Hunchbacked fins by the hundreds once cut the churning surface of a free-flowing, unspoiled Spokane River, its waters teeming with silvery chinook salmon for the legendary summer spawning runs of the late 19th century. As many as 1,000 salmon a day fell to the spears and traps of the Spokane Indians and other regional tribes. For generations, families and wildlife fed off the bounty. The river brought salmon, and the salmon brought life.

Cold and quiet, those same waters seem almost sterile today as Jerry White, the recently hired Spokane Riverkeeper, hikes down to a rocky shoreline near the Maple Street Bridge. White, 51, wears a ballcap and cargo shorts. Surveying the soft current, he smiles wide.

"When I look at the river, it's a lot like looking at the stars," White says. "It's very vast and a very powerful place where a lot of different things come together."

Spokane's river isn't dead. For White and others still tied into the iconic waterway, the truth remains much more complicated than that — but also more hopeful. In 100 years, the Spokane River has transformed from sacred ground to sewage dump to the region's resilient mascot. Civilization has suffocated it. Industry has dammed it, poisoned it. Neighbors have forsaken it. Still it flows.

A longtime fish conservationist, White took over in July as Riverkeeper, a Spokane-focused water quality advocate with the nonprofit Center for Justice. He has since traveled up and down the river, exploring its injuries and innovations. In early September, a handful of city and tribal officials gather for a tour. Together, they help White drag a blue rubber raft to the water's edge.

Claiming his seat between the oars, White leans into each stroke. Society has changed as well, he explains. The river now has more champions than ever as environmentalists and government agencies partner to monitor toxins and protect water flows. Many public officials now debate chemical discharges, fish consumption rates, stormwater mitigation and agricultural runoff.

But beyond that, this fall marks the first reworking of the Columbia River Treaty in 50 years, opening up a previously undreamt possibility for wild salmon to one day return to Spokane's waters.

"At the end of the day, it's a value judgement," White says. "It's kind of up to the culture to decide what they want to have in a river... What is a river?"

Forged more than 15,000 years ago in the cataclysm of the Missoula Floods — a time when glacial dams repeatedly burst, spilling untold oceans over Eastern Washington — the relatively young Spokane River Basin covers about 6,000 square miles from the Bitterroot Mountains to the Columbia River. The river itself emerges as a wide outlet of Cougar Bay in the northwest corner of Lake Coeur d'Alene, running 111 miles through Post Falls, Spokane Valley and the heart of Spokane before continuing west to Lake Roosevelt.

Native lore holds that the mythical Coyote created Spokane's waterfalls in a fit of unloved vengeance, smashing the basalt and spray with his immense paw to block salmon from reaching the upriver tribes he felt had wronged him. Washington Water Power, now known as Avista, took over from there.

Regional tribes gathered along its banks for centuries, often fishing, trading and communing with their neighbors. European traders and settlers appeared in the early 1800s, and in 1873 Spokane founder James Glover first set eyes on the Inland Empire, spending an entire night staring at the falls as its spray soaked his hair and clothing.

So "enchanted" was Glover with its cascading that he determined then and there to possess the falls and anchor his legacy in its allure. He would later incorporate the city of Spokane Falls, reborn as Spokane after the Great Fire of 1889. Washington Water Power would form that same year. Mills and railroads soon crowded in along the banks, launching an unprecedented age of abuse.

For decades, human sewage, mill sawdust and laundry solvents flushed into the city's river. In The Fair and the Falls, historian J. William T. Youngs writes that officials boasted of how conveniently the river washed trash downstream and out of the city. They built dump ramps directly into the river, even as citizens became increasingly suspicious of the sometimes foul-tasting drinking water.

Spokane later worked hard to remake its image as it prepared for the 1974 World's Fair, carving out Riverfront Park and uniting behind a theme of environmental protection. With the historic salmon long gone, Youngs writes that Expo '74 organizers hoped to prove the Spokane River's renewed health by dumping 1,974 trout into its waters during the fair's Opening Day ceremony.

Unfortunately, Expo's vice president of operations later admitted, most of the just-released fish swam directly into a nearby Washington Water Power turbine and died.

"Lost all of them," he told Youngs. "We didn't say anything about that."

Paddling past the willows and cottonwoods of the lower Spokane River, White nods with approval. Sunlight shines down on the shallow water, kicking up blue and golden ripples. The current bobs and slips softly as White rotates the raft sideways to offer a view backward at the city skyline.

"I enjoy this vista," he says. "It's just kind of cool to see our city from here."

White remembers attending Expo '74 as a boy. He can still picture the bright algae choking the river edges, a sign of the high amounts of sewage and phosphorus pouring into the river. Growing up, he often fished and hunted along its banks. He considers himself lucky to serve the river he loves.

"It all seems sort of natural," he says. "I feel privileged to be able to work on behalf of the river and the people this way."

White first learned to love the water through a love of fishing. His grandfather often took him salmon fishing on the Willamette River as a boy in Oregon. He later moved to Cheney, eventually studying archaeology. He spent several years working in cultural preservation across the state and then teaching before joining the staff of the Save Our Wild Salmon fish conservation group in 2008.

For a time, White returned to teaching while also volunteering with the Spokane Falls chapter of Trout Unlimited. He now lives in West Central, a short walk from the water, and jumped at the Riverkeeper position when it came open this summer. White serves as the city's third Riverkeeper since the Center for Justice introduced the position in 2009.

White has since spent the past two months making introductions and seeking input on the many issues facing the river. His passengers in the raft today represent a handful of prominent stakeholders in the ongoing health of the region's watershed.

Matt Wynne, with the Spokane Tribe of Indians, lounges against the front of the raft and soaks in the afternoon sun. As chairman of the Upper Columbia United Tribes, Wynne advocates for five regional tribes on the management of land and waterways along the Columbia River, including the long struggle to get salmon over the Grand Coulee Dam and back into the river's northern reaches.

In back, wearing sunglasses and a sly grin, sits Brian Crossley, one leg lazily slung overboard, dragging in the water. As the Spokane Tribe's water and fish program manager, he has overseen the tribe's surface water quality monitoring for 15 years.

Next to Crossley rests Spokane Utilities Director Rick Romero, the administrative mastermind behind the city's recently adopted Integrated Clean Water Plan — a $310 million effort to reshape how city departments work together to improve wastewater storage and treatment over the next 20 years.

Everyone seems pretty smug about getting to spend the afternoon rafting. White has always admired how the river brings people together, whether it's anglers, children splashing in the shallows or dozens of drunks floating on inner tubes.

"All of [these] communities draw a lot of identity from the river," he says. "We work in the river. We play in the river. ... It's an economic, social and psychic resource that all the communities along the river rely on in various ways."

Attention snaps to the left side of the raft as Crossley points below the surface, the flash of a silver tail quickly darting out of sight.

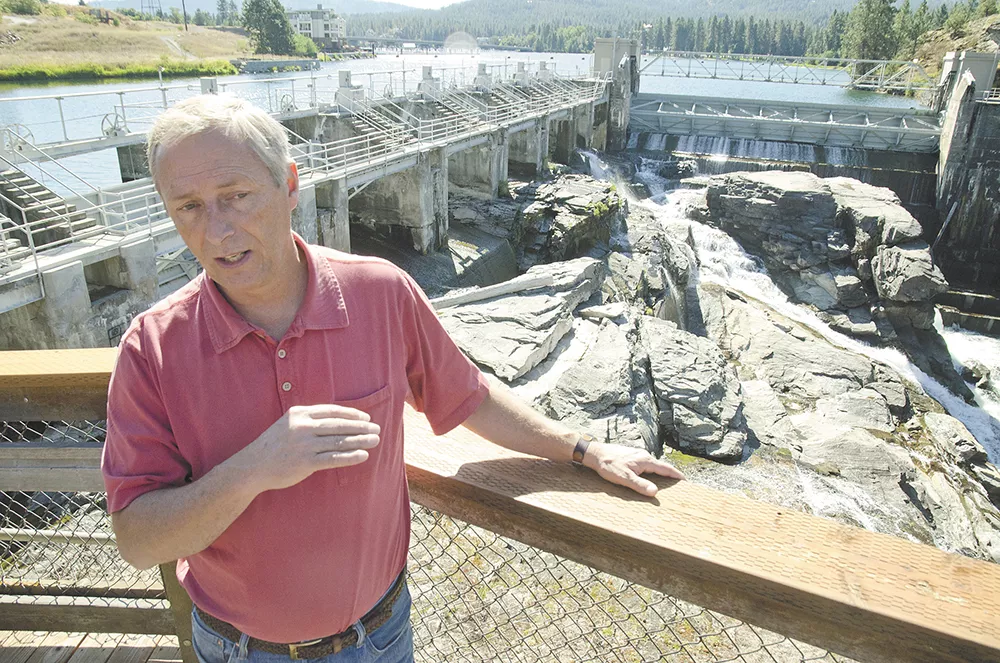

Earlier in the morning, before the rafting trip, White arrives at the Post Falls Dam in a dark green VW EuroVan. Bumper stickers plaster the back end, reading "I'm Pro-Salmon and I vote!" and "I [heart] the Spokane River." Little more than a trickle of water spills through the 108-year-old dam as Pat Maher with Avista explains that the company recently increased water flows according to a seasonal schedule.

"About half of the year, Avista's actually controlling the level of [Lake Coeur d'Alene] and about half of the year it's as if this dam wasn't even here," says Maher, Avista's senior hydro operations engineer. "This is a really unique situation where you've got the 9 miles of river between the dam and the lake."

As the Coeur d'Alene, St. Joe, St. Maries and other rivers all feed into Lake Coeur d'Alene, the Spokane River drains out of a natural outlet down to where it meets Avista's three sections of the Post Falls Dam. That dam complex often allows water to simply pass through, but it can trap water to keep the lake stable and generate power through the turbines.

Historically, Avista has faced criticism over extreme changes to water flow that often either blew out the Spokane River or left it dry. In 2009, the Spokane-based utility company received a new license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission that establishes minimum flow levels and requires additional habitat mitigation.

Advocates acknowledge that the increased flow levels have had positive impacts, but they hope ongoing studies can clarify whether higher flows are needed. The Washington Department of Ecology last month proposed new flow requirements and continues to accept public comment on the issue.

Speed Fitzhugh, Avista's Spokane River license manager, says the utility is halfway through a 10-year study on spawning habitats. He notes the company also has a number of habitat restoration and recreational access projects underway throughout its five dam facilities and thousands of acres of property in Washington and Idaho. He points to the south section of the Post Falls Dam where construction crews are now working to install computer-operated spillway gates.

"There's a lot going on in the system," he says. "We have wetland projects, fishery projects, erosion control, water quality, recreation, land use, bald eagle management. We pretty much cover the full gamut."

As the silver tail disappears into the subsurface shadows, the Riverkeeper raft crosses over the once mighty spawning pools of the last century's salmon. Wynne says the Spokane Tribe used to have more than 20 fishing camps scattered along the river, stretching from Spokane Valley out past Long Lake. Salmon served as a primary staple of diet and trade, bringing families together for harvests, games and feasts each summer.

"It's been 75 years since the last salmon came up to our territory," Wynne says.

Long Lake Dam erected the first major obstacle to salmon migration when it went up 30 miles northwest of Spokane in 1915. But it was the completion of the massive Grand Coulee Dam in 1942 that finally extirpated, or permanently blocked, salmon from the Spokane River and other northern tributaries.

In 1964, the United States and Canada enacted the Columbia River Treaty, a 50-year agreement on the management of Columbia River flows and volumes shared between the two nations. Regional tribes had no say in the agreement, which failed to include protections for habitat or fish passage.

Crossley explains tribes have since won rights to hatchery salmon for modern food and ceremony, but the social and economic value of the local fisheries has disappeared. While lower stretches of the Columbia and Snake rivers draw thousands of salmon anglers each year, the Spokane River continues to suffer.

"We replaced the fish with other things," he says of dams, development and industry. "It's a travesty on man's part."

Local conservationists note the Spokane River still serves as important habitat for native redband trout, a genetically unique variety of rainbow trout with a distinct red stripe along its side. The waterway also provides a valuable corridor for wildlife to pass through urban development, sheltering deer, beaver, skunk and even moose in pockets of riverside forest within the city limits.

But bringing back salmon, which spawn annually and die to leave behind huge nutritional bounties, could foster a renaissance in ecosystem vitality.

In the years since the Columbia River Treaty, environmental priorities have shifted dramatically. Wynne says a new momentum has gathered around fish passage as other regional tribes have fought for fish ladders or even the removal of dams such as the Glines Canyon Dam in Olympic National Park earlier this year.

Wynne has traveled across the state to see Baker Dam, a 285-foot structure where Puget Sound Energy's fish restoration efforts have increased salmon returns from just 99 fish in 1985 to more than 48,000 in 2012. He argues the technology has proven successful.

With the renegotiation of the Columbia River Treaty scheduled to begin this fall, Wynne sees an unprecedented chance to include salmon passage and other ecosystem-based mandates in the operation of Grand Coulee Dam as well as Chief Joseph Dam, which lies about 50 miles downstream.

If salmon get over Grand Coulee, fish could start repopulating the Spokane River within a generation.

"For the first time ever — ever," Wynne tells White, "they talk about reintroduction. The first time in history."

"Ten years ago, if you had brought up [salmon] coming back here," White says, turning to the river, "people would have given you a tinfoil hat."

Across an entire wall at the Spokane County Water Reclamation Center hangs an immense map of the Inland Northwest with a detailed outline of the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer, a 322-square-mile underground reserve that provides most of the drinking water for the region. Estimates put the aquifer's total volume at about 10 trillion gallons.

County Water Resources Manager Rob Lindsay says protecting the aquifer serves as the foundation for all of the county's water quality efforts — the greatest of which has been the opening of the new reclamation center in late 2011. The $173 million facility cost more than any other capital project in the history of Spokane County.

"Is it about the river? Yes," he says, "but it's even more about the aquifer."

Water constantly crosses back and forth between the aquifer and the Spokane River. In some areas the river drains into the aquifer, while in other reaches the aquifer charges water up into the river. Those recharged stretches often carry noticeably colder water, which provides better conditions for fish.

County Reclamation Manager Dave Moss says the county center now treats about 2.5 billion gallons of sewage each year, running it through aeration, settling tanks and microfilters.

"People put lots of funny things down the drain," he says with a chuckle. "We get little cars. We get cell phones. We get reading glasses. Anything that's intentionally or inadvertently flushed down the toilet."

Treatment removes solids along with all but the most minute amounts of heavy metals, nitrates, phosphorus and PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, linked to increased risk of cancer and reduced birth weights. Moss says PCBs come into the plant at about 15,000 parts per quadrillion.

"We treat them down to almost zero," he says. "We're talking 100-ish [parts per quadrillion]."

A state pollution control hearings board invalidated part of the plant's discharge permit last year following a complaint from the Sierra Club that PCB limits lacked clarity. Lindsay says the county has appealed that decision and continues to operate under its previously issued permit.

Stormwater does not go through the reclamation system, but the county has recently ramped up a septic tank replacement program to decrease the amount of sewage draining into the aquifer. Lindsay explains that linking those homes into the treatment process prevents additional strain on the natural water system.

"Our ethic today on water quality is different than it was five years ago," he notes. "We know more."

Drifting downriver toward People's Park, Romero takes note of rusted pipes jutting into the river as part of the city's discharge system. The City of Spokane maintains 871 miles of sewage pipe, including 20 controversial "combined sewer outflows," commonly called CSO pipes. During heavy rains, stormwater runoff can sometimes overwhelm the city's water treatment system and flush raw sewage out those pipes into the river.

"We have jurisdiction on anything we discharge," says Romero, who took over the city Public Works and Utilities Division in 2012. "We're responsible for assuring the cleanup of anything between our boundaries."

City leaders first warned of industrial pollution in the Spokane River as early as 1882, when The Spokan Times suggested mill sawdust was killing fish, historian Youngs writes. Economic interests quickly smothered those concerns, and industry spent the next several decades pumping dangerous levels of phosphorus, zinc, bacteria and other harmful pollutants into the river.

The city now treats wastewater in accordance with the federal Clean Water Act as well as a number of state provisions, including a TMDL (Total Maximum Daily Load) order on phosphorus and dissolved oxygen. Many recent city efforts have also targeted PCBs, including a June city council ordinance against purchasing any items that contain the toxin.

For the past two years, Romero has led an effort to reshape the city's Integrated Clean Water Plan to address a broader range of pollutants, while upgrading water treatment facilities faster and for less money. He says the $310 million plan also commits the city to replacing outdated stormwater networks in conjunction with street repairs, reducing redundant expenses over the next 20 years.

"You're looking three-dimensionally instead of just two-dimensionally," he says.

Romero explains that most government agencies focus on one pollutant at a time, spending millions of dollars to treat 100 percent of a single toxin. He says the new integrated plan takes a more holistic approach, aiming for just 99.6 percent of CSO output, but saving enough on that last half of a percent to invest in facilities that treat a wider range of toxins.

"It's trying to balance what we have to do with what we should do," he says, noting, "Probably what we should do is going to be what we have to do eventually."

About $107 million of the plan would go toward outfitting the city's Riverside Park Water Reclamation Facility with a new membrane filtration system to remove higher levels of phosphorus and other toxins. The rest pays for increasing CSO treatment storage and capacity as well as modernizing the stormwater system.

State officials have praised the plan as innovative and ambitious; the city plans to ask the Legislature to contribute $60 million to the project. Voters will also get a say on the November street levy, which provides funding for water upgrades tied into future street repair projects.

"We believe it's the right thing to do," Romero says, "and we believe it's certainly best for the citizens' pocketbook."

White pulls the raft into shore at the mouth of Latah Creek, also known as Hangman, a troubled drainage stretching from Idaho down through the agricultural fields of the Palouse before dumping into the Spokane River at People's Park. While fish spawn nearby and great blue herons soar overhead, the creek's warm, muddy waters continue to pose a stubborn threat to the river system.

"This is sadly a very polluted body of water," White says. "It's good to keep in mind that salmon came up this creek. ... Now, it's so degraded."

"They didn't go real far," Wynne notes, "but they did go up there."

Phosphorus and nitrogen-heavy runoff from farm fields have flooded the creek system with excessive nutrients, which lead to an overabundance of algae, invasive weed growth and low oxygen levels. Extreme erosion also fills the watershed with sediment, leaving South Hill homes precariously perched on disappearing hillsides while sand buildup buries spawning habitat.

On a recent trip up the Latah Creek watershed, White points out stagnant pools filled with algae. In some pastures, cattle graze along the banks, sometimes defecating into the stream. Many sections of the creek have been redirected into straight ditches that collect runoff from fields.

Dust billowed in the air as farmers plowed up their land for the fall. Despite new techniques that protect against erosion, many older farmers still till their fields each year, allowing soil and fertilizer to blow or wash into the creek.

Several conservation groups now work throughout the watershed to restore and protect habitat. Trout Unlimited has supported a "Willow Warriors" project that floats down the creek planting willow trees to slow erosion and increase habitat. The Lands Council also conducts a beaver protection program because the animals contribute to natural wetlands.

In the distant Idaho reaches of the upper watershed, the Coeur d'Alene Tribe has redirected the creek from man-made ditches back into its natural drainages. Early results have shown the creek and wildlife quickly reclaiming the old waterways.

Romero notes the integrated water plan will remove the city's last CSO pipe from Latah Creek as a part of the ongoing High Drive street repairs.

"Getting anything out of that tributary is a pretty big deal," he says.

Some of the challenges facing Latah Creek demonstrate the importance of protecting cold, clear river habitat that could one day support salmon, Crossley explains. Taking on the problems with Latah Creek make for a stronger Spokane River system that could support larger fish.

As the blue raft starts down the river again, a glance into the water shows submerged rocks fuzzy and brown with fresh algae.

Pulling off the water near the former site of Natatorium Park at the west end of Boone, the rafters lift a cooler onto shore and settle in for lunch. Everyone loosens their life jackets as they crack open Cokes. White hands out rolls with salami and cheese. All along the river, signs warn anglers to limit how much fish they eat from the Spokane River due to the level of PCBs, heavy metals and other toxins. In some sections, they suggest none because the more fish people eat, the more they risk exposure to those toxins.

Washington currently sets water standards based on a "fish consumption rate" of 6.5 grams a day, about a pinky finger-sized portion. Northwest tribes, which often rely on fish-heavy diets, argue the current rates underestimate actual intake by up to tenfold. Crossley says the tribe has long pushed for the state to adopt a rate that more accurately represents historic tribal diets.

"They never have been realistic," Crossley says of current rates. "We consumed a whole lot more than that."

Gov. Jay Inslee earlier this year proposed increasing the state's fish consumption rate to 175 grams a day, a figure considered much more realistic. But the proposal would also increase the allowable cancer risk rate from one in 1 million to one in 100,000, undermining in many eyes any actual improvement in safety standards.

The Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission opposes the governor's new proposal. The Sierra Club, along with other environmental advocates including Spokane Riverkeeper, previously filed a lawsuit to push the Environmental Protection Agency to enforce PCB protections at the federal level. In a July hearing, an advocacy attorney described the Spokane River as the "worst PCB contamination problem of any river in the state."

A U.S. District judge earlier this month dismissed that case, ruling the EPA had not made a determination on consumption rates, so it could not be ordered to enforce them under the current circumstances.

Boeing, as well as Inland Empire Paper locally, have voiced concerns about increasing state water quality standards to levels they argue would prove prohibitively expensive. The state Department of Ecology continues to work on language for any new standards. Ecology officials previously promised to release draft rules by this week. (Update: Now released.)

White says tribal officials have taken the lead on this issue, but he emphasizes the new rates impact any communities with significant amounts of fish in their diets.

After lunch, Crossley finds a blue-tinted heron feather on the shore and affixes it to the tail end of the raft, a tiny flag of good fortune. Drifting around the next bend, White soon spots a hunk of rusted metal discarded at the water's edge. Squinting to make it out, he laughs and shakes his head.

"Anybody need an engine block?" he asks.

Nearing the end of the trip at the TJ Meenach Bridge, the group has spent nearly four hours sharing fond stories and bold hopes for the future of the river. A bit reluctant to leave the quiet peace of the river, they dutifully haul the raft up onshore and load it onto a trailer. White takes notice of the heron feather sticking up from the rear of the unnamed raft.

"Blue Heron," he says. "I think we might have just found a name."

Everyone leaves with a renewed sense of purpose. Romero says the trip served as an important reminder of why the city must invest in a healthy, clean river, so residents can enjoy its water for years to come. Crossley finds encouragement in the efforts that have already dramatically improved habitat that could one day welcome back salmon.

Wynne sees momentum for salmon recovery continuing to build. The river may never again see the mesmerizing throngs of fins along its surface, but the occasional flash of a chinook torpedoing by would be a primal thrill, and a small righting of historic wrongs.

"I won't stop," he says. "I'll never stop talking salmon."

When White looks out at the Spokane River, he sees all of these layers upon layers, with many new challenges hidden beneath the surface. Memories mix with dreams and ambitions. They won't happen overnight, but many have already started coming true.

"It really is about falling in love with a place and taking care of it," he says. "When you have that kind of profound connection, that's when you can really start thinking, generations down the road, of what this river might mean ... not just what dollars it can turn for you right now." ♦