While on the interview circuit promoting his new film The Irishman, director Martin Scorsese was casually asked a question that would unexpectedly dominate the internet for what seemed like an eternity: A journalist at Empire magazine wondered what he thought of Marvel movies.

"That's not cinema," Scorsese responded. "Honestly, the closest I can think of them — as well made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances — is theme parks. It isn't the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being."

It touched a nerve. Folks in Scorsese's camp thought that he was speaking harsh truths about the state of the industry. Others heard his comments and just saw that Simpsons "Old Man Yells at Cloud" meme. And then the major players in the Marvel Cinematic Universe had to weigh in, from Robert Downey Jr. to Scarlett Johansson to Marvel head honcho Kevin Feige. Their defenses all boiled down to the same fatuous argument: Scorsese's entitled to his opinion, but our movies are popular, so who cares?

It devolved into a nuance-free reductio ad absurdum typical of the Twitter age: You either had to be Team Scorsese or Team Marvel. Scorsese felt the need to further contextualize his remarks with an op-ed in the New York Times, which wisely focused less on the inherent artistic worth of Marvel films than their sheer unavoidability.

"In many places around this country and around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen," he wrote. "Many films today are perfect products manufactured for immediate consumption. Many of them are well made by teams of talented individuals. All the same, they lack something essential to cinema: the unifying vision of an individual artist."

Basically, it's always been hard to get risky, audacious, vision-driven films financed by major studios. But the trend toward a specific kind of large-scale storytelling — expensive action spectacles set within sprawling universes — has made it exponentially harder.

Marvel movies, as a subgenre unto themselves, have become a monolithic symbol for the way major films are made and marketed. They're well-constructed, studio-mandated objects, released with the expediency and regularity of Funko Pop! figurines — collect all 23. Scorsese, meanwhile, is emblematic of another type of filmmaking entirely, a type that will take one more step toward extinction when his career comes to a close.

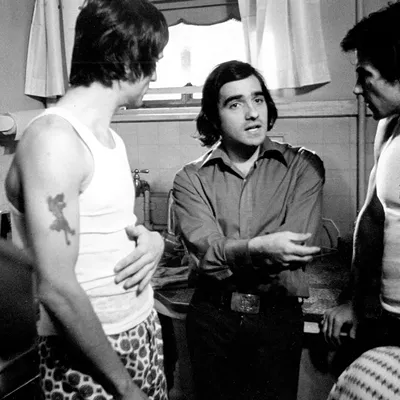

If Martin Scorsese isn't the greatest working American director, there aren't many others out there who would be reasonably deserving of that title. As with so many other filmmakers of his generation, he got his start making cheap exploitation movies for prolific producer Roger Corman, but he really broke out with his acclaimed 1973 feature Mean Streets, a gritty and harrowing drama inspired by his time growing up in the hardscrabble back alleys of Little Italy.

That film got Scorsese critical attention, and it established a number of his most recognizable trademarks — vivid New York settings, restless camerawork, fragmentary editing (often courtesy of the inimitable Thelma Schoonmaker), jukebox soundtracks, protagonists who didn't always do the right thing.

More so than any other filmmaker of his era, Scorsese successfully married the stylistic experimentation of arthouse cinema with the classical, character-driven storytelling of old-school Hollywood. His films were frank in their language, often stomach-churning in their violence, and yet also deeply moralistic (no doubt a byproduct of his rigid Catholic upbringing). His bad guys don't always pay for their crimes with their lives, but in a Scorsese film, having to contend with your sins is a fate worse than death.

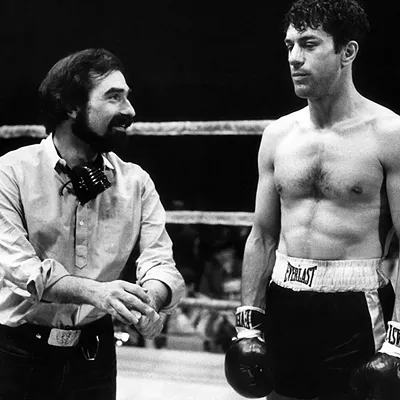

Scorsese is most commonly associated with his feverishly styled crime epics — GoodFellas, Casino, The Departed, The Wolf of Wall Street and now The Irishman — and has even been knocked for making the same movie too many times. But criticizing him for repetition is to be ignorant of his varied filmography. He has made poignant, frightening studies of broken men (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The King of Comedy, The Aviator); slice-of-life dramas (Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, The Color of Money); thoughtful religious meditations (The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun, Silence) and lurid genre exercises (Cape Fear, Shutter Island). He explored 19th century social mores in The Age of Innocence, and paid tribute to Technicolor musicals in New York, New York. The high strung urban comedy of After Hours is nothing like the gentle family-friendly fantasy of Hugo.

And that's just his narrative features. He has also helmed documentaries and live concert films, including the groundbreaking The Last Waltz; a visual essay about his own personal journey through films; an exploration of his own Italian-American heritage called My Voyage to Italy.

Scorsese's artistic influence is inescapable, and can be seen in movies as wide ranging as Boogie Nights, Catch Me If You Can, American Hustle and The Big Short. Surely, The Sopranos, with its uneasy blend of mordant humor and out-of-nowhere violence, owes a debt to Scorsese's body of work. Just recently, Todd Phillips' Joker became the highest grossing R-rated film of all time, and it's so beholden to Scorsese's ouvre — particularly Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy — that it often plays like a tribute act.

That influence extends to his behind-the-scenes work. He founded two nonprofit organizations — the Film Foundation and the World Cinema Project — that are dedicated to preserving and restoring films in danger of being lost. He has also helped finance films by Spike Lee, Stephen Frears, Kenneth Lonergan and Ben Wheatley, and he's credited as an executive producer on a number of films from this year — Joanna Hogg's widely acclaimed The Souvenir, Kent Jones' terrific and underseen Diane, and Josh and Benny Safdie's upcoming comic thriller Uncut Gems, which tips its hat to the paranoia and menace of vintage Scorsese.

One could argue that, despite a career that reaches back to the late '60s, Scorsese has never been more relevant than he is right now.

When Scorsese criticizes the Marvel model, he is, of course, coming from a place of tremendous privilege.

In order to fund his latest crime epic The Irishman, he turned to Netflix, a platform that has arguably altered the cinematic landscape more completely than Marvel. Going the Netflix route means that most people won't see the film the way its maker intended — with a packed crowd in a movie theater. But the streaming service's famously reckless financiers also gifted Scorsese one of the largest budgets of his career (a whopping $160 million), a five-month shooting schedule and total artistic freedom.

Very few filmmakers, even those of Scorsese's caliber, could ever dream of a deal that sweet. Because for all the talk of artistic merit and integrity, every movie is a business transaction. It's all about how a filmmaker expresses their own vision within the parameters of that transaction.

Even so, Scorsese is using his clout for good. Regardless of your position on his "Marvel movies aren't cinema" stance — and I'm not even sure I totally agree with him — he has initiated a vital conversation about studio politics, and about the importance of diversifying theatrical offerings: Small, thoughtful, grown-up films can and should coexist with all-ages blockbusters filled with explosions and feats of strength.

The arguments have also largely overlooked the tremendous achievements of a 50-year career, and of Scorsese's encyclopedic knowledge of all things film; watching the Twitter commentariat explain the inner workings of the studio system to Martin f—-in' Scorsese is pretty hilarious. And besides, why does Marvel, one of the mightiest juggernauts in the history of entertainment, need defending from anyone? If this debate were an '80s movie, it'd be like the nerds in the A.V. club defending the honor of the most popular kid in school.

Still, there's a reason some of the richest people in Hollywood are taking one 77-year-old's opinions personally. As a preeminent film artist, what he says matters to other film artists, even if it won't make a dent in Marvel's box office receipts. Scorsese's comments come not from a place of moral superiority but defensiveness: He loves cinema more than anything — and maybe more than anyone — and he's feeling protective of an art form that he no longer recognizes.

At a time when big-budget filmmaking is prioritizing market saturation above creative audacity, his voice is all the more valuable. ♦

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nathan Weinbender is the Inlander's film and music editor. He is also a film critic for Spokane Public Radio, where he has co-hosted the weekly show Movies 101 since 2011. He has been a diehard Scorsese fan since seeing Taxi Driver and GoodFellas in high school, and one day he'll actually get around to watching Kundun.