Christine Quintasket came into this world, and left it, in her self-imposed role as a diplomat.

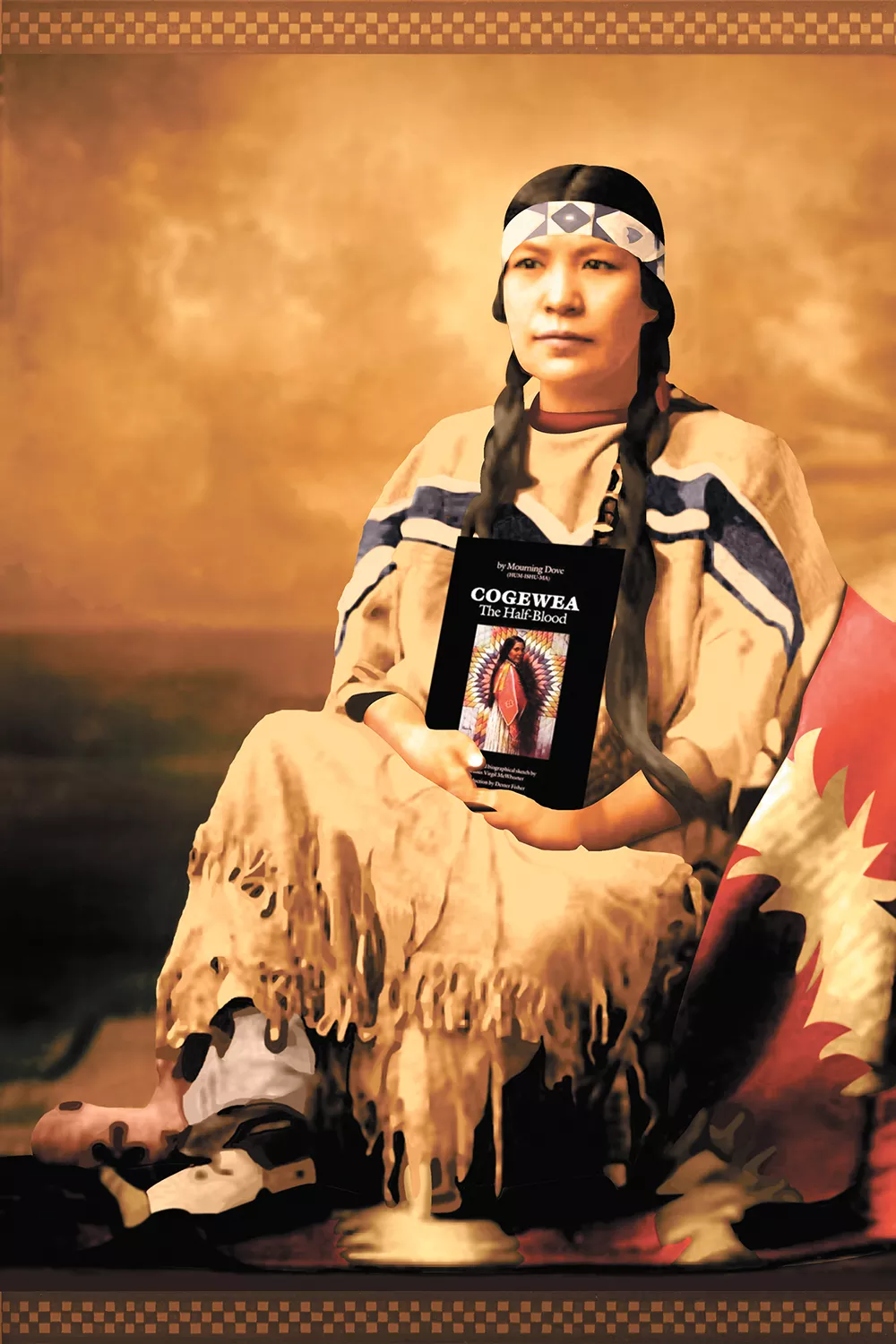

The Colville woman, who published two books under the pen name "Mourning Dove," was born in a canoe crossing the Kootenai River from North Idaho into Washington in 1888, according to family lore.

"I really like the symbolism that she was navigating the plateau right from the moment she was born," says Laurie Arnold, director of Native American Studies at Gonzaga University, who recently published an article on the Colville woman's influence.

For much of her life, Quintasket traveled throughout the Columbia Plateau, collecting stories of Colville and Okanogan people that she would eventually compile into a book. As the first Native American woman to publish a novel, Quintasket felt it was her role to preserve Native culture for younger generations, as well as inform those (typically white people) unfamiliar with it.

As a bridge between two cultures, the story goes, Quintasket's life came to an end in 1936. She was staying with a non-Indian couple, who repeatedly asked her to show them her "spirit power" — a private part of one's personality that is to be honored and protected.

Finally, Arnold says, Quintasket relented, in part because of her desire to facilitate understanding of tribal culture. Soon after, she became ill and never recovered. In 1988, a Colville elder said that her choice cost Quintasket her life.

But perhaps more significant for Arnold, who is an enrolled member of the Sinixt Band of the Colville Confederated Tribes, are the details in between, and how they've been interpreted by her peers.

"Scholars for a long time were hung up on this notion about [Quintasket] that framed her as suffering because of her biculturality," Arnold says. "But that characterization is such an oversimplification."

In her article published recently in Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Arnold aims to give a more complete picture of Quintasket as an activist and a public intellectual.

"She was doing work at the time that not many people were doing — men or women," Arnold says.

Although she probably didn't realize it at the time, this project started for Arnold when she was in high school, reading Quintasket's biography. But it wasn't until she returned to the text, after accepting her current position at GU, that she realized its flaws.

"As I was reading it, I was getting more and more frustrated with the characterization of her," Arnold says. "When you read the primary documents, it's quite evident that she is intentionally creating cultural continuity."

Those documents include letters from Quintasket to a man named Lucullus McWhorter, a white cattle rancher and historian who acted as an editor for Quinstasket's books.

Throughout their correspondence (publicly available at the Washington State University archives), Quintasket recounts her day-to-day activities and the two discuss edits to her manuscripts.

"I am going to the mountains again in August," she writes in the spring of 1930. "When flowers of mystery are in full bloom, and then I shall 'do my stuff.' Our book is going to be a success. [My] Indian beliefs will prove it."

Arnold uses this quote to show Quintasket's zest for her role as cultural advocate and ethnographer — a role she fulfilled through more than just her storytelling.

Quintasket acted as a liaison between the U.S. government and the Colville people for the Indian Reorganization Act (also known as the Howard-Wheeler Act), which she advocated for. The new law would give tribes more voice in their government, she argued.

"The reason I have fought for my people is this: I owe it to them, old men and women of the Colville Indians," she said at the Howard-Wheeler conference, which she attended as a delegate. "Let us hope that this new form of government will not be imposing on our old people, that you younger men and women will have a voice in the government of the U.S. Let us try a new deal."

The Colvilles ultimately rejected the law — a vote which remains a point of contention among members.

Quintasket was also instrumental in creating the first "dictionary" for her first language — Salish. She did this as she worked on her second novel, Coyote Stories, to help McWhorter, her editor, understand the text. No known copies of the dictionary exist today, Arnold says.

Quintasket also served on the Colville Tribal Council (the predecessor to today's Colville Business Council), and founded the Colville Indian Association.

In addition to all of this, she constantly traveled throughout the Northwest, collecting stories, and getting work where and when she could as a farmhand and housekeeper for non-Native folks.

"After working for ten hours in the blazing sun and cooking my meals, I know I shall not have the time to look over very much ..." she wrote to McWhorter one summer while revising Coyote Stories. "But fire them on, and between sand, grease, campfire and real apple dirt, I hope I can do the work."

Quintasket's life story carries some personal significance for Arnold, who strives to fill a similar role.

"I view this article, and others that I'll do on her and other leaders, as creating a consciousness of the Native peoples of the Columbia Plateau, because there really isn't one," Arnold says. "Not among scholars, and not among people who live here."

Arnold is working on a book about four influential Native leaders: Lucy Covington, Paschal Sherman, Joe Garry and, of course, Quintasket.

"It's about finding ways to tell plateau stories, and illustrate the dynamism of those lives without marooning them in the past," she says. "Which is so often what U.S. history does to Native peoples." ♦