Generally, as a species, we have a hard time learning new information that contradicts what we previously thought we knew. We tend to mistake believing something for longer with it being truer.

Like most of us, I've experienced this firsthand. Specifically, I recall being told that Pluto wasn't a planet anymore.

I was outraged. How could Pluto be a planet one day and not one the next? It had been a planet my entire childhood, my entire life, forever! And now for reasons I didn't completely understand, it wasn't.

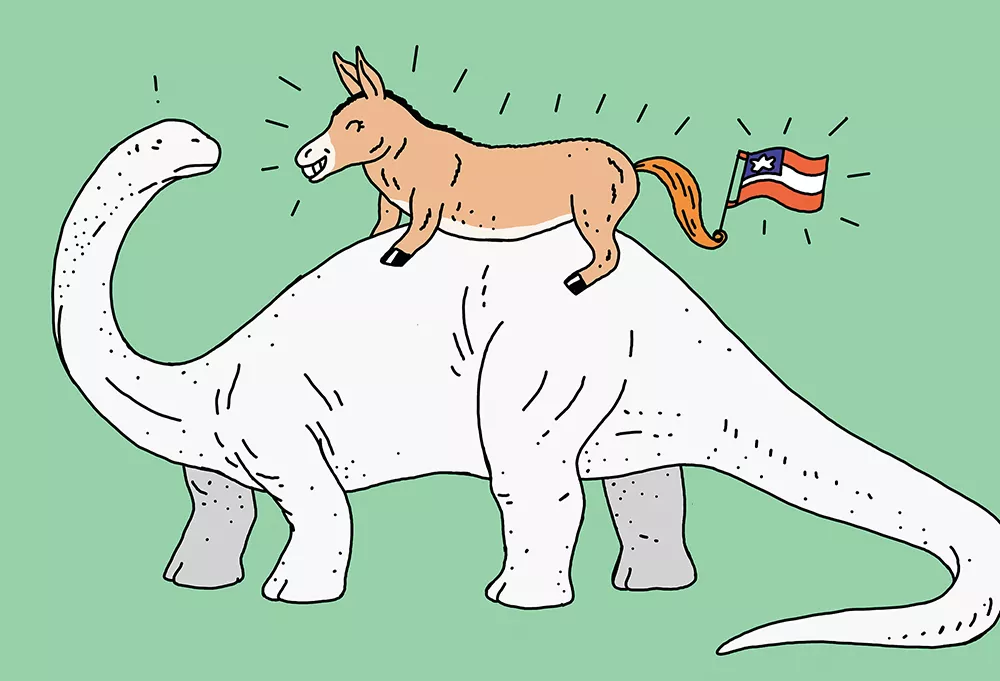

An even more crushing lesson, contradicting my childhood knowledge, was the assertion that the brontosaurus, that long-necked wonder of a dinosaur, had never actually existed. Apparently, it was just a misnamed skeleton of another, already-discovered dinosaur too hastily named by an overeager paleontologist.

Except, in this case, three years ago a new set of paleontologists reasserted the legitimate existence of the "thunder lizard" (as the name brontosaurus translates to). It's now a matter of some dispute. Personally, I choose to believe the brontosaurus is real. Not based on any facts or review of the scientific literature, but just out of my deep and long love of the creature.

It's not just us regular, non-scientist folks who have a hard time absorbing new information. It's been suggested that major breakthroughs that contradict old, accepted knowledge can take a generation to be accepted within the scientific community — potentially because you have to wait for a generation of scientists to pass away first.

Not all supposed knowledge takes an entire childhood or generations of scientists to set in.

Just consider election night earlier this month, where it only took a matter of hours for many to start clinging to a truth that had barely been reported. Results from that night suggested that Democrats had a decent, but not necessarily stellar election. They'd secured a modest majority in the House, but lost significant ground in the Senate. Many suggested it was a split decision.

But over the past couple of weeks, as more of the votes have been counted, the reality has become clearer: It was a tremendous night for Democrats. Their pickups in the U.S. House are nearing 40 seats and their popular vote margin could be the greatest for a party out of power since we started tracking such information.

And though we may be able to reckon with us not fully understanding a far-off rock flying through space or correctly interpret a partial giant, fossilized skeleton, it can be even more difficult to accept that the votes counted and reported initially may not represent the whole story.

Some, a certain president included, suggested that continuing to count votes that could ultimately change the outcome was tantamount to fraud — as though what we knew on election night was somehow more true than what would be learned about the voters' will by counting every ballot.

Alternatively, some, across the political spectrum, decried the speed of the count. "Why can't we get all the information on election night?" cried many a pundit.

Personally, I think accuracy, not speed, is the most important consideration in counting votes.

Knowing what's true can take time, even in something as straightforward as counting votes, and with something so important and basic to our democracy, we must be willing to take the time to count and, if necessary, recount to determine what really happened.

In fact, in researching this column, I was reminded that the debate around Pluto's planetary status was reignited again earlier this year. A group of scientists argued that not only was Pluto a planet, but that several moons were, too. It's just another reminder of the uncertainty of our initial knowledge.

And also, apparently, that a planetary recount may be in order. ♦

John T. Reuter, a former Sandpoint City Councilman, studied at the College of Idaho and currently resides in Seattle. He has been active in protecting the environment, expanding LGBT rights and Idaho's Republican Party politics.