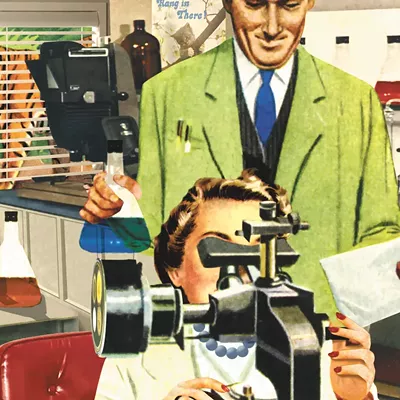

The gap between men and women in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math is well documented, and there’s no shortage of academic theories on how to fix it.

But Gonzaga professor Carolyn Cunningham argues that the solution could be found on an Xbox or Wii.

If girls were more interested in videogames, the theory goes, they would be more likely to go into fields like computer programming or game design. So the industry has poured money and time into trying to sell games to girls. Nonprofit groups hold workshops to teach girls more about videogames.

But it’s only sort of working. Even though girls are increasingly playing videogames — on consoles, PCs and phones — they still only make up about 10 percent of the jobs in the videogame industry.

Cunningham thinks she may be figuring out why. She says workshops and games designed to grab girls’ attention seem to be reinforcing old stereotypes.

In 2008 and 2009, Cunningham sat in on Girl Scout videogame design workshops in Austin, Texas, where a male instructor taught girls to design a female main character for a fashion design game using Adobe Flash. (She wrote about the workshop for a paper published last year in New Media and Society.)

The workshops taught girls how to design clothing and accessories for a central character, an avatar that was supposed to represent them. One of the girls participating had a punk-rock style, Cunningham says, and wanted to add chains and baggy jeans to her character.

“What was cool was the program allowed her to do that,” she says. “But the people that ran the program didn’t imagine that a girl would like to be looking like that.”

Cunningham says assumptions like that are getting in the way of potential success for programs that are supposed to drive girls to technology. As a society, we’re creating ways to get girls interested in technology, but then we’re trapping them in old stereotypes along the way.

“They didn’t consider that there are different ways to be a girl,” Cunningham says. “The technology can allow [girls to resist the stereotypes] but if they can’t imagine themselves using the technology in that way, then they’re not going to try it.”

The Girl Scouts’ Science, Technology, Engineering and Math program (STEM) has been lauded as a huge step for getting girls interested in male-dominated fields. But if teachers and industry leaders don’t encourage girls to think unconventionally — even just about the look of their avatar — they’ll keep girls distanced from technology and isolated on the sidelines, Cunningham says.

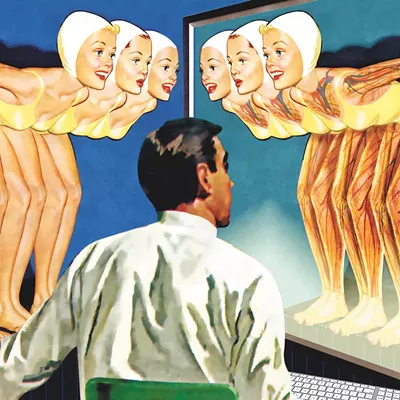

Cunningham has begun to look for this problem in other places, too. She’s been observing girls ages 8-16 playing popular girls’ games (Nancy Drew: Model Mysteries, Wii Cheer and Cooking Mama) for a half-hour, recording their reactions, and talking to them about their impressions.

The gender stereotypes in these games may seem obvious — cheerleading and cooking don’t exactly push the boundaries of the traditional female role — but Cunningham says she’s finding a bigger problem.

The games promote passive, not active, gameplay, she says. They don’t allow players as much creative interaction with the game, which is what many believe encourages players to become creators.

Even in the mystery solving Nancy Drew, players spend most of the time reading instructions on the screen. They can interrogate suspects, but only with predetermined questions. There’s some dialogue in the game, but that’s pre-scripted, too.

That’s almost never the case with games directed at boys, she says. (Case in point: Grand Theft Auto, one of the world’s most popular game series, which puts players behind the wheel as they explore cities and gun down enemies.)

“Even though content might seem stereotypical, if it presents girls with a challenge to figure out and get really involved in and they’re customizing things and trying to find different avenues to figure out the central problem, it’s going to be more interesting to them,” she says.

It becomes a circular challenge: Girls aren’t designing games, so the games aren’t engaging them fully, so they’re not becoming interested in games, so they’re not becoming game designers.

“[Equality] is something we want, and as a society we know we need to pay attention to girls,” Cunningham says. “But to really achieve the next level, we need to think about how girls’ voices are actually valued.”