Rumors began last spring. Outside magazine had selected Spokane as one of seven “dream towns,” a place where citified outdoor sports zealots could live their lives of quiet desperation a little closer to a decent restaurant and a blue ribbon trout stream. "Where to Find It All,” the cover exclaimed when the issue hit newsstands in June, "A Real Job. A Real Life. And the Big Outdoors.''

Despite the unabashed praise writer Mike Steere lauded on Spokane (“... a refuge the whole weary and frightened world is looking for... "), the one-page profile is tinged with a few other stinging observations. The prices of life in our inland paradise, according to the author? "True alternativeniks may shrivel in this essentially big small town. Stridently festive parks and public buildings don't quite revive a tired central business district." Ouch. But the comment that cut to the bone? The gestalt poured in the wound? "The city seems to have a deep, very '90s problem: low self-esteem, brought on by an old rap labeling it an inter-mountain toad on the wrong side of the state."

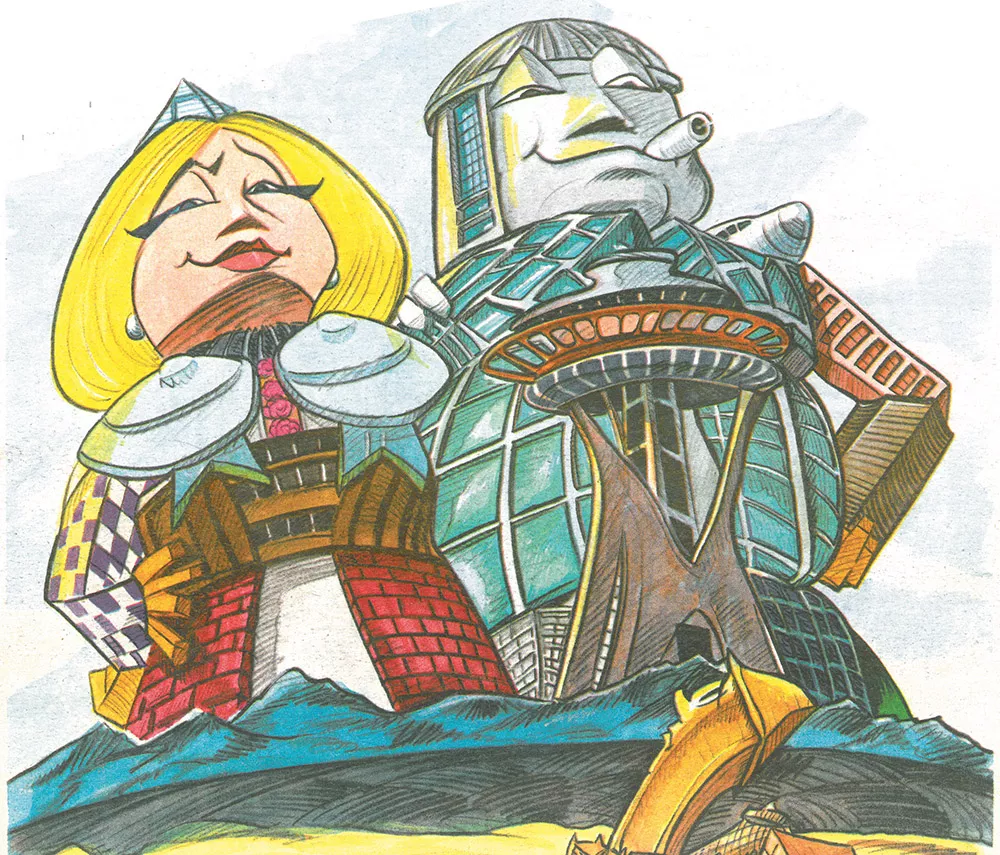

Whether acknowledged or not, the widespread attitude that Seattle is Washington's favored son and Spokane its red-headed, bastard stepchild has stuck tenaciously. In response to Outside's claim that Seattleites are quietly slipping away from the city and relocating in Spokane, a Seattle Weekly writer recently commented on the Outside piece that he was "dubious, having met too many refugees from The Can who came to Seattle and stayed.'' Never mind that this is the second largest city in the state, it's still regarded as, I once heard a young man in Missoula say, the City of the Living Dead.

When I left Seattle to move here two years ago, I was sent off with sympathy. "You'll be back," said one friend shaking his head sadly. "I give you six months." "Spokane," said another "Why not just move to Oklahoma?"

I couldn't quite muster up the courage to tell them I was actually excited for the move to a place with seasons — where it snows in the winter and grows hot in the summer; where a short (sans traffic) drive brings you to all the mountains, lakes and rivers you could ever hope for; where a person living a few cents above poverty level could still afford a decent apartment, and those making a decent living could live like kings.

Spokane held the promise of both independence and opportunity; a place where you could make things happen for yourself, not simply assume a spot in line. I arrived with the same feeling that investors must get when they know they've picked up a good stock. And I still feel it. Not, as Outside would suggest, that I can have it all — but that l can have enough.

Count me, then, among the alternativeniks who have come here and not shriveled. Well, at least not entirely. I have been known to threaten napalm strikes on North Division and East Sprague so that we might wipe out the entire garish sprawl and start over. Occasionally, I succumb to fits of frustration and come dangerously close to grabbing store clerks by their lapels and saying. ''No, I do not want you to special order that, I want you to carry it.” I mope around each summer when the Gonzaga University students go home and KAGU-FM — the only city-wide source of alternative radio available for 300 miles — goes off the air. And sometimes I stand and throw pennies into Riverfront Park's big red wagon, wishing with varying degrees of desperation that 10,000 young people would march into downtown and erect a sign: "We Have Come. Will You Build It?"

The collective image of a place is no easy beast to catch. Ask anyone who's lived here more than a week if there is a certain "Spokane Mentality" — if they think Spokane suffers from low self-esteem — and long-winded opinions are sure to follow.

Over mochas at Java City Espresso downtown, I put the question to owner Joe Nollette, 28, and one of his customers, a recent GU grad who is enjoying a leisurely summer before she begins an accounting job in town next month.

"How much time do I have?" Nollette wants to know, laughing. By the time we're sucking the syrup from the bottom of our drinks, the conversation's just beginning to cook. "There's the perception that there's a very conservative culture here, but it's not really that bad," Nollette says, "I know a lot of people who have taken off and tried to make money elsewhere, but now they're back. I think things are starting to change here.''

"I kept thinking I wanted to move to Portland," adds his customer, "but I had three job offers in town. I couldn't really turn that down. And I kind of like Spokane.'' A few blocks away, in the heart of the business district, another entrepreneur is banking on Spokane's changing face. Jim Franey, whose burrito joint Big Mamu opened on North Howard just six weeks ago, says he sees everything from suits and ties to dreadlocked teens in his shop.

A one-time car salesman, Franey's a friendly, bongo-playing cynic with a buzz cut and salt-and-pepper goatee. He spent years living in Boston and California's Bay Area, and the urban influence is obvious in his restaurant. Patrons can browse the latest editions of the Village Voice or The Rocket, listen to reggae, and dine on a very, very large burrito. It’s shops like his, Franey thinks, that will bring salvation-by-way-of-people to downtown.

"We need more places like this, more diversity" says the owner. “I’m optimistic. A lot of people come in and see what we've done here, and it inspires them.'' Franey's own inspiration came partly from seeing his next door neighbor, David's Pizza, do well. The block is a promising sight. Big Mamu has joined David's, a hip gift shop called Moon Shadow, and Brewhaha Espresso in an entrepreneurial block eager to bring some variety to the heart of downtown. "Spokane seemed ready for a place like [Big Mamu]. A generation has left and returned, and I think they've brought back a more cosmopolitan sensibility.”

W

hy are they coming back? Outside’s writer discovered the South Hill, and judging by his response, nearly stayed. "Get used to it, Spokane — you’re a babe ... Go up toward Manito Park and there it is," he writes, "an architecturally significant cutie-house reaching from the front yard with mature tree boughs and cooing, 'Come on in, honey.' The response, even if you've never been here before, is to fall down, weep, and swear you’ll never leave."Real estate agent Kathy Bixler sells these homes to the new arrivals — many from California, but a good handful from Seattle — who are arriving in Spokane in steadily increasing numbers. "I tell them they're 15 minutes from the airport and 10 from downtown, and that it's still in their price range. They stare at me in disbelief."

Bixler herself came here from Seattle in the '70s, long before the Emerald City became the destination for the terminally hip. She thought she wouldn't last a year. "Now I love it. I keep telling my kids to move back here." What she's seen over the last decade doesn't surprise her. "Back in 1985, people were leaving the area and moving to big cities. Now, I see the exact opposite. Everyone's coming back."

Between 1970 and 1990, Spokane's population grew from 170,516 to 177,196, or about 4 percent. Region-wide, this was a relatively slow influx of people. Eugene, Ore., for example, grew 40 percent over the same time span; Boise almost 50 percent. But in 1994, Spokane counted within its limits 185,600 heads, claiming in four years the amount of net growth it had seen in the last 20.

I can see it right out my window. From my duplex on the lower South Hill, I have views to the west and Northwest. Summer evenings, my girlfriend and I sit on the balcony and watch the sunlight fade behind the Selkirk foothills, while our hearts leap after it.

Our neighborhood is a mix of low and middle-income housing — it's populated mainly by young working adults and students. All but one of the buildings are turn-of-the-century homes now renovated into apartments or shared housing. By foot, we are 10 minutes from downtown, five to the neighborhood espresso shop or supermarket. Next door, a sign is advertising a vacant one-bedroom apartment for $280.

In Seattle, l paid the same amount to share a house with five others. From my bedroom, I had views of the highway and our neighbor's cement patio. My primary source of income came from refereeing soccer games, and I once had to hock my ski equipment to make rent.

Self-esteem, that sense of personal worth and respect in any given society, derives from a miasma of forces, but mostly it comes from what people say about you. In Latitudes and Attitudes: An Atlas of American Tastes, Trends, Politics, and Passions, Michael J. Weiss describes Spokane this way, "You won't find the yuppified tastes of cities like Seattle here in Eastern Washington: Spokane residents have relatively little interest in the arts, travel, health food, and high-tech electronics ... it is by no means a liberal bastion."

Compare this assessment with that of Seattle's, "Locals have the money to enjoy 'the good life': traveling abroad, enjoying gourmet cuisine — especially espresso ... The high concentration of young singles has even created a thriving grunge music scene, as well as busy jogging trails, fitness clubs, and nearby ski slopes."

And Portland's: "This is one of the nation's best markets for cultural sophisticates who enjoy photography, books, art, and theater ... everyone seems concerned about environmental threats, like nuclear waste and ozone depletion ... one of the nation's best cities for healthy skin."

Weiss' profiles are based on extensive survey's of media and product tastes — consumer maps, he calls them. This is the real America, Weiss claims in his introduction, a portrait of the country based on its most revealing behavior: consumption patterns.

Recently, the Spokesman-Review ran a brief story on the decision by Barnes and Noble (one of the country's largest booksellers) not to locate a new superstore in Spokane. The story failed to report what the decision was based on, but it's only natural to assume that market researchers for Barnes and Noble found that Spokane wouldn't support a store of that nature. True? Who knows. But Spokane's "reputation" may have something to do with these kinds of decisions.

What's often so difficult to accept about surveys like Weiss', and about market research in general, is that it tends to be self-perpetuating. A survey conducted in Hillyard may yield greatly different responses than one in Mead. What's real in American cities depends entirely upon which street corner you're standing on.

Take a look around. Chat with your neighbors. There is curious — maybe I should say conspicuous — evidence that Spokane is far from the buck-toothed, backwater place our coastal brethren (and some outside analysts) make it out to be. Counted the number of espresso huts around lately? Taken in a show at the Met, the Opera House, the Big Dipper or the Magic Lantern in the last month? Browsed the stacks at Auntie's? Seen a play?

Ralph Busch, outreach coordinator for the Spokane Arts Commission stresses the far-reaching importance of these places and activities. "The arts are like an octopus," he says. "They reach into all different aspects of our lives — social, political. economic." He also offers some very persuasive statistics on the level of interest and growth. An economic impact study of non-profit arts organizations in Spokane County conducted this year found about $6.5 million was pumped into the economy in 1990 from arts-related activity. By 1994, that figure had increased to almost $32 million.

Our skin may be dry, but contrary to the consumer maps, our cache of arts is not.

Not too long ago, I paid a visit to the west side. My girlfriend and I had been whining about the lack of live music in Spokane and went with the specific intent of seeing a band play at a club called Moe in Seattle's Capitol Hill district. We arrived to find about a hundred people milling near the doorway, several of whom came up to us to ask if we had tickets to sell. We didn't even have tickets for ourselves, nor did we ever get them. We spent the evening in a crowded bar across the street, looking out the window forlornly at the club.

On a similar evening in downtown Spokane, I see our cultural forces at work. A visiting guitarist has been playing at the El Toreador restaurant on Riverside. She's good — part Melissa Etheridge, part Indigo Girls. After her set, she is cornered by a man, a local, who forces her to listen to his demo tape. He tries to persuade her to sing backup on some project he's dreamt up. She's clearly uncomfortable with his perseverance, and eventually manages to slip away from the table and duck out of the restaurant. No one that I saw complimented her on her performance.

In a parking lot across the street is a car show — basically subwoofers on four wheels. People, mostly teenagers it seems, stand around, gawking.

One block away at Outback Jack's, a band is playing. Only one man is dancing to the group's medley of pop-punk songs. Every time someone else ventures onto the floor, usually young women, he tries to slam dance with them. But no one wants to stay out there with this lunatic flailing about. "Remember," shouts the lead singer. "This is supposed to be fun!"

Here's the surface energy of Spokane, the small eddies and currents of life after five. Tonight, nearly all the energy is concentrated in this one-block radius. Even the familiar line of automobiles cruising Riverside has been diverted to the car show. It's a peculiar, almost unidentifiable dynamic — far from the cosmopolitan spectacle of a larger city, yet still urban. And it's as awkward as watching a newborn calf take its feet, or watching kids out to dinner in their parents clothes.

In conversation after conversation, interview after interview, all dialogue leads back-to downtown — to the core.

"Downtown changed the minute NorthTown opened," says developer Ron Wells. "If Nordstrom and The Bon leave, the change will be [irreversible]."

Many stress the importance of some kind of mixed-income residential presence as a mainstay for downtown business. Wells believes this will take place on the fringe of the CBA, in areas like the Carnegie Square district, which his company has worked diligently to restore. "If you look at rehab districts in Seattle and Portland, you see them in areas adjacent to the primary business areas," Wells says. The potential here, he thinks, is tremendous.

Meri Berberet, the research and marketing director for Spokane's Economic Development Council, thinks we're beginning to tap some of it. The arrival of Egghead Software's corporate headquarters this year is exactly the kind of national attention the EDC wants to attract. That along with the arrival of Sallie Mae and the Principal Financial Group are good indicators that Spokane has caught the attention of healthy companies. And yet Money magazine ranks Spokane a dismal 232 out of 250 cities with the most promising investment potential. What does this mean?

The horizon is crowded with vision, theories, artists' sketches. Pick up a brochure for the new River Park Square and you'll find images of an unrecognizable city, a thousand people filing toward a glittering new mall in the sky, where hope, and shopping, springs eternal. Then wonder why, after all the existing shops have been kicked out, no one has yet committed to the project. Puzzle over a "pedestrian" mall that still invites automobile traffic to pass through. Scratch your head over a $25 million bus terminal that was built without any outdoor benches.

Were it up to me, I would place two books on the desk of every city council member, urban booster and local business leader in Spokane: The Urban West: Managing Growth and Decline by James B. Weatherby and Stephanie L. Witt; and New Visions for Metropolitan America by Anthony Downs.

The first is a lengthy and remarkable study conducted by two professors of public administration and political science at Boise State University. Refreshingly, The Urban West focuses on mid-sized, or "second tier" cities in the West, and often turns to Spokane as an example of westward urbanization, both pro and con.

New Visions is a more general portrait of urban America, concentrating on our desire for, and the implicit dangers of, low-density sprawl. America's dream of a house in the suburbs, a car, good schools and responsive local government has been realized in most places, but, says Downs, has created serious problems in the development of its cities: "traffic congestion, air pollution, loss of open space, higher taxes to pay for infrastructure, lack of affordable housing."

Both books explore the very complex phenomena called growth management. And both are acutely aware that growth management doesn't always fit comfortably in the same room as the democratic process. At the heart of both books, however, is the insistence that without the widespread participation of its people — not just its leaders, but also its citizens — growth in any given city will continue without a consistent direction until it collapses back in on itself.

On the worst days, I, too, want to move to Portland. So long, Loserville, thanks for nothing, I'd say, waving out my window as I speed west on 1-90. You can have your cutie house, Outside, give me a good bar and poetry slams.

But before I've even hit the highway, I'll hear that voice, the same one I hear when I walk past the Davenport Hotel, or peek inside the new lounge at the II Moon Cafe, the one that keeps saying, make it happen. I'll remember Ron Wells and Joe Nollette and Jim Franey and what they're doing, the budding sense of vitality and diversity they've brought. And it will remind me, once again, of what's possible here.

Published 8/23/95