For four years, Doctor Who has been pure fan fiction.

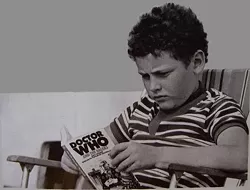

That’s not a pejorative, it’s simply an accurate description: The show’s current showrunner, Steven Moffat, was once a little chubby curly-haired kid watching the old Doctor Who series and reading Doctor Who paperbacks.

And, in a fairy-tale happy ending, that little boy grew up and took reins of the show he loved so much.

Doctor Who, if you haven’t heard, is a show about a zany British-accented Time Lord, who takes his “companions” (usually an attractive female) on all sorts of adventures. Moffat, a writer on the show (and writer of the Emmy Award-winning Sherlock) replaced Russell T. Davies as Doctor Who’s head showrunner in 2010. Most people were excited. After all, Moffat had written some of the show’s best episodes.

But in the last few years, Moffat’s come under fire for what they see as a decline of Doctor Who. Critics say he’s sexist, that he’s too obsessed with puzzle-box plotting, that he hits his themes too often, that he’s made the show too big and too messy.

Taken individually, many of the points they make are good ones, but in trying to say that Moffat has hurt the show as a whole, they seem to forget how many awful moments there were during the Davies era. The worst, worst, worst of Doctor Who came under Davies: The two-parter with the farting aliens? Written by Davies. The terrible episode that ends with the implication of a character getting oral sex from a paving stone? Written by Davies. And while he didn’t write it, he pushed the main plot-points for “Fear Her,” the cringe-worthy episode with drawings that come alive.

Moffat’s seasons have been uneven, sure: But never so bad as Davies’ worst moments.

By contrast, nearly every great episode from the Davies era was written by Moffat. He was the one coming up with all the best ideas: Carnivorous shadows. Stone angels that murder by touch, but only move when you blink. A medical nanobot swarm that re-forms human faces into the visages of gas masks. In fact, sometimes Moffat’s weakness is too many good ideas. He tries to shove a dozen sci-fi concepts into single episodes and crowds out the impact of any of them. Even when Moffat became showrunner, he delivered, by far, the best Christmas serial of the modern era, using time-travel as an elegant way to deconstruct and reimagine Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Even the weakest episodes of his tenure have had great moments.

Look at this beautiful monologue, where The Doctor tells off a God the size of a sun, or this one, where he sums up the whole show by unreeling the scope and danger of the universe to a beleaguered dad. Both are from mediocre episodes (written by other writers during Moffat’s run) but they contain some of my favorite scenes.

Frankly, Moffat is just more creative. Davies relied on pure unimaginative scale to create stakes in his season finales, flooding Earth with a thousand Daleks or a million Cybermen, or a million Toclafane. Davies created impossible situations then easily resolved them with a magical button press, a flurry of techno-babble, or the gauzy power of love.

Moffat, for the most part, went a far more complicated route: He plants the seeds of the villains’ defeats in his finales far before he even faces them. The success of this tactic has been uneven, but it’s far more ambitious and fascinating than anything his predecessor attempted. Even the chaos and frantic nature of the show feel like they reflect the character of the show’s central figure.

Doctor Who is a show about the wonder and terror of time as well the wonder and terror of space. Moffat understands that, using time travel as a tool to explore the horror of old age and loneliness, to examine the redemptive power, not of love, but of memory. That’s a rabbit hole worthy of exploring.

One accusation does seem valid: His major female characters — River Song, Amy Pond, Clara Oswald — all feel cut from the same cloth. Remove the actresses performances from the equation and the writing for them often feels identical.

But Moffat’s writing of his companions, flirtatious and prone to sexually-charged banter, seem far less sexist than Davies’ writing of Rose Tyler, the companion who spent much of her time desperately mooning over the doctor. Some critics have accused Moffat’s female characters of too often playing damsels in distress. But Pond is much more assertive and foregrounded than her husband. Both Pond and her husband are damsels in distress at times, yet both get to be the shiny-armored knights riding to the other’s rescue.

Moffat is an uneven writer, sure. But Doctor Who has always been a wonderfully uneven show, all the way back in the days of black-and-white monsters with visible zippers.