On Sept. 8, Queen Elizabeth II died at her Scottish home of Balmoral. While her death at the ripe old age of 96 did not come as a surprise, it was, nonetheless, a global phenomenon. To some, the queen's death marked the end of the era. Born in 1926, Elizabeth was the United Kingdom's longest reigning monarch, serving 70 years on the throne. To her mourners, she was a constant in a changing world.

To her detractors, however, the queen represented the shameful legacy of British colonialism. Elizabeth II ascended the throne during the waning days of the British Empire, with British forces engaged in the violent repression of independence movements from Malaya to Kenya.

Though conflicted about her legacy, people around the world were transfixed by the global media coverage of the queen's death, Americans not least among them.

The American obsession with the British royal family is perplexing. The United States was born of the rejection of the British monarchy, yet the success of the Netflix series The Crown and the content of morning TV shows and grocery store tabloids pay testament to the American love of celebrity.

Two hundred years ago, Americans greeted news of the death of George III with the same voracious appetite for royal gossip. George, Britain's longest reigning king, died at Windsor Castle on Jan. 29, 1820, at the age of 81, after 60 years on the throne. He had been the king that Americans had loved to hate, a bloodthirsty tyrant who embodied the brutality of British colonialism. The Declaration of Independence documented his many crimes: "he has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people." Yet, when news reached the United States of George's death, Americans couldn't get enough of it.

It took about five weeks for the first reports of George III's death to reach the Atlantic port cities. As was common practice among American newspapers in the early 19th century, The Mercantile Advertiser of New York reprinted the official announcement of his passing from The London Gazette on March 11. The news soon spread along the Eastern Seaboard, arriving in Boston on March 13 and Charleston, South Carolina, on March 14.

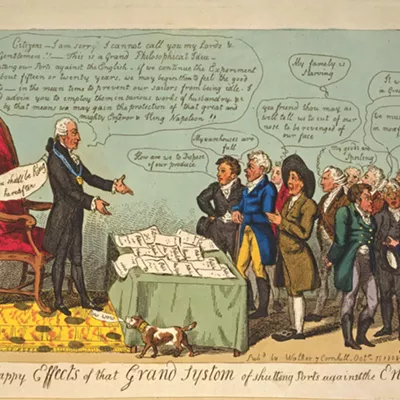

What Americans wanted most was some juicy gossip. The new King George IV and Queen Caroline were the Charles and Diana of their day. Forced to marry Caroline by his father, who hoped that marriage would help to curb his son's appetite for fast living, the future George IV soon despised his wife, and she him. The couple separated after barely a year, and Caroline became a figure of public sympathy for her mistreatment at the hands of her philandering husband.

The stormy relationship of the new king and queen titillated American readers in much the same way that tabloids revel in the Windsor family drama today. The Alexandria Herald of Virginia speculated about Caroline's coronation. George IV's supporters in Parliament had failed to pass a bill in time to prevent her becoming queen on the death of his father. Would she now be crowned? The notorious Henry VIII had refused the coronation of his queen for two years! What would the king do next? Readers wanted to know.

It is tempting to dismiss the American obsession with celebrity as a recent development, a sign of our fall from grace.

Americans could watch live coverage of Elizabeth II's funeral in 2022, taking in the sights and sounds of the solemn pageantry. Such technology was beyond the wildest dreams of people living in 1820. Yet, American readers were transfixed by the smallest details of George III's funeral on Feb. 16. The Salem Gazette of Massachusetts reported the mood from London. The city's businesses were all closed on the day of the funeral, and the "solemn tolling of the bells of every church" had "a most gloomy and melancholy effect." The Boston Intelligencer provided a colorful commentary on ceremonial minutiae, including a detailed description of the king's coffin, from its silver handles to the specific "tint" of its blue velvet cover. No detail was too small for the American public.

It is tempting to dismiss the American obsession with celebrity as a recent development, a sign of our fall from grace. We always imagine that our forebearers were far more seriously minded than we are. But comparing the way that Americans greeted the news of the death of their former colonial overlord in 1820 with the reception that Elizabeth II's death received in 2022 shows that we have more in common with the founding generation than we might realize. After all, who doesn't enjoy some tasty gossip now and then? ♦

Lawrence B.A. Hatter is an award-winning author and associate professor of early American history at Washington State University. These views are his own and do not reflect those of WSU.