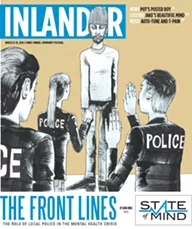

As community services and treatment programs for people with mental health issues have suffered cuts to funding, personnel and bed space, law enforcement officers have increasingly served as first responders to mental health crisis — sometimes leading to dangerous confrontations between police and the mentally ill.

We wrote last week about the local expansion of Crisis Intervention Team training to provide Spokane officers with new de-escalation skills and mental health awareness education to improve their ability to interact with people in mental health crisis.

But what might the next step look like?

In 2012, an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice found the Portland (Ore.) Police Bureau had a "pattern or practice" of using unreasonable force against people with mental illness. The Bureau later agreed to a settlement that required new training and policy safeguards regarding police force against people with mental health issues.

"We found instances that support a pattern of dangerous uses of force against persons who posed little or no threat and who could not, as a result of their mental illness, comply with officers' commands," a DOJ letter states. "We also found that PPB employs practices that escalate the use of force where there were clear earlier junctures when the force could have been avoided or minimized."

The bureau has spent the past two years trying to completely reform its approach to engaging people with mental health issues. PPB Lt. Cliff Bacigalupi tells the Inlander the DOJ findings gave the bureau the "political will" to reshape its approach to the mentally ill and drove the creation of the Behavioral Health Unit, which he now oversees. The centralized unit involves more than 50 specially trained officers.

"It hasn't been a pleasant thing," Bacigalupi says of the DOJ process, "but it's caused some very positive things."

As far as training, all Spokane officers have now completed an in-depth 40-hour course on crisis intervention. Portland, likewise, trains all officers through the initial course, but Bacigalupi says officers in the Behavioral Health Unit receive more than twice as much training, later completing a second 40-hour course on "enhanced" CIT.

Bacigalupi says the enhanced CIT training uses additional role-playing scenarios to strengthen de-escalation skills and also provides specialty training on suicide prevention, substance abuse risks, youth crisis or other mental health issues. The additional skills help officers diagnose issues more quickly and identify what sort of help a person needs.

"They can recognize when follow-up needs to be done," he says.

The Behavioral division also includes three Mobile Crisis Units that pair BHU officers with local mental health clinicians to make proactive visits to people who have repeated encounters with police. Clinicians can monitor whether a person is receiving stable treatment while officers get to meet with the mentally ill at a time when they're not actively suffering a psychotic episode or other crisis. This video offers a brief glimpse:

Spokane Police Chief Frank Straub, who recently praised the reforms underway in Portland, says he plans to "ramp up" mental health outreach, training and community partnerships in the coming years. Looking at Portland's mobile unit, Straub notes he developed a similar effort with mental health professionals when he led the police department in White Plains, N.Y.

"In White Plains, we identified all the high-end users of police and mental health services," he says. "We literally had a list and this team would regularly go through the list."

Officers and mental health specialists would perform regular "welfare checks" on high-risk individuals to monitor their medications, mental health appointments and other services. Keeping people on stable treatment helped prevent them from lapsing into crisis. Straub says he would like to establish a similar effort in Spokane.

"What we found was we were able to reduce the police calls for service somewhat significantly because we weren't sending radio cars to people who had now gone into crisis," he says. "That was a big benefit. We were also, at the end of the day, able to reduce medical costs because if you keep someone on a maintenance program, you don't have these big swings [in mood or mental stability]."

Straub says he may also adopt some crisis intervention strategies from the New York Police Department (where he once worked) and the Los Angeles Police Department. Both departments also have special teams that respond to mental health incidents and receive additional training in the use of less-lethal force devices like police riot shields or bean-bag guns.

"Probably within the next two or three months," he says, "I'll start sending some of our officers who have an interest in this to other jurisdictions to see how they deal with persons in crisis."

The Portland program goes further than many jurisdictions, but some community members have continued to criticize the reforms as insufficient. Bacigalupi says the Behavioral Health Unit has spent much of the last year trying to track data on police encounters with the mentally ill along with dispatch calls and outcomes. But while they have collected many anecdotal success stories, it remains difficult to measure the total impact.

"Our ultimate product is the event that never takes place," he says.

Bacigalupi — like Straub and many mental health experts — argues the best way to prevent tragic encounters between law enforcement and people with mental illness is to make sure community-based mental health treatment services have the necessary resources to properly treat and stabilize people at risk of crisis.

"The success or failure of these units, by and large," he says, "will depend on the buy-in you get from the community."