As Lisa Silvestri started researching how American troops use social media, it didn't take long before she realized that like almost everyone else, they enjoyed using Facebook.

She talked to one soldier, a driver of armed trucks for the Marine Corps in Afghanistan, who was excited because he thought social media would let him talk to his family and friends and make him feel a little less homesick.

But that soldier soon got tired of social media. He wanted to focus on where he was at the moment — a war zone — so he could get back home safely. He started using Facebook less, but that caused his family and friends to wonder why he was ignoring them. His girlfriend of three years broke up with him. In Afghanistan, he had to worry about problems back home. He felt like he had "one foot over there and one foot here."

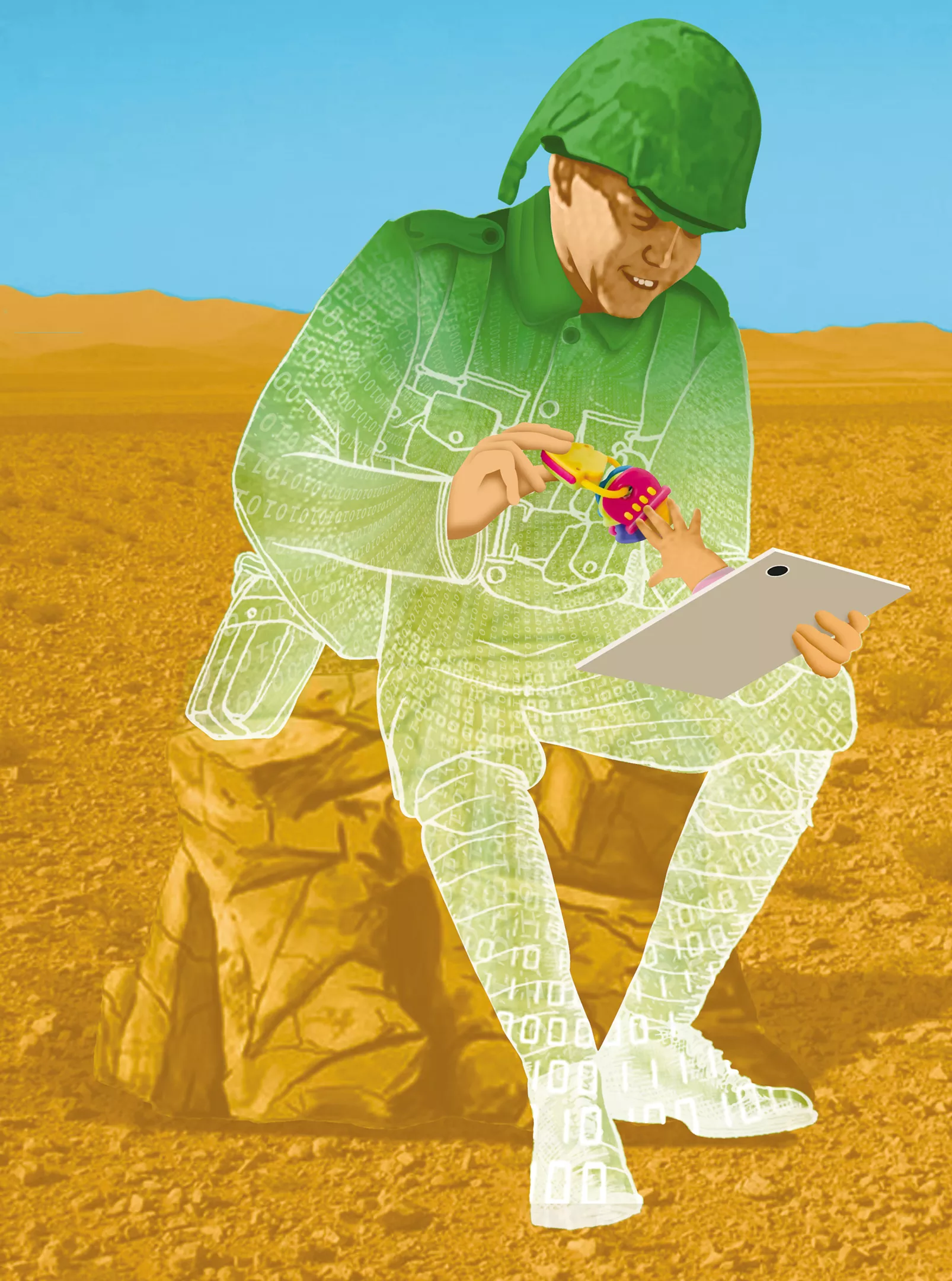

Silvestri, in her 2015 book Friended at the Front: Social Media in the American War Zone, writes that this kind of experience is not unique for modern-day troops. Silvestri, currently an assistant professor in the communication studies department at Gonzaga University, spent years interviewing troops fresh from deployment, starting in 2010. What she found is that soldiers use social media similar to the way it's used at home, but that can have a different impact in the context of a war zone. Because of social media, she says, the bounds between war and everyday life are blurring, marking "a revolutionary change in how we once imagined combat deployment."

"I thought [soldiers] being connected would be a good thing," Silvestri says. "But it's not. It produces the same headaches that I think a lot of us have here. Only it's more exacerbated. ... Not only are they in physical danger, but ideologically they are removed from our concerns and what we're interested in."

Silvestri remembers her father saying that when he left to serve in the Vietnam War, the Beatles were singing "I Want to Hold Your Hand." When he came home, they were singing "Hey Jude." He had no idea what was going on at home in between.

Since 2006, internet access has become more widely available to U.S. troops. Some outposts have "internet cafes," or "lounges," portable units where troops can share a set of computers with satellite feeds to communicate back home, Silvestri says.

"Today they know exactly what's going on back home, and they participate in it," she says.

Silvestri interviewed U.S. troops on deployment in Okinawa, Japan, and Camp Pendleton north of San Diego. Many of those she interviewed she then followed on social media as they served in Iraq or Afghanistan. She points out how soldiers often participated things like the Ice Bucket Challenge, where they dumped a bucket of ice water on someone's head to promote awareness of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Or how troops in Afghanistan created a "Call Me Maybe" lip sync of the popular Carly Rae Jepsen video.

For soldiers, change constitutes more than just being connected to what's happening at home. Social media, especially YouTube and Facebook, gives them a chance to document their own lives while at war. That could involve a soldier taking a selfie in a mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicle, one example Silvestri highlights in her book, but it also lets them post combat videos directly to the internet. One sergeant she interviewed explained the desire to capture video as a way to explain his experience to others, because it's easier to show somebody what he's been through than explain it. These videos, Silvestri writes, work as a vehicle for cohesion among troops.

Yet those combat videos, Silvestri says, are mostly meant for other troops, not for friends and family. And even though the troops are more connected than ever, often the people they left at home still have trouble understanding why soldiers sometimes can't respond to them immediately on social media, or answer the phone. One soldier she interviewed talks about how his truck went over an improvised explosive device and got blasted, and he was sent to the hospital.

"And he said, 'When I was finally able to call my wife, she was more upset' that he hadn't contacted her in a week than she was that he was injured," Silvestri says. "Because we can't imagine what it's like over there."

After conducting this research, Silvestri was left wanting more answers.

She wants to test the relationship between social media and post-traumatic growth. One thing she learned while researching for her book, she says, is that the soldiers' posts on Facebook were usually positive. She doesn't know if that's because social media makes people frame everything through "rose-colored lenses," or if it helps generate a positive outlook, but that positivity could help them handle post-traumatic stress.

The narrative for war is changing, Silvestri writes. The way it is being represented is changing, in large part because troops, while at war, still are connected to life back home. Silvestri has studied how that affects troops in combat. Now she wants to find out how it will impact them afterward.

"What's the homecoming process gonna be like for a generation that never fully left?" ♦