It was November of 1800 when North West Company fur agent David Thompson first heard about some potential trading partners west of the Continental Divide. While visiting a Pikani Blackfeet winter camp on the upper Bow River, just south of modern Calgary, Alberta, a headman there expressed Blackfeet concerns that the white men would supply arms to Kootenai and "Flat Head" people. When Thompson declared his intention to investigate the Rocky Mountains anyway, the headman "warned us in a friendly manner to beware of the Flat Heads, who were constantly hovering about there to steal horses or to dispatch any small weak party they might chance to fall in with."

Those fears sound confusing to Americans schooled on the notion that it was the Blackfeet who terrorized the Rockies, stealing horses and intimidating outsiders. But Thompson had known Pikani leaders for more than a decade and understood some things about tribal interactions. His company represented British political power, and he needed to meet other powerful players to serve as partners in the beaver hide trade and to guide him on his intended journey down the Columbia River to the Pacific.

It is not clear exactly where that Pikani Blackfeet headman (or his translator) came up with the term "Flathead," and several years passed before Thompson began to assemble the puzzle of names, bands, families, and territories on the west side of the Rockies. In spring 1807, he and a small party of voyageurs and their families crossed the mountains to establish a trade house at the Columbia River's source lakes in what is now southeastern British Columbia. Intended primarily for trade with the Kootenai people, this Kootanae House attracted visitors from across the region. Before long the term "Ear Pendant Indians" — Thompson's English translation of people his French-Canadian voyageurs called Pend Oreille — began to appear in his daybook.

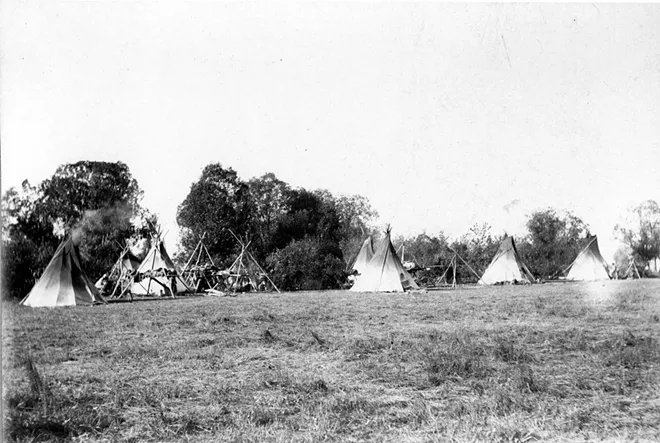

Thompson's understanding expanded after he arrived at what we now call Lake Pend Oreille in the fall of 1809. Guided to a fall gathering of area tribes near the modern town of Hope, Idaho, Thompson oversaw the construction of a post that he named Kullyspel House after the people whose home territory he had entered. Before winter set in, he traveled downstream to another encampment at Cusick, Washington, to meet key Kalispel elders.

Several of these elders and their families kept winter camps upstream in what is now northwestern Montana. Following their lead, Thompson had his crew construct a second post that he named Saleesh House near modern Thompson Falls. This Saleesh House served as the trader's base of operations over the winters of 1809-10. In the spring of 1810, he dispatched scout Jaco Finlay to construct Spokane House to complete his circle of trade among Salish-speaking people. After canoeing to the Pacific, Thompson returned to Saleesh House over the winter of 1811-12 and followed guides east as far as Missoula and north to Flathead Lake.

THE LANGUAGE

Thompson, who grew up speaking Welsh Gaelic, understood that language would play a key role in the success of his business venture. He had learned English at school in London, then Cree as a teenaged apprentice on Hudson Bay. He picked up a version of French from mixed-blood North West Company voyageurs and smatterings of Iroquois from expert canoe paddlers who accompanied him on all his journeys. After Kootenai people introduced Thompson to the Salish bands who lived both upstream and downstream from Lake Pend Oreille, the trader soon realized that closely related dialects of Salish language stretched from today's Flathead Lake west all the way to the Columbia and south into the Spokane and Coeur d'Alene Country.

Thompson tried to make sense of all this by writing down a word list in his journal. Many early white visitors, including Lewis and Clark, made similar lists as they attempted to figure out how to do business as they met new tribes within the kaleidoscope of language and cultures in western North America. Thompson's original attempt included 80 Salish terms, with most of them focused on daily needs such as food, trade goods, and weather. He used spaces and underlines in attempts to capture Salish sounds and inflections not present in English; in this effort he was surely aided by similar qualities in his native Welsh.

Over the winter of 1809-10 at Saleesh House, Thompson had more time to devote to his passion for language. On a clean page of the same notebook that contained that first short list, he wrote down the heading Sa leesh & Kullyspel Vocabulary 1810. In left-hand columns on succeeding pages he neatly inscribed almost one thousand English words from A to Z. These English words plumbed Thompson's state of mind during his time in Salish country, far beyond any territory yet secured by American or British power. On the "A" list alone he asked for equivalents to "abandonment," "abusive," "absent," "I am afraid," "affront," "aground," "ancient," and "astray," as well as questions about aunties, abilities, and aurora borealis. The Salish column remained blank for all of these.

The only person named in Thompson's vocabulary was a Kalispel headman identified as "Cartier." Fur company voyageurs loved to bestow nicknames according to appearance and actions, and this one could relate to the well-known New World explorer Jacques Cartier. Thompson rendered Cartier's name in the Salish column as "Chin a la mal lé," a name that also appeared several times in his daily journal. Although no connection to any Salish-speaking individual or family has ever been established for Chen a la mal lé, linguists assume that he is the man responsible for most of the four hundred or so Salish words that Thompson did enter into his vocabulary.

As the list developed, Thompson began to ask for phrases and sentences that would help him navigate his new surroundings: "Has he seen it?" "When will you return?" "Where is my horse?" Other speakers occasionally joined the process, so that new words stretched across the page to the right: a Kootenai word for "snow;" fragments that seem to derive from Spokane or Okanogan dialects; logical answers to his original questions such as "Do you want us to know?"

"I can see how the new people were curious of our ways, our traditions, but since it was too hard to find out, their curiosity probably went by the wayside."

Modern Salish linguist Steve Egesdal has noted that Thompson's ear was sharp enough to capture renderings of Salish words that remain comprehensible today to both modern tribal speakers and academic linguists.

The many blank spaces also revealed inevitable confusion and misunderstanding as Thompson attempted to delve deeper into the Salish culture. During the two winters he spent at Saleesh House, he had time to sit with elders and try to converse with them about their views on natural history, human nature, ecology, death, and spirituality. The fur agent remained a doggedly curious man but admitted that his surface grasp of the language prevented him from gaining any deep insight into their beliefs.

Kalispel Language Program Director JR Bluff has a response to Thompson's experience. "I can see how the new people were curious of our ways, our traditions, but since it was too hard to find out, their curiosity probably went by the wayside," he says. "People always seem to want the quick answers, but not too sure they would want to truly understand our ways."

THE RIVER

Thompson retired to eastern Canada in 1812 and took up serious cartography. In his landmark "Map of North America from 84º West," he combined his own surveying expertise with information from his Salish mentors to present the first accurate European-style map of Salish territory. The "bold sheet of water" that we today call Flathead Lake appears as Saleesh Lake; the river that flows south from its outlet, marked on modern maps as the Flathead River, is the Saleesh River because for him it defined the home territory of Salish-speaking people.

MODERN KALISPEL SALISH GUIDE

BEAVERsqlew̓ (skul lou)

STURGEON

sc̓mtus (sim e toose)

SWAN

spqmi (spuk a mé)

WOOD

luk̓ʷ (look oo)

YOUNGER SISTER

łccʔups (ilth cher oops)

CAMAS

ítxweʔ (eet too woy)

Today the Flathead cedes its name to the Clark Fork at the rivers' confluence near Paradise, Montana; to the elders Thompson spoke with, it remained the Saleesh River from there to the ear-shaped lake where he met Kalispel people. Thompson marked this as Kullyspel Lake.

Today we call the river that runs out of Lake Pend Oreille and travels west and north to curl around the 49th parallel and meet the great Columbia the Pend Oreille River. But on Thompson's map it remained the Saleesh River because it contains the same waters draining off the west slope of the Rocky Mountains and because the same Saleesh people lived and flowed along its length, comfortable in their relationship with the entire drainage for untold generations. Although Thompson never visited Priest Lake, tribal information allowed him to place it unnamed in its exact location. The breadth of his Priest Lake is greater than it looks on a modern map but otherwise the shape looks remarkably accurate, including Kalispel Bay and the separation between the lower and upper lakes.

The assembled sheets of Thompson's great map measured ten feet wide by six feet tall and displayed all the major watercourses between Hudson Bay and the Pacific from the latitude of central Oregon to Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories. Even so, he managed to include salient geographical details that illuminate the lives of people through language. He marked modern Camas Prairie, Montana, as eet too woy plains, a fair approximation of the Salish word — ítxweʔ — for one of their key cultural plants. He applied the same designation to similar abundant root grounds surrounding the Kalispel encampment at the mouth of Calispel Creek, directly across the river from the powwow grounds on today's Kalispel Reservation. Each May the wet meadows there still bloom blue with this same camas.

"Camas is a strong symbol of our people. It represents not just a flower, not just a trade item, but something more that was in us all."

Eet too woy represents a single word that one white visitor managed to absorb, and barely hints at the richness of a language that includes a host of other terms for camas — the flowering plants, the dark-skinned tubers, the community harvest, the recipes for baking those roots in an earth oven. But it does show that Thompson recognized a vibrant ongoing culture through their spoken Salish language.

Two centuries have passed between the moment that Thompson accepted gifts of roasted camas and dried salmon from Kalispel elders at the Cusick encampment. The language spoken at that meeting still describes an intimate connection between people and landscape over a much greater swath of time.

"Camas is a strong symbol of our people," emphasizes JR Bluff. "It represents not just a flower, not just a trade item, but something more that was in us all."

"It is a gift of nourishment, survival. We were taught how to dig it, prepare it, store it, respect it. Our lives followed these basic steps for generations," Bluff says. "The entire village knew this and carried out their responsibilities during the camas season. All of this was around one word, one food, one camp. Very easy to just memorize one word and label it as 'a food that was traded.'"

Thompson understood that his fur trade posts would bring great changes to the tribes that engaged in business with him, and that language would provide the key to his success. What he might not have fully grasped was the deep power of that language and how it related to the resilience of Salish culture. ♦

Jack Nisbet is the author of several books and collections of essays that explore the human and natural history of the Northwest, including Sources of the River and The Mapmaker's Eye, two award-winning biographies of cartographer David Thompson.