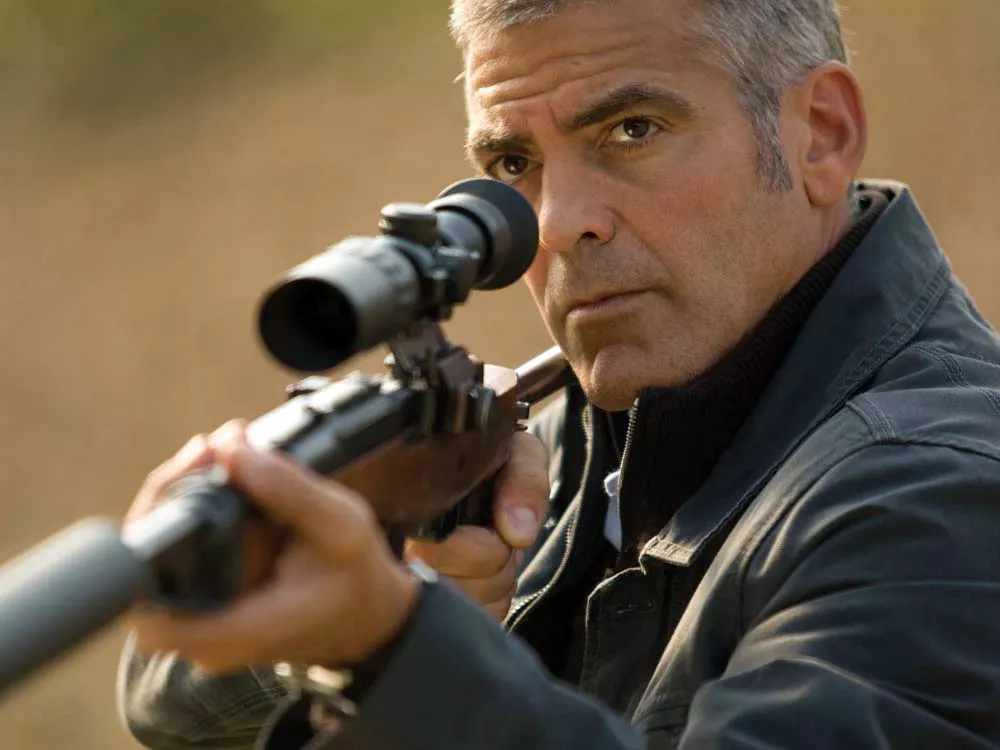

George Clooney is one stressed-out assassin. he winces a lot, rubs his eyes, wears a pained expression. He drives alone at night, moody. he walks through dark and deserted streets, moody. there’s a lot of moodiness in the air.

In The American and films like it, that moodiness and the syrup-slow pace are usually intended to engage viewers psychologically. You’re not supposed to doze off, you’re supposed to be thinking about the moral significance of the hit man’s actions: will he defy his handler, protect the girl, get out of this dehumanizing racket?

In one scene, Clooney has grown suspicious of the gold-hearted hooker he has befriended (the stunning Violante Placido). Must be all the stress. so he takes another drive, enters yet another phone booth, calls his spymaster and argues with him, broods in yet another cafe over yet another cup of espresso.

Padding events like this has a purpose if the events raise questions that require time for rumination. But the dilemmas raised by The American aren’t complex. Should he get out? Yes. Should he build meaningful relationships and stop being so aloof all the time? Yes. Are the bad guys bad? Well, they’re not very good: Director Anton Corbijn fumbles the film’s only two action sequences with eye-rolling implausibility.

To be fair, Corbijn often succeeds in creating tension. The opening sequence in snow-blanketed Sweden is truly startling. When Clooney delivers the high-powered rifle he has built, you can feel the danger he’s in. And in a minimal-dialogue movie that needs a good soundtrack to prop up sagging interest, Herbert Gronemeyer delivers a gloomy, minimalist score full of groaning cellos and blips of electronica.

The American also has its location going for it: the hillside town of Castel del Monte (only 400 real-life residents, preserved in a national park, looking much as it did during the renaissance). Those winding stone stairways make for great chase scenes. They’re like a labyrinth.

That’s it! Clooney’s caught in a maze, he doesn’t know how to get out, the layout of the town is a metaphor for his quandary. Let’s be sure to emphasize that. Let’s emphasize that many, many times. (Rated R)