosolf says. "A lot of folks are unfortunately reaching crisis [level], and then we're sending law enforcement, and they're not mental health professionals."

Since 2019, Trueblood-funded grants have gone through Disability Rights Washington to multiple organizations to fund everything from social workers who can tag along with police officers on behavioral health calls to crisis stabilization beds for those in mental health or substance use crises.

They'll test whether hospitalizations and jail visits can be reduced, and whether people with behavioral health issues can be better helped before they hit the point where they are in crisis.

"The number of folks being funneled into the criminal legal system with behavioral health issues was skyrocketing and continues to grow."

NORTHEAST WASHINGTON AMONG FIRST INVESTMENT AREAS

The Spokane area (including Adams, Lincoln, Ferry, Stevens, Pend Oreille and Spokane counties) is one of the first three areas targeted for investment under the 2018 settlement. The other two areas getting the first investments include Pierce County and Southwest Washington (Clark, Skamania and Klickitat counties).By October, Pioneer Human Services, the city of Spokane and Spokane County plan to open a new crisis stabilization center, the newest of several community investments.

Construction on the new Spokane Regional Stabilization Center is just wrapping up this month. The facility will include 16 mental health crisis stabilization beds, 14 withdrawal management beds, and 16 co-occurring residential treatment beds, says Dan Sigler, Spokane regional director for Pioneer.

"A lot of times during the treatment process, people may have to go from one site to another due to other needs," Sigler says. "To do this on one campus really minimizes the interruptions for people in crisis."

In particular, the residential beds may come in handy for people who would otherwise be stabilized over the course of three to five days or so, but then returned to a situation where they don't have anywhere to live, he says. The residential beds can help bridge the gap for a few weeks, providing stability while their care team figures out a housing situation and/or health care treatment facility for them to move into.

For about two years now, one of the most active, on-the-ground solutions has been the co-responder program. Several Spokane Police Department officers and Spokane County Sheriff's Office deputies are deployed with mental health or substance use experts from Frontier Behavioral Health, who can help respond to calls and direct people to services in the moment they're experiencing a crisis.

From 2020 to 2021, 76 percent of the team's contacts with 3,915 different people resulted in something other than jail or a hospital visit.

The team has also helped accelerate the handoff to services. In the past, officers might have followed up a day or more later with someone to get them services, but by that point they may have changed their mind. Now the team can drop someone off for housing or treatment right away, explains Spokane Police Sgt. Jay Kernkamp, the supervisor of the program.

Currently co-responder teams work Monday through Friday, 7 am to 10 pm, and the group is looking to expand from five co-deployed teams to seven, with Trueblood funding passed through a Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs contract.

Significantly, of the nearly 4,000 people contacted by co-responder teams in the last two years, only 33 were arrested, Kernkamp notes. More than 700 were detained under civil commitment laws, and the team took on more than 2,500 hours of calls that would've otherwise been handled by patrol officers.

The team has been able to build a rapport with people who might contact 911 repeatedly or have multiple contacts with officers.

"What we've found is that by continually following up with them after that state of crisis — making sure they're on their medication, getting food, getting housing, getting clothing, all the essentials they need to stay at a baseline behavior — we're able to prevent them from decompensating and going into a state of crisis again," Kernkamp says.

The teams will also be able to take people to the new crisis stabilization center once that's up and running.

Several other programs intended to address Trueblood class members also came online in the last year or so.

In March 2020, Frontier Behavioral Health started offering its Forensic HARPS and Forensic PATH programs. The services are intended to get people into more stable housing situations (sometimes that means motel rooms or partner agency-owned apartments) and to connect people with stable treatment within the community.

In July 2020, Frontier also started offering outpatient competency restoration, under which the state has agreed to let some people facing low-level criminal charges receive their competency services while out of custody.

Most recently, Frontier just received a $6.8 million grant, along with Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington and Pioneer Human Services, to provide more apartments for behavioral-health patients, including 24 units to be newly built.

"If you don't have housing, it is so much more challenging to just get through a day," says Jan Tokumoto, chief operating officer for Frontier. "That is a huge resource that could make a difference for people."

LONG ROAD AHEAD

Those investments are already creating measurable improvements in the Spokane area.But experts say there's still a long road ahead as communities around the state continue working to come into compliance by admitting people from jail into treatment facilities in a timely manner.

"I continue to be hopeful about the settlement and these programs," Mosolf says. "But for those who are still waiting, it's an incredibly frustrating situation to be in."

In Anderson's case, new trial dates have been set and postponed multiple times this year, partly because she received a new public defender in early 2021 who needs time to catch up.

Anderson, 44, declined to comment on details of her case, noting that she's been advised not to. But she says managing her mental health is the most important thing in her life now.

"You can medicate us mental health patients, that's great, but that is not going to help you fix your processes as far as paranoia or seeing things in a way that the rest of the world might not see them," Anderson says. "Cognitive Behavioral Therapy has really been the most beneficial thing, and that is something that is the last thing that they turned to when it should be one of the first in my opinion."

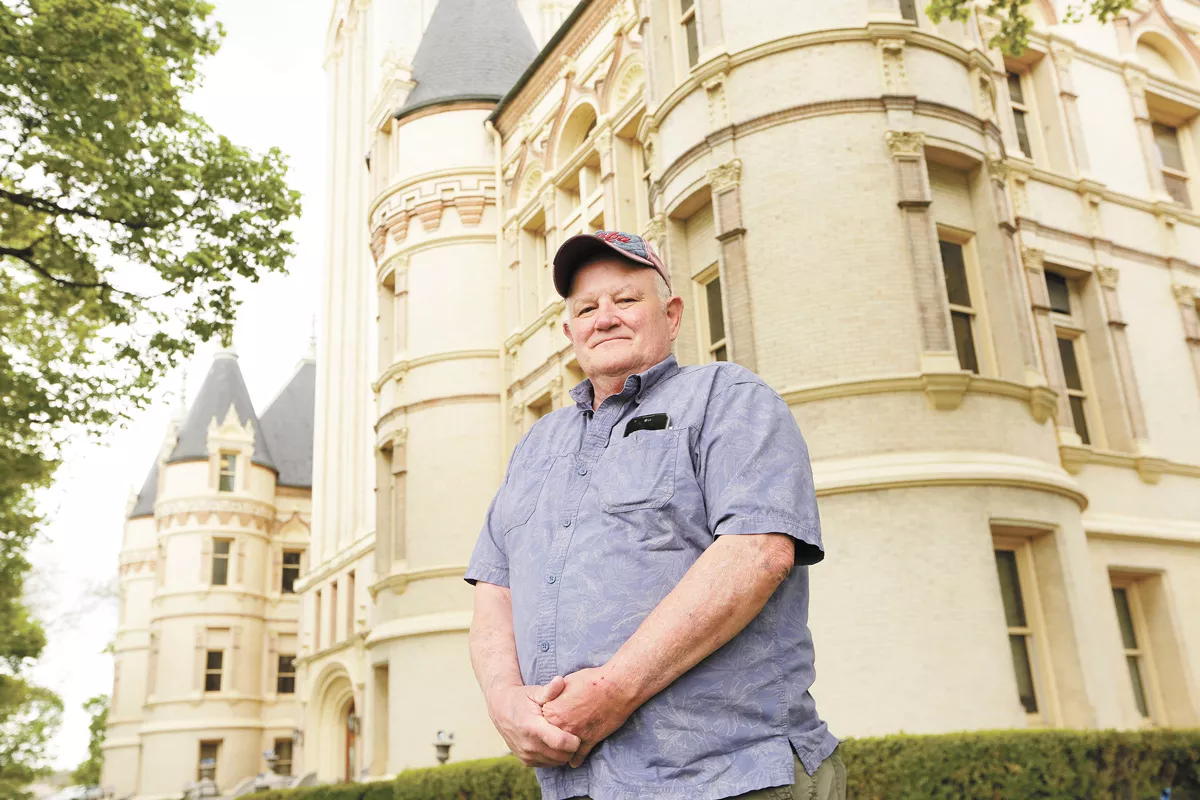

Platz, 69, says he's suffered from PTSD and night terrors after the incidents in 2015 and it's hard to heal and move on while the case lingers. He wants to be able to feel safe in his home and see the justice process play out.

"I want my day in court over all this," Platz says. "They say you need closure. I can't get any closure."

From the time the case started, Anderson hasn't been able to see her four children, who are now in their teens and early twenties. She hopes to see a resolution soon so she can rebuild her life.

"I'm not a monster like they've portrayed me to be," Anderson says. "I would just like everything to be resolved so that I can move forward in my life and he can move forward in his life. You know, this still kind of ties us together, and I would like that untied and just for us both to be able to move on."

In hundreds of other cases statewide, defendants continue to spend unconstitutional wait times in jail. DSHS has fairly successfully addressed in-jail evaluations, but hospital admissions remain an issue.

"I want my day in court over all this. They say you need closure. I can't get any closure."

"DSHS has done a great job of getting more evaluators and getting evaluations done within 14 days and often less," Reardon says. "Where the problem has come in is people are not admitted to the hospital in a timely manner, so they're sitting in jail and getting worse or simply not receiving the treatment they need for a variety of reasons."

Eastern State Hospital is now completing most in-jail evaluations within the required two weeks. At the start of the pandemic, Eastern was close to 90 percent compliance with the two-week window for completing those evaluations.

During the pandemic, that dropped to as low as 58 percent of people getting their in-jail evaluation within 14 days of a court order.

More recently, things have been better, explains Dr. Thomas Kinlen, director of the Office of Forensic Mental Health Services at DSHS, who focuses on Trueblood issues within the agency. For 2021 as a year, Eastern has been able to complete in-jail evaluations within 14 days in about 88 percent of cases, he says.

With the pandemic, many jails had to quickly set up video conferencing services, which actually helped with compliance, Kinlen says.

"One of the reasons we're even that close is the continued ability to do these tele-evaluations, because COVID is still here," Kinlen says.

As for admitting people within seven days who require it, that's another story. At one point last year, the average wait to get into Eastern was 108 days.

"A year ago, it might've taken someone five months to be admitted to Eastern or Western State Hospital," Kinlen says. "Now Eastern State Hospital is under 45 days for everybody, and most individuals tend to be under 10 days waiting to be admitted."

In the meantime, folks in mental health crises aren't likely to get the care they need while waiting in jail, Reardon explains.

"Honestly, unless you are harming yourself, it is extremely unlikely that you will be admitted to a facility within the appropriate time frame," Reardon says.

The state Legislature recently agreed to build a new 350-bed facility at Western State Hospital with the hopes of further reducing wait times for Trueblood class members to receive treatment.

But advocates for those in the criminal justice system say the better investments are likely on the front end, where you can ideally prevent people from entering the system in the first place.

"We like better buildings, but that doesn't solve the problem," Reardon says. "The state has significantly more room for improvement for how we treat those with mental health issues in the legal system. We are failing our most vulnerable." ♦