Downtown Spokane was beset by disorder, addiction, crime and public intoxication, many of the loudest local voices argued. There were police records to back it up — 80 percent of arrests in Spokane, these sober-minded voices argued in the local newspaper, were due to one substance in particular: alcohol.

You could say the choice that Washington state voters made was about compassion. Saving lives and saving souls didn't mean allowing troublemakers to feed their addiction, to drive themselves to ruin and death — it meant saving them from themselves. Think of the children.

In November of 1914, five years before nationwide Prohibition, Spokane voters were asked to ban the sale and manufacture of alcohol. By then, they'd already been exposed to at least two decades of arguments about the dangers of beer and liquor.

Ax-wielding feminist temperance movement leader Carrie Nation had hyped her 1910 visit to Spokane in the newspaper by teasing the possibility of smashing local saloons, while traveling preacher Billy Sunday decried establishments that sent men home to their wives as "maudlin, brutish, devilish, vomiting, stinking, blear-eyed bloated-faced drunkards."

The Spokesman-Review — which bragged in its pages about how the "permanent, earning classes" made up its readership — championed the temperance cause.

West Valley High School history teacher Ned Fadeley, who dug into Prohibition in Spokane for his 2015 master's thesis, says opposing liquor was a way of signaling that you were sophisticated and respectable. You're different from all those immigrants and Catholics and unruly laborers.

"By voting dry you're conspicuously asserting you're not part of that lower class," he says.

But plenty of locals just as passionately argued against Prohibition. A Lutheran reverend argued that "it is a psychological fact that prohibited joys tempt the strongest," and pointed to all the wine consumed — in moderation, of course — in the Bible.

"Those addicted to the curse of alcohol get it anyhow," one Spokesman-Review letter-to-the-editor read, and damage done by alcohol paled in comparison to the damage done by "corsets and high heels."

Most city-dwellers — those supposedly victimized by alcohol-related crime — opposed Prohibition. But rural voters — and the state as a whole — overwhelmed the skeptics, passing the 1914 vote in favor of, as supporters put it, "sobriety and decency."

And you know what? At first, it actually appeared to work. Arrests plummeted. Bankruptcies fell. But the predictions of the skeptics also held true. People still managed to find alcohol.

Speakeasies soon popped up in downtown Spokane, including in buildings that today hold the Ridpath, Atticus and Garageland. Alcohol still flowed through Trent Alley, and Trent Alley continued to be portrayed in the press as a den of depravity. Underground tunnels originally built for pedestrians to avoid streetcar traffic became routes for smuggling liquor. The police repeatedly conducted raids and posed proudly for photos of smashed stills.

But not everybody got raided.

For his thesis, Fadeley plotted out all the Prohibition-related arrests on a map. It was what wasn't there that stood out.

"I plugged in the addresses, and I noticed that none of the addresses corresponded with any of the affluent neighborhoods in Spokane," Fadeley says.

It wasn't, of course, that rich people didn't drink. Even once the 18th Amendment banned the manufacture, sale, and transportation of liquor nationally in 1920, it wasn't hard to find alcohol.

The authorities wouldn't dare bother a wealthy man like mining magnate Amasa Campbell, says local American drinking history expert Renee Cebula.

"Mr. Campbell carried a flask in his pocket and it was full of whiskey his entire life," Cebula says. A speakeasy in a home in the swanky Cliff-Cannon neighborhood wouldn't get raided. If you were poor, you might have had to settle for homebrewed moonshine. But with money and the right connections, it was easy to get your hands on some quality whiskey.

Blame Canada.

With the Canadian border less than 100 miles away from Spokane, a whole new industry of amateurs-turned-rum-running smugglers got rich selling Canadian whiskey at a 400 percent markup.

Former liquor smuggler Edmund Fahey wrote a whole memoir, Rum Road to Spokane: A Story of Prohibition, brimming with feats of rum-runner shenanigans, including bribes to corrupt law enforcement officers and bullets fired at the radiators of pursuing Border Patrol vehicles.

Sure, you could get caught. But the penalty for rum-running was a lot higher than the penalty for moonshining. Fadeley compares it to the way that, for decades, crimes involving crack were punished so much more harshly than crimes involving cocaine. A poor man's drink gets you just as drunk as a rich man's drink — but society was a lot more scared of the poor man.

In fact, Fahey writes in his memoir, the smuggling business thrived precisely because of the demand from "honest, respectable citizens." He writes about how professional men introduced women to the illicit pleasures of drinking.

"That first drink was taken for the thrill of defying a law they considered as intruding on their personal rights," Fahey writes in his memoir. "But the defiance soon developed into a fondness for alcohol."

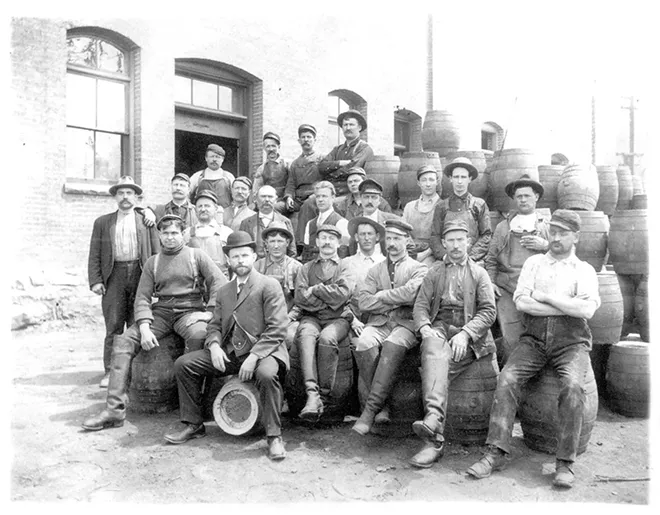

Even the most successful people, of course, were victims of Prohibition. German immigrant Bernhardt Schade had been the owner of Spokane's Schade Brewery, which once pumped out around 80,000 barrels of beer per year. Prohibition forced him to innovate, turning his brewery into a manufacturer of soda and "near beer," a non-alcoholic beer.

By the 1920 census, Schade was officially out of a job. By 1921, struggling with illness, Schade committed suicide. A decade later, as the Great Depression hit, the vacant Schade Brewery building had become a campsite for transients. It took Prohibition ending for the building to be resurrected as Golden Age Brewing, which quickly became one of the biggest breweries in the region. Schade's tragedy, however, is one that got recorded.

The fate of "the poor woman who was arrested, fined, and jailed for selling beer out of old tomato cans to thirsty duffers at Spokane's Downriver Golf Course in the late '20s," as Fadeley writes about, is a lot more obscure.

Fadeley suggests the surge of Roaring '20s nostalgia, with high-priced cocktails and faux speakeasies, is almost offensive, white-washing a policy that "succeeded primarily in turning ordinary citizens into overnight criminals, and in so doing sent countless scores of Americans to jail, the poorhouse or an early grave." ♦