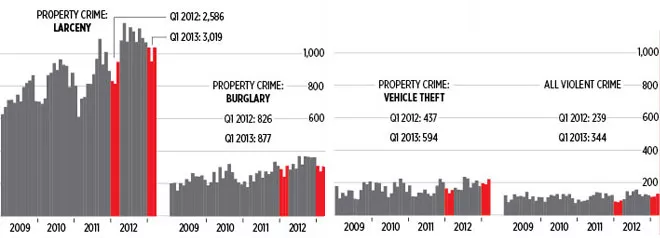

About 2,095 vehicles got stolen off Spokane streets in 2012. Records show 3,114 residential burglaries and 713 commercial or non-residential burglaries. At least 675 bicycles went missing.

Nearly everyone in the Lilac City can share some horror story — either their own or another’s — about returning home to discover a door kicked in, experiencing the shock of an empty parking space or cursing a broken bike lock.

Spokane crime rates in 2012 show nine out of every 100 city residents could expect to be victims in a property crime. While thefts and break-ins rarely make headlines, each crime shakes its victims, leaving them feeling violated and frustrated.

“If you’ve been victimized, your whole world’s been turned upside down,” says Christy Hamilton, director of the Spokane Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) program.

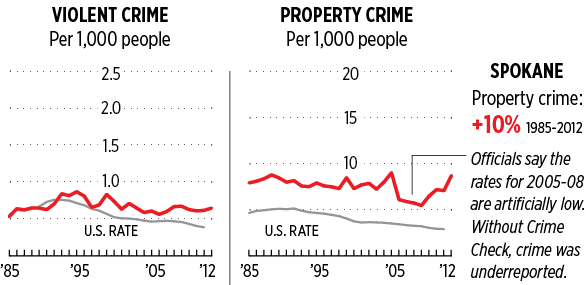

In crime data going back to 1985, Spokane shows a long history of struggling with property crime rates that run against national trends. The numbers vary depending on the time frame: Up 10 percent since 1985. Up just 4 percent since 1987. Up 13 percent since 2000.

But the pattern is clear — property crime has gone up or held steady in Spokane while falling dramatically in most major American cities. In 2012, Spokane’s property crime rate ran higher than corresponding rates in Seattle, Portland, Detroit and New York City.

City officials and residents have voiced outrage over the increasing rates. After infamously announcing the elimination of its Property Crimes Unit in 2011, the Spokane Police Department has since reversed course, introducing new patrol initiatives, policies and investigation units to crack down on property crimes.

So far this year, crime rates remain high, but they have come down from peak rates seen last fall.

“Spokane has a crime problem,” Police Chief Frank Straub says. “I don’t think it’s perception. It’s reality. … [But] I think we’re moving in the right direction.”

Beginning this year, the Spokane Police Department has intensified efforts to identify repeat offenders and increase officer presence in high-crime neighborhoods. Straub, who took over in September, has reorganized the department around a new data-based policing strategy and ordered the targeting of “hotspots” citywide.

Mayor David Condon and police officials have since heralded small-scale successes in targeted areas, pointing to decreases in property crimes in downtown and the some of the northeast neighborhoods, which sit north of the river and east of Division Street.

“It’s looking at where those crimes rates are and putting police officers where those crime rates are,” Condon says. “Is it where we want it to be? Absolutely not. … I’m not pleased with where we are yet by any means. But are we tracking the right things? I believe we are.”

Local crime rates have dropped this year compared to significant spikes in both property crimes and violent crimes last fall, but the rates remain higher than the first quarter of 2012. It’s too early to tell whether crime will go back up as it typically does in summer months.

New citywide crime statistics, released Tuesday, show small increases in overall crime when comparing the beginning of this year against 2012. Total crime incidents went up just 3.7 percent across the city. Property crime remains up 4 percent over last year.

Violent crimes have held steadier. Spokane again bucked national trends by staying essentially level while other cities recorded dramatic declines since the early 1990s. The 2013 rates have dropped by less than 1 percent compared to last year. Straub pointed to specific reductions in the number of homicides, rapes and robberies against individuals.

In recent months, Spokane Police officials have struggled to debunk the widespread community belief that the department no longer cares about property crimes following a stark announcement in late 2011 that the SPD Property Crime Unit had been eliminated and just 5 percent of cases would be investigated.

While the previous police administration made it clear property crimes would be a low priority, Straub has since described the 2011 announcement as a clumsy ploy for more funding that has lived on as an “urban legend.”

“The Spokane Police Department investigates all crime, property crime and everything else,” Straub says. “We’ve never stopped doing that.”

Property crimes now get investigated as part of the Fraud Unit. Straub pointed to a more than 17 percent decrease in property crimes in the downtown area. The West Central region has also seen a more than 10 percent drop in property crime compared to last year.

“What the community is seeing is focused, data-driven policing,” Straub says. “We are bringing crime down.”

Why does Spokane continue to see property crime rates higher than similar sized cities like Boise or Tacoma? When asked in April about the social factors contributing to local rates, Straub singled out the impacts of poverty and drug issues. He also suggested a need for increased social services and mental health programs.

“We have a large part of our population that is below the poverty line,” Straub says. “So clearly poverty is a driver. … We [also] have so many people who have double issues. They have mental health issues and they have drug and alcohol dependency issues. So when we talk about crime phenomena, [those] are driven by those types of societal issues.”

Spokane and Kootenai county law enforcement agencies came together in April to announce a joint property crimes task force. Led by the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office, the task force will share information about thefts and suspects to track crimes across multiple jurisdictions.

Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich says the unincorporated county has seen a dramatic decrease in burglaries, down 53 percent compared to last year, after forming a similar task force to target burglaries in 2012. The agencies planned to meet this week to discuss what information and resources each can bring to the table.

“It’s moving right along,” he says.

Knezovich says several factors contribute to confusion over regional crime rates. He cites the “Crime Check dip” for creating an artificial decline in crime rates from 2005 to 2009 when the Crime Check program shut down for budget reasons, eliminating a popular program for tracking citizen reports.

When the program came back in 2009, crime rates started to rise up again dramatically. Knezovich argues the rates haven’t really increased, but have returned to more regular levels previously recorded before Crime Check went away.

Authorities all agree collecting the best information on property crimes will help investigators crack down on local thieves. Hamilton, with the COPS program, says even if an officer does not respond to a call, the information still helps provide a better understanding of neighborhood crime.

“We really, really encourage people to report because that’s how we know what’s going on,” she says.

Officials also encouraged residents to get involved in community policing programs and serve as stewards of their neighborhoods alongside local departments.

“We can and will reduce crime,” Straub says, adding, “We’re not going to rest until we start seeing double-digit crime reductions instead of double-digit increases.”

Running the Numbers

A burglary here, a robbery there — the numbers don’t add up to much unless you can see the bottom line. Someone has to look at the whole picture to find a little meaning, some clue or pattern for predicting future crimes.

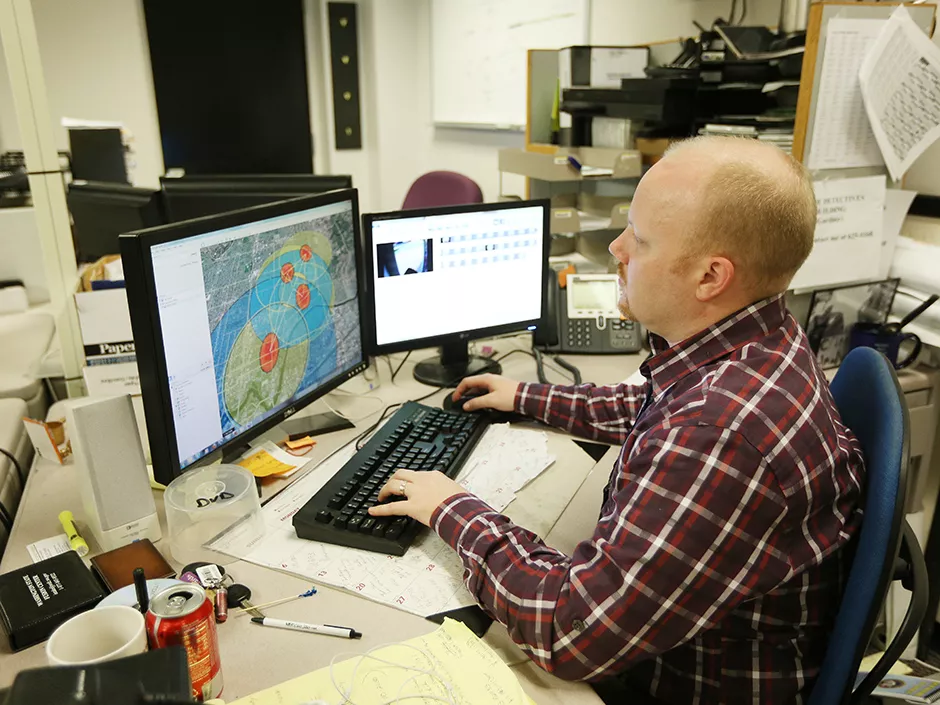

With thousands of police reports filed each month, crime analysts with the Spokane Police Department constantly review, dissect and map crimes to identify the repeat offenders and hidden trends driving local statistics.

Cmdr. Brad Arleth, who oversees the Crime Analysis Unit, says police analysts refine raw reports to pick out the helpful information that can be used to put patrol officers in the right places at the right times.

“You can really see what it is that we need to focus on,” he says, adding, “A lot of times, it’s the story behind the numbers.”

Under the department’s new CompStat data-driven policing model, the Crime Analysis Unit has taken a central role in providing quick-turnaround intelligence, historical context and emerging patterns for investigators.

“Our main mission is to try to put the most timely, accurate information we can out to the troops on the street,” senior analyst Ryan Shaw says.

The unit’s four analysts examine reams of reports to compare locations, times, stolen goods and other details. They can find similarities between multiple crimes or determine whether several criminals might be striking separately.

They can also predict what time of day crimes may be more likely to occur or what businesses might be vulnerable to thieves.

Analyst Tom Michaud says many crimes simply involve family issues or personal disputes. But analysts try to pinpoint predatory repeat criminals or problem locations that officers can target to put a larger dent in crime rates.

“There’s a lot of stuff we go through,” he says, “to try to break it down to what’s the biggest bang we’re going to get as an organization.”

— JACOB JONES

A Matter of Perception

Against the backdrop of the national gun debate earlier this year, Pew Research Center asked Americans: Has the number of gun crimes gone up or down compared to 20 years ago?

Most people — 56 percent — said it’s up. Only 10 percent said it’s down. (The rest either said it’s the same or did not know.) The kicker is that gun crimes are not only down, they’re down dramatically. The gun homicide rate is half of what it was in 1993, and other violent gun crimes are down 75 percent.

The survey was one more example of how the national decline in crime has gone unnoticed: When it comes to crime, Americans persistently believe it’s getting worse. Despite numbers that show crime rates in most places declining or holding steady, more than 60 percent of people surveyed by Gallup in recent years said there’s more crime than there was a year ago.

Even in cities with the highest crime rates, only a fraction of citizens will be victims each year. So how do people know whether it’s getting better or worse? Perceptions of crime are shaped by a combination of personal experience and the media, says Michael Gaffney, the associate director of the Division of Governmental Studies and Services at Washington State University. He says people have a tendency to think of crime as one big concept, fueled by everything from seeing a sensational homicide on the news to hearing word of mouth that a neighbor’s car was broken into.

Gaffney has been involved with studies that ask “how much of a problem” various types of crime are, from litter to murder. They’ve found how the question is asked makes a big difference: People are more likely to say serious crime is a problem at the community level than if they’re asked about whether it’s a problem “in your neighborhood.” Closer to home, smaller problems like graffiti are rated as more of a problem. Essentially, people perceive crime as a problem at large, but less so on their own blocks. “I’ve seen that to be the case every time we’ve done that study,” Gaffney says.

In Spokane, perceptions of rising crime are not completely off the mark — but hyperawareness is also on the rise. As breaking news teams compete with citizens listening to scanners for minute-by-minute social media updates, law enforcement leaders have made a point to caution people against drawing conclusions from every frenzied crime report. As Spokane News, the Facebook-based community of amateur crime-watchers, has ballooned in popularity this year, its users occasionally express ambivalence about the effects of following every siren. “Heard great things about this site from a friend,” a user posted in February. “Actually, she told me to maybe stay away, it would give me anxiety! LOL.”

— LISA WAANANEN