For some people, the question, asked at the KSPS 6th Legislative District debate recording on Friday, may have been a purely intellectual one, a simple matter of policy: Do you believe the Washington state Supreme Court was correct in overturning the death penalty?

But for 6th District candidate Jenny Graham, the question was the deepest sort of personal.

"I definitely support the death penalty," Graham says. "I will tell you 49 reasons why. These are 49 reasons — these people no longer have a voice: Wendy Lee Coffield, Gisele Ann Lovvorn, Marcia Fay Chapman, Cynthia Jean Hinds..."

And each time she said the name of a murder victim, Graham says, she could see that victim's face.

“I know every one of those victims,” Graham says to the Inlander later. "I know their names. I know what happened to them."

The experience was almost physically painful.

"It was just like if somebody would have walked up to me and kicked me in the gut," Graham says.

And then she reads the ninth name on the list, the ninth victim of the Green River Killer: "Debra Lorraine Estes."

Graham's sister.

"Every time I read one of those names — you do not understand that I was picturing my sister with the garrote around the neck, and him tightening it tighter and tighter and tighter, and then kicking her into a hole," Graham says. "She was 15. She was barely 15."

In 2014, on Mother's Day, Jenny Graham walked into the Walla Walla State Penitentiary to have a meeting she'd spent two years jumping through hoops to make possible: A meeting with her sister's killer.

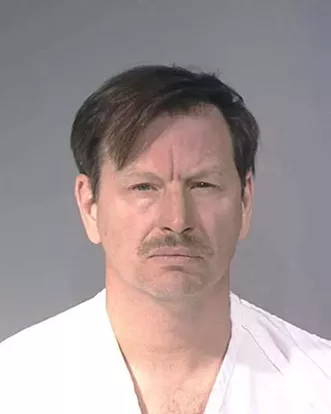

He was clean cut. He looked well kept. Graham was sitting extraordinarily close to him, a mere pane of glass between her and Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer.

"I had to be willing to go to the most painful places that a person can ever go in their life," Graham says. "I’ve never been one to back down."

But Graham says she needed to figure out why Ridgway had done so many of the things. She brought a printed-out list of dozens of questions with her.

"When I went to talk with him I didn’t have an ounce of hate in my body," Graham says. "I had questions he was the only one who had answers to."

Graham was 17 when her sister was murdered by Ridgway. At first, her sister simply went missing. She grew up in an abusive home. Her brother and her sister would run away frequently to escape that abuse.

The last time she saw her sister, Graham says, they had gotten into a fight over Estes taking some of Graham's stuff.

There's a hell, Graham says, that comes with not knowing what happened.

You leap at the sound of the phone call with a twinge of hope that your missing loved one might be on the line. You see someone who looks like them in your peripheral vision and you turn your head in their direction.

"Every time you hear somebody who sounds like them, you drop what you’re doing," Graham says. "My sister was missing for six years before she was found."

Graham says she realized that the woods she used to walk through to get to Thomas Jefferson High School in Auburn, Washington, were the same woods near where Ridgway had been dumping his bodies. She says she knew two other names on Ridgway's list of victims personally: Becky Marrero and Kelly Lee McGinnis.

"That could have been me," Graham says.

As Graham listened to the tapes of Ridgway being interrogated, she heard him describe the utter lack of emotion he claimed to have felt as he strangled his victims, she says it hit her like a ton of bricks.

"It resonated with me... I understood exactly what he was saying," Graham says. "I got it. I understood that."

Graham had sometimes experienced a feeling of deadness, of being shut off from emotion. Ridgway, like her, she says, had been a victim of horrible child abuse. She worked for years to deal with that feeling. Shutting down was a survival strategy. But she'd gone in a different direction as Ridgway.

"I was in the position where I was protecting the siblings," Graham says. "I was protecting my mom. That was my life. That's who I am."

But Graham says she'd been worried about one of her own close family members going in a dark direction because of the abuse they'd all experienced.

And so for Graham, seeking out her sister's killer was a way to understand what had happened in Ridgway's mind and his life that set him on his path. Most importantly, she wanted to know what could be done to save a person from that kind of darkness.

"I needed those answers," Graham says. "This was about healing for me."

She says she said a prayer for Ridgway's victims — and for Ridgway — before walking into the prison unit for her conversation with the serial killer.

"All 49 victims were there with me," Graham says. "A lot of the questions I asked, may have been questions they would have asked."

She didn't know if she'd only have a few minutes in her conversation with Ridgway.

"Nobody told me how long I was going to have, and what the rules were. I had to be prepared for anything," Graham says. "I was really afraid if I said something wrong that they would shut it down. I had to figure out a way to connect to him, in which he would talk to me."

The conversation ended up lasting four hours. They talked about what led Ridgway to become a killer.

"We talked about his life. We talked about 'how did you get there?'" Graham says. "The question I’m asking as a mom and as someone who has worked very hard to protect their neighborhood was "what can we do to get [potential serial killers] some help?"

She says that Ridgway talked about the disconnect he felt growing up. Graham said that Ridgway wished he would have been able to have more of a relationship with his grandfather growing up, one of the people he admired. She says Ridgway said that maybe if he had someone to talk to growing up — someone who would have intervened with him as a kid, he could have gotten help.

"You want to know what else strikes me?" Graham says. "If you listened to any of the [Ridgway interrogation] tapes, he stutters in those. During our conversation — a four-hour conversation, he did not stutter one time."

Graham says she isn't sure why.

There's a lot that Graham doesn't want to talk about in her conversation with Ridgway.

The conversation was private. It was personal. There are things he's shared about his other killings that haven't been made public.

But she says that, ultimately, she left their meeting feeling "at peace."

"I was literally told, 'Nothing good can come out of this meeting,'" Graham says. "They were wrong."

That doesn't mean the pain is gone, of course.

Graham says she has the pictures of her sister's remains from when her body was found, with the garrote wire still tied around her neck. She still hasn't ever been able to look at them.

Ridgway's life wasn't spared because of the Supreme Court decision. He wasn't on death row at all. He struck a plea bargain. But that's exactly Graham's point: The threat of the death penalty was what convinced Ridgway to strike a plea in agreement to help police locate remains of some of his victims. It's what helped convinced Ridgway to confess to murdering 49 people (though he's credited with killing far more).

"They don’t understand that were it not for fear of the death penalty, Gary Ridgway would have zero incentive to give up any information," Graham says. "He didn’t want to give those remains up. Those were his trophies."

Graham's opponent, Dave Wilson struck a nuanced position: He was opposed to the death penalty in general and was concerned about the issues with racial disparity, but did support it in rare circumstances.

That answer earned Wilson some blowback from some of those on the left, with Spokane City Councilwoman Kate Burke criticizing Wilson's "partial endorsement the ineffective, expensive and unfair death penalty."

"So this is a tough question: I’m somewhat conflicted on it. On one hand I’m concerned, because too many innocent people have been convicted and put to death. However, there are some crimes that are so horrible I believe they do warrant the death penalty: crimes like terrorism, murder of a first responder, serial killers or really horrible murders.

"The death penalty is also an important tool for prosecutors, because it allows them to bargain with murderers to get cooperation. I think that’s a legitimate argument to keep the death penalty.

“However, I think we also should be careful and have a careful discussion about this in the Legislature. Because the reasons that this was overturned I believe are valid: disproportionate [impact] on people of color.

"I would like to see it kept for those circumstances that I mentioned, but this should be a rare thing. And it should be only in those circumstances."

In her rebuttal, Graham stressed that she was an expert on the Green River Killer case.

"The facts of the matter are that I am an expert on this case. There are more white people on death row in Washington state than colored people. That's a fact.Graham later apologized for mistakenly using the phrase "colored people" instead of "people of color" and says she's reached out to connect with NAACP President Kurtis Robinson to emphasize that she didn't mean anything malicious. She says it was difficult to choose her words correctly

"The bottom line is this: We victims asked for this to go to a vote of the people. The court doing it this way, sidestepped the people's voice. We need, as victim's family members, to be heard, there are plenty of people I know who want to vote on this issue."

"I was trying to say those names, trying to breathe, trying to get through it, trying to get people to understand that these were human beings," Graham says. "I didn’t mean to hurt anybody."

But it's also fair to say that her assertion that more white people are on death row than black people doesn't understand the Washington state Supreme Court's concern: The rate of sentencing is racially skewed, the court pointed out, concluding that "black defendants were four and a half times more likely to be sentenced to death than similarly situated white defendants.”

It's also important to recognize that even people who've had loved ones murdered by the same person can have radically different views of the death penalty.

Nova Reeves, the daughter of one of Ridgway's other 48 victims, argued in a February op-ed that the death penalty was not the answer.

"Instead of wasting hundreds of millions of dollars on carrying out the death penalty, we should improve victims’ services and direct resources toward unsolved murder investigations and prisoner rehabilitation," Reeves writes. "Victims deserve better than the hollow promise of another death."

Tune into the debate tonight at 7:30 p.m. on KSPS.