Night-black water lapped at the banks of the Spokane River just west of the Monroe Street Bridge while helicopter blades beat against the sky overhead. They were looking for a person. Or maybe a body. But they found nothing.

That was about 18 hours after Suzan Marshall got a call. Her husband, John, chief of surgery at the veterans hospital in Spokane, hadn't shown up for work.

"Bad, bad, bad," she says of her initial reaction. The kids were already at school. She drove to the YMCA on North Monroe where her husband exercised most mornings. His car was still in the parking lot, coffee mug in the cup holder, his gym bag still in the gym cubbyhole.

For about six hours, with the help of friends and family, Suzan Marshall had searched the area; they thought he might be alive. By nightfall, she had to pick her kids up from piano lessons. Before bed that night, she told them, "We just need to find Daddy. We can deal with whatever happens when we get there. We just need to find him."

His body was found early the next morning on Jan. 26, floating in shallow water on the north bank of the Spokane River, just west of the Monroe Street Bridge — one spot where his wife says she looked the day before. She stood with her children and watched as first responders pulled John's body from the water. Media crews flocked to the Centennial Trail. Passersby pointed cellphones at the water. Suzan Marshall's mind turned with questions.

It's been three months since his body was found. The medical examiner ruled the cause of death was drowning, an accident. Police have suspended the investigation, meaning they could reopen the case if new information emerges, but they're no longer actively chasing down leads. No one has offered any further explanation, Suzan Marshall says.

She's since hired a private investigator, who says his efforts are being "stonewalled" by the Spokane Police Department's refusal to share its investigation immediately.

"There's pain and treachery," Suzan Marshall says. "Did someone do this to him? And how did he get into the water? Finding closure and acceptance is that much more difficult."

WHAT WE KNOW

Spokane police started looking for him around 4 pm on Jan. 25, by his wife's recollection. To Suzan Marshall's surprise, police typically don't actively search for reportedly missing adults unless the person is in danger because of a mental or physical disability, says Spokane Police Officer Teresa Fuller.

Approaching midnight, a helicopter scanning the river found nothing. By 8 am Tuesday, joggers spotted a body floating in the shallow water near the bridge. The police confirmed the body was the "missing VA surgeon."

Ted Pulver, Suzan Marshall's private investigator, is pursuing at least one theory that John Marshall entered the river from the plaza just below City Hall. Since he was found fully clothed, and with his shoes and socks on and his iPod in his pocket, Pulver believes it is highly unlikely that John Marshall fell through the falls. He is also puzzled how the river's currents could have left the body in such shallow water.

"The water level should not have allowed the body to be there," he says. "I've talked with the hydrologist and the staff at Avista, and they could not come up with a scenario that the body would have been there."

Injuries reported in the autopsy point to the likelihood of an assault, according to Suzan Marshall, who also is a surgeon.

She says she's already shelled out $5,000 for the private investigation (and has set up a fundraising page on GoFundMe.com), but Pulver says his efforts have stalled because Spokane police are not willing to share unredacted copies of their investigation.

"Time is your enemy on investigations of this type," Pulver says. "Every hour that goes by makes it that much more difficult. It's been over 30 days since [the police suspended the investigation] and for whatever reason we haven't received one page of information."

Spokane police say they are in the process of redacting information and will release the investigation when that process is complete. The Inlander made an identical request and was told it would take at least 100 business days to complete.

'COSMICALLY CONNECTED'

The night before John Marshall went missing, his wife recalls that he fell asleep holding her hand. She was babbling about "our incredible romance 20 years earlier, like we so often did."

All their photos are in albums because he put them there, his wife says. He signed up to run in the Bloomsday race with his son months ago, a commitment the 13-year-old intends to keep. And when he missed the father-daughter Valentine's Day dance in February, his brother stepped in to take his 10-year-old daughter.

Sometimes, after the kids were in bed, Suzan Marshall says they would stroll into the pasture on their 25-acre property with a glass of wine and look up at the stars.

"We made it," John Marshall would say.

"John and I were so incredibly cosmically connected. I do feel like a part of me died," Suzan Marshall says now.

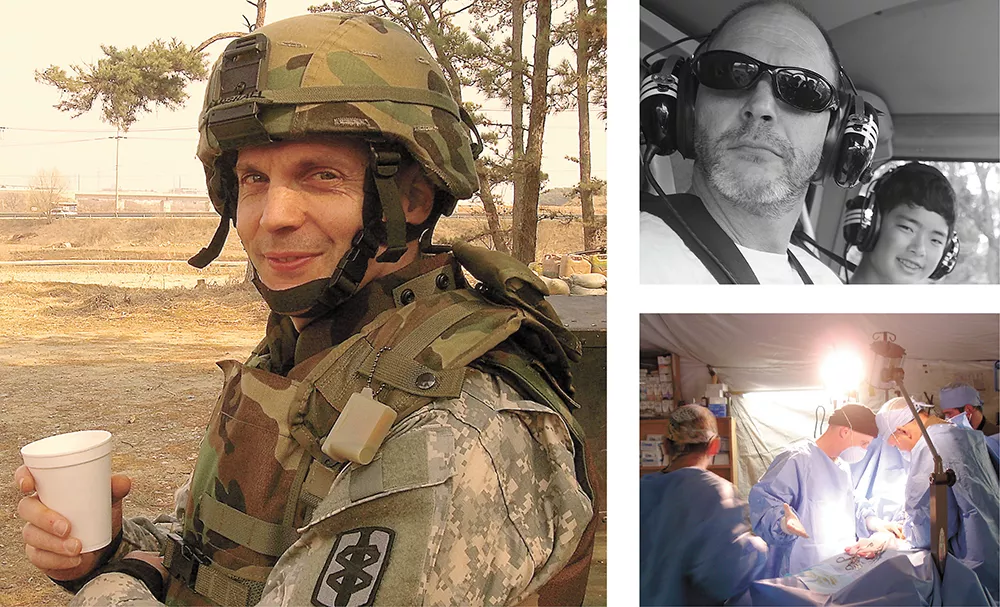

Occasionally the former Marine Corps and Army officer would surprise his family with vacations, not telling them where they were going until they got there. They would do the same for him. His wife planned to take him to Hawaii for his upcoming 50th birthday. Instead, that was the day she cremated him. Her hand trembled as she pushed the button to start the incinerator.

WHAT HASN'T CHANGED

John Marshall's clothes are still hanging in his closet, his toothbrush still in the bathroom he shared with his wife. Hanging above the couple's tub is Howard Pyle's painting The Mermaid.

As the story goes, one of Pyle's students found the painting sitting on an easel in his studio. Pyle died before he could finish it, but the painting depicts a mermaid lifting a man out of a briny, blue-green sea.

"It's this idea of two worlds that can never be together again," Suzan Marshall says. "But that doesn't mean they can't affect and inspire each other."

The print held poignant significance for her the night she returned from searching the river. A military veteran herself, Suzan Marshall doesn't typically cry over her husband in front of people — at least not anymore. But she did that night.

Suzan Marshall says as long as the word "accident" remains the official determination without further explanation, she can't have closure. She owes it to her husband. Indeed, when she recently fractured her left hand, she simply moved her diamond engagement and anniversary rings to her right.

"I'm still married in my heart," she says. "It doesn't change." ♦