Lacey Hendrix never told attorney Craig Swapp about the accident. She'd never met him. He was just a name on TV.

It happened two years ago this week. She was riding her friend's purple bike on a sidewalk, carrying the socks she picked up for her Burger King job in her backpack, when a car came out of nowhere. Either the hedges were too tall or the driver didn't bother to look: He slammed into her hard. The car flung her into the lane, mangled the bike, cracked a bone in her upper arm.

The guy who hit her, she says, never even bothered to check on her. She told her family, a few friends, the cops and Burger King. But she mostly kept it quiet. She didn't even post about it on Facebook.

But Craig Swapp knew. He knew so quickly that only four days later, he sent her a letter in the mail.

"I fully understand the challenges you may be facing as you hope to regain your health, while struggling with the high costs of the accident," Swapp wrote her. "We'd like to help."

It was the first piece of mail she got about the accident, and it was from some random lawyer.

"Like, who the f--- is this?" Hendrix recalls thinking.

The letter outlined a parade of horrors Hendrix might experience — "medical bills, lost income, pain and suffering, physical limitations and scars" — but posed the possibility of "full compensation" for all of it, even for future medical costs.

Swapp's big pitch was highlighted in bold: "You have everything to gain and nothing to lose by calling us right away. The faster you call, the faster we can build a strong case for you."

And just to make things easier for her, he enclosed the police report for the accident.

"My very first reaction was they're just trying to help. Then I'm like, 'But wait a second.' It just felt wrong," Hendrix says. "How does my information get out there so fast? Do they just have somebody who is looking for new police reports so they can prey on someone who just got hit by a car?"

Swapp's letter was upfront about it: He used Washington state's public records law. The same law journalists use to expose corruption, hypocrisy and cover-ups is the same law many attorneys, chiropractors and advertising agencies use to find clients.

When she showed the letter to her dad, he was ticked off.

"I've got very little respect for any attorney," says Dan Hendrix, who particularly takes issue with the kind of attorneys who scramble to contact victims directly after a tragedy and sell them their legal services. "I find it offensive. They're ambulance chasers and scumbags."

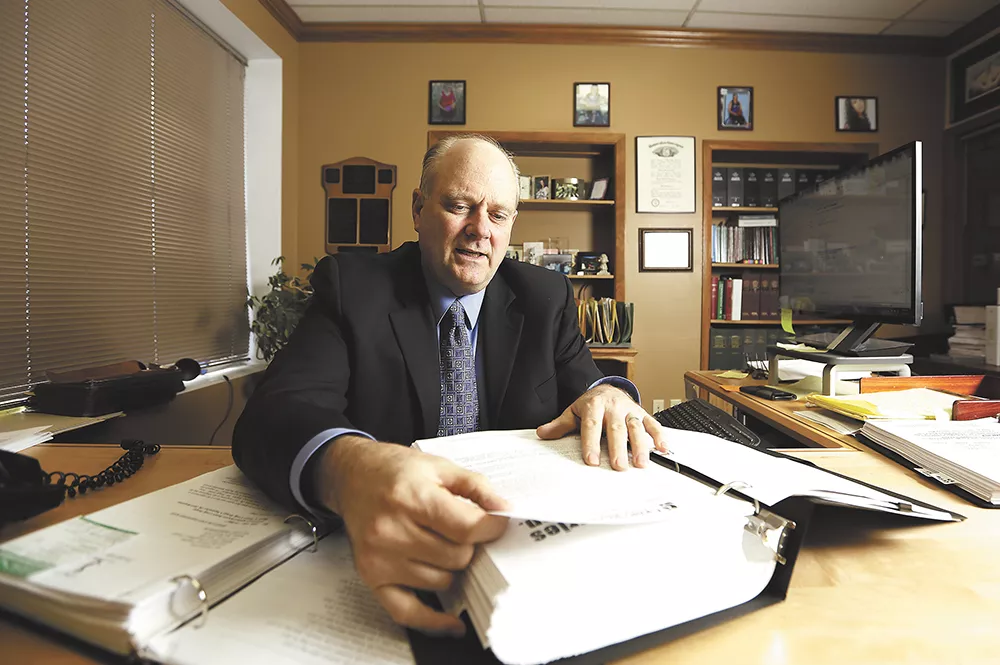

For more than a year, Jim Sweetser, the personal injury attorney Hendrix hired instead, has been locked in a battle with Swapp about the practice — even going as far as to file a grievance with the Washington State Bar Association. Swapp argues that he's providing accident victims with an important service. But many of Swapp's injury attorney colleagues consider the direct-mail tactic unseemly, unethical and possibly even a violation of federal law.

"This is chasing people who are injured for purposes of profit," says Sweetser, the former elected Spokane County prosecutor. "Everybody's heard lawyer jokes about ambulance chasers or sharks or greedy bastards or liars or manipulators."

This marketing tactic, Sweetser and other local attorneys say, plays right into the worst stereotype of the legal profession, and threatens to further tarnish its reputation.

"We all get tarred," he says. "We all get feathered."

But at the same time, Sweetser worries that directly targeting accident victims is so effective that firms like his will have to resort to it just to survive. In Washington state, the tactic has been on the rise. "This is not about Swapp," Sweetser says. "This is about where the legal profession is heading."

Soon, he warns, it won't just be one or two accident lawyers mailing victims like Hendrix after tragedies.

It will be dozens.

BETTER CALL SWAPP

In the dozen years since a marketing survey brought him to the city, Craig Swapp has spent millions of dollars making sure that Spokane knows the name Craig Swapp. "No Fee unless YOU WIN," proclaims a Swapp-branded billboard on Division Street, with the attorney grinning in his suit. "One Call That's All!"

A few miles down the road, a red billboard overlooks the northside Deaconess emergency room: "Car Accident? CraigSwapp.com."

Then there are TV, radio and internet ads.

None of those ads can target only people who've just been injured in a car accident. But tap into public records, and there's real power.

It's 8:44 am on March 11, and Marissa Ibarra has just ordered 15 accident records. Ibarra's a marketing specialist in Boise ordering Washington state accident records for Craig Swapp, who's based in Utah.

More than 11,000 auto accidents happen in Washington state every month. Every single time, officers fill out reports about the drivers and the crash, and every single time, that information gets uploaded to Washington State Patrol servers.

For the past four years, Washington State Patrol has made getting that report nearly as easy as downloading a movie from Amazon. All Ibarra has to do is open up WSP's Requests for Electronic Collision Records site, enter a date in the search field, and start clicking tiny shopping cart icons next to the list of names.

The only speed bump? You're capped at ordering 15 records at a time. So at 8:56 am, Ibarra orders another 15. Then another. Within 35 minutes, Ibarra has already purchased more than 60 Washington accident collision records for Swapp.

At $10.50 per report, she's run up a bill surpassing $600. Last January, Swapp spent more than $4,300 on these reports. For Swapp's firm, this information is worth the price.

"We wouldn't do it if it wasn't cost-effective to do so," says Swapp.

Over the phone, Swapp is soft-spoken and polite, using none of the fast talking or slick catchphrases you might associate with a trial attorney.

"I don't do anything I'm ashamed of," Swapp says. "I see it as legitimately a way to brand your firm."

He brushes off the idea that his mailers could be considered intrusive. He says he just sends one to each person — not exactly harassment.

"We all get junk mail — at least I do — and most of it goes in the garbage can," Swapp says. "That's where most of our letters go."

He doesn't see his targeted letters as ambulance chasing, but as a sort of service for the benefit of the community, full of tips that victims can use after an accident even if they never hire an attorney.

Indeed, those who receive Swapp's letters sometimes are grateful. Alex Hooper of Spokane Valley dodged a woman whose car was sliding into a snowy intersection last year, but ran his truck into an off-duty police officer's car. He raves about how helpful Swapp's mailers were. He was ready to call an attorney when Swapp's packet came in the mail.

"They had everything. They had the accident report. How the accident happened, the whole diagram," Hooper says. "Honestly, I actually thought it helped me out. I didn't have to spend half a day down at the courthouse to find that information."

For others, the tactic backfires.

In his small Browne's Addition apartment, 50-year-old Danny Kask unbuckles his medical boot to show off his foot, swollen and bruised after he was hit by a texting driver during Hoopfest weekend. Until he heals, he's stranded upstairs, relying on neighbors for groceries.

The package from Swapp arrived only a few days after the accident. It was the legal equivalent of the promotional packet that colleges send out to high school valedictorians.

Kask ripped open the large envelope, and found a sleek black-and-red folder with the Craig Swapp logo. Inside were business cards, color fliers and a glossy 24-page magazine, illustrated with photos of gavels, scales and bashed fenders and shots of Swapp with satisfied clients. He knew who Swapp was, but didn't appreciate the intrusion.

"I see him on TV all the time. 'One Call That's All''' — Kask sarcastically twirls his finger in the air — "and all that bullshit. Pardon my language. But I just didn't understand why I received that in my mail, when I didn't even contact him."

He'd already hired Jim Sweetser as his attorney. Kask found Sweetser the old-fashioned way — through an ad in the phone book.

Swapp is not the only attorney in Washington state using accident reports to gin up new business. Fuller & Fuller Law Firm, in Olympia, uses the same tactic. And on average, Fielding Law Group, with several offices in the state, buys more than 2,800 collision records monthly from Washington State Patrol.

One of those collision records revealed information about Everett aircraft mechanic Paul Schubert. He was on his motorcycle on the way to a union meeting when a car blew through a stop sign and collided with him, bashing his bike and breaking his bones.

The letter from Fielding Law Group, four days later, just irritated him.

"You're really in a delicate situation, physically, mentally, emotionally," Schubert says. "These people — you're just a number. I felt like they just want to take the case, retain me, settle out... I felt like a commodity being traded."

The whole notion of large-scale data mining made Schubert feel like he wasn't going to get adequate representation.

"They're getting names and numbers and incidents and fishing to see what they can get, and collect as many people as they can," Schubert says. "It's not different than dropping a net in the ocean and grabbing every fish, and throwing out the ones you don't want."

Attorneys throughout the region have decried the practice. The Washington State Association for Justice, an advocacy organization for trial lawyers, explicitly discourages it.

"I won't say it's unethical. But it gives the appearance of being unethical," says Spokane attorney Tim Nodland. "That smacks of trying to get cases at any cost. Money, money, money."

In Idaho, too, some attorneys react with disdain.

"I'm trying to think to myself," says Coeur d'Alene personal injury attorney Jim Bendell. "Is it technically unethical or is it just gross and disgusting?"

In one sense, this is an old debate. Three decades ago in Florida, when the state's attorneys were sending out 480,000 mailers to accident victims every year, the Florida Bar conducted a survey. Most of the accident victims considered it to be an invasion of privacy. Forty-five percent thought the tactic was "designed to take advantage of gullible or unstable people," and more than a quarter said it had harmed their view of the legal profession.

The Florida Bar quoted angry Floridians enraged by the gall of lawyers who were trying to take advantage of their grief, describing themselves as "appalled and angered" and the marketing scheme as "beyond comprehension" and "despicable and inexcusable."

In Swapp's case, he says he tries to avoid targeted mailers when victims have died. "We're trying to make a brand, not create enemies," he says. "But sometimes you don't know. They die two or three days after an accident."

Ultimately, the Florida Bar's conclusion left little room for nuance. Direct mail solicitation of victims immediately after tragedies, it argued, was conduct "universally regarded as deplorable and beneath common decency because of its intrusion upon the special vulnerability and private grief of victims or their families."

TURNING UP THE VOLUME

It's possible that attitudes toward privacy have changed since the Florida study. The entire business model of companies like Facebook and Google consists of selling your information to ad companies. Many of us eagerly hand over vast amounts of personal information in exchange for the right to like a friend's vacation photo or take a photograph of a Pokémon. Google "Craig Swapp," and you'll be followed online for days by targeted banner ads for Swapp's services.

But public records are different: Washington and Idaho residents don't have a choice whether their records are accessible, any more than they have a choice to be hit by a car. Now, thanks to the rise of the internet, getting collision records is faster than ever. Sites like BuyCrash.com let companies purchase reports from multiple states in bulk.

In a sense, Washington State Patrol's efforts to improve its collision report process has backfired and become a major burden for the agency. In 2011, WSP launched its sleek new Requests for Electronic Collision Records system, allowing requesters to sometimes get their hands on collision reports the day after the accident. Swapp says that he started targeting accident victims with direct mail about the same time, as he witnessed other firms doing it.

In the four years since, the volume of collision records being requested through Washington State Patrol has more than tripled, on track for more than 200,000 reports this year. Some of those requests are from accident victims or insurance companies. But more cars aren't getting in accidents. WSP collision records manager Patrick Gibbs blames the rise on people like Swapp.

There are seven employees working in the collisions records department of WSP, he says, and around a third of their time is entirely dedicated to redacting and fulfilling batch requests like those from Swapp. While the collision report fees generate as much as $115,000 monthly, that money goes to the state's motor vehicle fund, not to WSP. Others ask to inspect the records in person — 150 collision records at a time — and the state gets nothing.

Make no mistake, Gibbs is frustrated. When the Washington State Public Records Act was passed, he says, he doubts it was intended to be used to gin up business after car accidents.

"We spend so much time providing these records for that purpose," Gibbs says. "They're using it for their own personal gain or business gain. The law is being abused."

Meanwhile, the sheer volume of injury cases that Swapp takes on underpins a long-running cultural conflict between firms like his and traditional, old-school firms who litigate fewer cases and frown upon targeting accident victims with mail.

"Most good lawyers who have good reputations don't need to do this type of activity to get cases or clients," says Chris Davis, an attorney in Seattle.

Several local personal injury attorneys characterized high-volume firms as "mills" or "churn 'em and burn 'em" attorneys. They cite examples of clients they've had who have been given incorrect advice by inexperienced, overwhelmed attorneys.

"They need to settle cases quickly, so they will take shortcuts," Davis says.

Swapp dismisses this criticism as sour grapes.

"We represent and help a lot more people than they do," Swapp tells the Inlander. "That's our goal: To help as many people as we can."

There's no question that runaway success has its cost. A decade ago, Swapp was pouring nearly a half-million dollars in more traditional advertising into Spokane every year, and the firm was taking in so many cases that his Spokane office couldn't handle them all. And that was before Swapp was using targeted direct mail.

"It became successful overnight," says Erik Highberg, Swapp's sole Spokane attorney at the time. "The first couple years, it went from just a few cases to just overloaded."

Sweetser says he never handles more than 20 cases in active litigation at the same time. But by 2008, Highberg was juggling as many as 108. He says he'd put in 12-hour days and 80-hour weeks, working on holidays and weekends to try to catch up.

"We were at the high-water mark, and I was holding on to the fence as the water was rising," Highberg said in a deposition, describing the wait to bring on another attorney. "I was ready to get admitted to the cardiac unit any day."

He's compared the firm to an "assembly line."

Crucial tasks fell through the cracks. Swapp's firm failed to serve a complaint to two truckers who hit a woman in Oregon. As the statute of limitations for her lawsuit expired, the woman witnessed her case wither and die. The resulting malpractice case, accusing Swapp's firm of professional negligence and dishonesty, lasted years and resulted in a $3.5 million jury verdict, now under appeal.

In Swapp's deposition, he shifted part of the blame to Highberg for not being able to keep up, saying, "I think he was probably not as efficient as he could have been."

Today, Swapp says the firm has learned from the incident, and has altered how it assigns cases to its attorneys. There are six lawyers in Swapp's Spokane office, though Swapp won't say what their caseload is. That's "proprietary."

As evidence that most of his clients are satisfied, Swapp points to the fact that these days, his firm generates nearly half of its business from positive word-of-mouth referrals rather than from advertising.

Highberg now has his own firm. He says he doesn't believe in targeting accident victims using state records.

"I don't like the idea of somebody's family member getting hurt and then they get direct solicitation in the mail," Highberg says. "I don't believe it's appropriate."

STRAWS and BROKEN BACKS

As much as Swapp defends his advertising tactics, there are ways other businesses use accident records that make him uncomfortable. Like chiropractors.

"That's where a lot of abuses I've seen come from, in the past, nationwide." Swapp says. "We had a guy in Utah who would get police reports, and would call the accident victims and offer them a free visit. And put a hard sell on them. That's not appropriate in my mind."

In many ways, the businesses of personal injury lawyers and chiropractors are intertwined. Attorneys refer their clients to chiropractors, and chiropractors refer their clients to attorneys.

Chiropractors use direct mail too. ("Is pain from your car accident sucking the fun out of your life??" read a letter from Federal Way chiropractor Jay Baker that literally included a straw.)

Yet the rules governing chiropractors are a lot looser. Lawyers are barred from calling potential clients directly. Chiropractors have no such limitation. Chiropractors can call anyone not on the Do Not Call List.

A lot of time, a chiropractic office doesn't do the work directly. Sometimes they go through a third party.

Week after week, records show, JustUs Advertising, a Vancouver company, had inspected westside collision records at Washington State Patrol's offices, 150 at a time. When contacted by the Inlander, John Prepula, owner of JustUs, declined to elaborate on exactly how the records were used.

But the JustUs website brags at great length about how it uses car accident lists to send recent car accident victims postcards and phone calls advertising chiropractic practices.

At first glance, one sample postcard to send to victims sold on the JustUs online store appears to be a message from a creditor.

"FINAL NOTICE: RESPONSE REQUIRED REGARDING YOUR AUTO ACCIDENT" the card reads, offering a free massage and auto accident evaluation. "IMMEDIATE action required."

If that sort of mailer was coming from an attorney, Swapp says, that would not be appropriate.

And where Swapp says he only sends one letter after an accident, the JustUs blog recommends sending three, with messages "tailored to the expected cycle after an accident," and then combining that with telemarketing.

On a page illustrated by a "Shhh... Top Secret!" graphic and a picture of a briefcase full of stacks of $100 bills, the site explains that JustUs will call recent auto-accident victims, but promises to keep the identity of the clinic behind the call secret.

"In order to avoid any negative reviews or impressions that can come from telemarketing, we never reveal your practice name until someone in an accident requests a referral," it reads.

But Prepula also has a place where he draws the line. Sometimes, he says, he gets calls about third-party groups who will tell accident victims that they're calling on behalf of the victim's insurance company, to set up a chiropractic evaluation.

"Which to me is totally deceptive," Prepula says, claiming they don't do that.

Lawyers across the state have echoed this concern, calling the practices of some third-party groups selling on behalf of chiropractors deceptive and predatory.

Shirley Bluhm, a personal injury attorney in Olympia, says a client of hers received direct mail from two different attorneys after her accident, and a phone call from a third-party group called Accident Angels.

"Accident Angels gave her this spiel that if she's injured, then they can help her find somebody to get treatment," Bluhm says. "They were going to send her to a free consultation to this chiropractor. She said 'great.'"

But she says her client later learned that her limited personal injury protection insurance had been billed for her chiropractic visit. It wasn't free after all.

"It was shocking to her," Bluhm says. "She was just taken aback."

More recently, Bluhm conducted her own investigation of the group. She called Accident Angels on a number she got from one her clients, pretending to be an injured accident victim. She feigned ignorance, asking the voice on the other line questions about insurance.

"What he provided was not accurate information," Bluhm says. Accident Angels did not return a call seeking comment.

Chiropractors, at least, are considering policy changes. The state Chiropractic Quality Assurance Commission has received multiple complaints about certain advertising practices and is considering reworking the rules for contacting potential clients. But so far, lawyers like Sweetser hoping for the same efforts from the Washington State Bar Association are out of luck.

exhausting OPTIONS

Early last year, Sweetser says, he and the staff at his law firm held a meeting. They wanted to consider, seriously, whether to start targeting collision victims with direct mail.

"Do we have to compete this way?" he asked. They decided against it, feeling it was unethical and of dubious legality.

So since February of 2015, Sweetser says he's been trying to get a clear answer on whether the direct mail practice is currently legal — asking the Washington State Bar Association, Washington State Patrol and the state Attorney General's office.

All three, however, indicated to the Inlander that they consider the use of collision reports to target accident victims to be legal.

"We could choose to stop it at any time," Swapp says. "If the Bar has determined there is something wrong with it, we would stop."

Oddly, each collision request form explains that state law "prohibits the use of lists of individuals provided by the Washington State Patrol for commercial purposes." But WSP says that doesn't actually stop the collision records from being used for commercial purposes. They're considered batches of individual records with names, but not technically a list.

This sort of parsing exasperates Sweetser.

"There you go," Sweetser says. "Loophole. Loophole."

His best hope is a class action lawsuit from Chicago, which alleges that since collision reports often contain information obtained from driver's licenses, when lawyers use them to contact accident victims, they are violating the federal Driver's Privacy Protection Act.

The ironic thing is that in Utah, where Swapp is headquartered, he can't do what he does in Washington and Idaho. State law there doesn't allow Utah accident records to be released to attorneys — or chiropractors — fishing for clients.

The Florida Bar found another way to fight the direct-mail epidemic: They mandated that their attorneys had to wait 30 days after an accident to contact victims and offer their services. Some fought like hell to stop it, challenging it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

But while the court had previously ruled that attorney advertising was protected by the First Amendment, it upheld Florida's moratorium. The Washington State Bar Association hasn't followed suit.

Last Monday, Sweetser received a mass spam email from a lawyer marketing guru explaining that, however Sweetser feels about direct mail, he should know that other lawyers are using it to "poach clients from right under [his] nose, unceremoniously and unchallenged."

This is his fear. He says he's about ready to retire, but as younger lawyers, including his son, take over his firm, it may be forced to adopt Swapp's tactics.

"There's going to be more and more attorneys doing it. Out of survival. To compete," he says. "Maybe ambulance chasing is the new reality." ♦