This exhibit was co-curated by Maya Jewell Zeller (age 40) and her daughter, Z. (age 10), who is responsible for about half the language, and most of the fun.

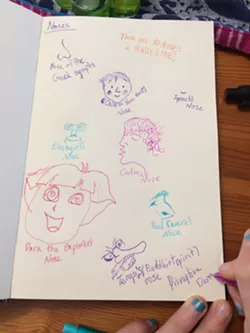

The nose of the Greek nymph faces to the right, and curves down, then up, with a half-circle at its base, like a small moon.

In We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, the child’s nose points left, creates a squiggly-straight. He’s heading into the swishy swashy, so this makes sense. Can he smell the bear?

(“Wishy washy is a Pokémon,” says the little brother, age 7.)

Sprout’s nose is just like ... hmmm. A dip, like a bowl that wouldn’t stand up.

Tengu, a type of Buddhist spirit’s schnoz, looks like a foot that’s very flat and doesn’t have any toes. Tengu is a “disruptive demon.” We find him delightful.

The nose of Elastigirl is an upside-down tunnel with a flat bottom. Elastigirl, in this context, is a small figurine, aka Mrs. Incredible, used as a placeholder for the mom. The children and dad bought her for the mom when she was out of town. Every week, the mom leaves town for work, and Elastigirl sits where her plate would sit, and when she comes home — having woken at four, usually, to complete her workday early and arrive back in town by dinnertime — she joins the family at the table, where they commence catching her up on all things, nose and not. She’s tickled when Elastigirl first appears. They often refer to the mom as a superhero, anyway, and thought she deserved an action figure in her honor — flexible and strong, ready to battle whatever threatens her family. Elastigirl can’t get sick. But that’s because she’s made of plastic.

Cadmus’s nose looks like it is connected to his hair, and is missing nostrils.

Sophie Foster’s nose is flaring out and looks angry. (But intelligent.)

Sophie Foster is from Keeper of the Lost Cities, and this description of her nose is based on the cover of the 8th book, for which the daughter waited forever. Sophie Foster is an elf, raised by humans, until she turned twelve, and then she was adopted in the elf world, aka the Lost Cities. She was developed in a lab, because even though she’s a person, they tweaked her genes to give her superpowers, like being able to teleport. The daughter’s friends sometimes call her Lady Fos-Boss, which is one of Sophie’s many aliases. So the daughter is sort of a superhero too. But, the mother notes, she was not made in a lab. She was not raised in the lost cities. She was raised here, in the Nose Museum, before it was the Nose Museum, where always there are books and thinking.

Dora the Explorer’s nose looks like Sprout’s nose, on its side.

Paul Revere’s nose looks like the end of a fat banana, with a dragon eye at the bottom.

In Dorothea Tanning’s Birthday, the woman’s nose has two parts: one nostril behind the base of the nose, and one part on top, like a normal nose.

There are no noses in Madeline.

* * *

In the daughter’s journal, she has meticulously sketched each of these, after we embarked on our nose study, piling books on the table — children’s collections, middle grade novels, and art books. We’re making a nose museum, we decide. The first room was Depictions in Art. Next, we’ll look at Famous Noses in Literature, following ours wherever they lead, and lingering as we like.

The mom is home from work indeterminately for now, and this is day four. She is teaching remotely, and needs to get her grading done, but the Nose Museum is part of the inquiry learning of her new homeschool/unschool curriculum, and so she’ll spend what would normally be commute time following her daughter and son from room to room, reminding them to wash their hands, don’t touch their noses.

* * *

Among the famous noses in literature are Pinnochio’s, Cyrano de Bergerac, and “O Best Beloved” in Kipling’s “The Elephant’s Child.” But the children are most interested in the Brit popular for “literary nonsense.”

So we spend thirty minutes reading about Edward Lear, who wrote, among other famous British poems, “The Dong with the Luminous Nose” (cue giggles and damp crow’s feet), and then we watch people’s animated renditions on YouTube. This dissolves into more gut-laughter for the brother, who has joined us. Our favorite video is one for the Jumblies, little green people, like Leprechauns, but with blue hands, and they “went to sea in a sieve.” It’s St. Patrick’s Day, and we’re thrilled to see these adventurers, when none of us are allowed now to venture too far from home. The yard, the trails, the extensive shapes of our minds — these are where we’ll be learning during the pandemic. We are the museums, and the classrooms.

In the daughter’s journal, she notes: “Edward Lear wrote poems, songs, and short stories, and died in 1888.” We don’t talk about how he died. (Though it wasn’t of a respiratory infection — it was heart disease.)

* * *

Like other respiratory viruses, SARS-CoV2, a coronavirus, enters the body through the mouth, eyes, or nose. It doesn’t matter what shape your nose is, or how it appears in artistic depiction. It doesn’t matter if you’re a supermom or a really generous and creative child or a goofy or serious artist. If someone carrying SARS-CoV2 coughs or sneezes, and the small viral droplets reach your nostrils, and you breathe them in, the virus can attach to cells in your airway and begin to attack.

* * *

Salmon find their home rivers through scent. Also, fish can smell when they are in dangerous water — even in very low doses, they detect chemicals. They can swim away to keep themselves safe.

Dogs’ sense of smell is ten times greater than humans. We know this already — we have a hound.

Male moths have smell sensors on the end of their antennae.

Rats live by their sense of smell.

A human’s upper nasal cavity is located near/ under your eye; sense of smell and eyes are therefore related.

The technical term for sense of smell is olfaction.

Your overall nasal shape is formed by age 10. You cannot smell when you have a cold, because the smell molecules cannot reach your olfactory receptors.

Normally, though, humans can distinguish 20,000 different smells. Humans’ sense of smell is 10,000 times stronger than their sense of taste.

1 in 1000 human beings don’t think skunks are stinky.

This makes us laugh again. We laugh, and we ask a lot of questions.

What about if you can’t smell at all? The technical term for that is Anosmia, from which about two million people in the U.S. suffer. Do these people not smell danger?

* * *

“Let’s go back to the art room,” one of us says on day seven. “I like it there.”

“Me too,” the other says.

We find a stack of art books and begin to leaf through.

We’re not sketching any more, just paying close attention.

“Well, that’s an interesting nose,” one of us says. We’re looking at Goya’s The Advantage of Taking Life Easily, in which the man sits on a bag of some sort, tied at the end like he’s done a lot of yard work and put all the debris inside. His nose is long and flat, directing our eye toward the woman standing opposite him, holding one end of a string that then loops around and around both of his wrists, like an overly intricate game of cat’s cradle. A hunched, hooded woman sits between them, forming a triangle, and the spool end of this string. We don’t know what they’re doing, besides holding string and “taking life easily,” which is what we’re supposed to be doing now.

All of Goya’s seem to be long. They are not distinctive features in Goya, so why we have chosen to include him in the Nose Museum, we’re not sure. But we like it here in this room, so we’ll stay and look awhile. It’s good to get away from the large, focused nose.

The young one of us points out that Goya’s self-portrait shows him “kind of sinister and sad.” But many artists portray themselves darkly, she says.

That’s because their lives were hard, says the supermom. The times were hard, but they made art.

We’re waiting to see how to portray this time. For now, we’ll wander the rooms, take notes. We have a lot more to learn in the Nose Museum. ♦

Maya Jewell Zeller is a mother, writer, editor, and professor. Author of three collections of poetry (one an interdisciplinary collaboration with painter Carrie DeBacker), Maya teaches for Central Washington University and edits for Scablands Books. Follow her on Twitter @MayaJZeller, or visit this website, where she is currently posting prompts for inquiry learning.

Z. Zeller, age 10, is an avid reader, dragon enthusiast, dog owner, and big sister. On her private blog she goes by The President of Everything. Normally a student at Brentwood Elementary, during the school closure she has been reading a lot of novels. But then, she’s always reading a lot of novels. She does not have any social media accounts.