The blinds on the living room’s sole window are closed, so Bhim Dhakal points through the open door to the field outside where he last saw his son.

It was near 11:30 on the night of June 11, and Krishna Dhakal, 17, was out there with two friends from out of town, Krishna Dhital, 21, and Dilliram Bhattarai, 28, both of Tukwila, Wash., and both Bhutanese refugees like Dhakal.

At some point that night, the younger Dhakal and his friends got in Bhattarai’s black Acura and left.

“They were talking outside,” Bhim, 44, says through a translator, as he sits on his couch with family members. “They said they’d come back, but they never did.”

It’s been almost three weeks, and there is still no sign of the three men.

Washington is home to more than 1,000 Bhutanese refugees, about 300 of whom are in Spokane. Bhutanese refugees started coming to the Inland Northwest about three years ago and faced several hurdles: learning English, finding employment and adjusting to a new life after years living in refugee camps.

But this episode, Bhutanese leaders and refugee activists say, has shaken the tight-knit community.

Theories abound as to what happened to the three men after they vanished from the East Mission Avenue apartment complex.

Maybe they’re lost somewhere in Spokane, Bhim Dhakal says, or were kidnapped. After they failed to return home the next morning, Bhim says he walked around the nearby riverbanks looking for his son. He thought whoever was driving the car was careless and maybe ended up in the river.

But his son still did not turn up, and Bhim had to go to his job picking cherries at an orchard in Brewster. The following Monday, Krishna’s mother went with an elder at Faith Bible Church who has worked with the Bhutanese community. He helped her make a missing person’s report to the Spokane Police Department.

The case is “kind of a mystery,” says Chet Gilmore, a Spokane Police detective assigned to the case. After receiving the report, Gilmore says he personally checked the riverbank near Dhakal’s residence both on foot and with a helicopter. Authorities at both the Canadian and Idaho borders have no records of the Acura crossing, and a notice has been sent to law enforcement nationwide that the car is missing, Gilmore says. There has no been bank activity for the two older men, and Krishna has no bank account.

As to whether a crime has been committed, Gilmore says he isn’t sure either way. So far, Gilmore says he has no leads to follow and no idea of the men’s whereabouts. Gilmore adds that he has not found any indication the men have criminal records.

“I think that something tragic has happened,” says Mark Kadel, director of World Relief Spokane, which is one of 10 organizations nationwide that contract with the U.S. Department of State to help new refugees find housing, get jobs and obtain language skills. He suspects they may have gotten lost, though is suspicious as to why the car has not yet been found.

“Everyone is

looking for the boys. Children don’t just run away,” says Kadel, who has

been working with Spokane’s Bhutanese community since the first family

arrived in the city in February 2008.

Up until his disappearance, Krishna Dhakal’s story was not uncommon among the Bhutanese living in America. After years in a Nepal refugee camp, his family left the country and was relocated to Spokane in September 2009, living in a complex almost exclusively tenanted by fellow Bhutanese.

The flight of the Bhutanese to the United States is the result of ethnic and religious differences within the mountainous country between India and China, says Lipi Turner-Rahman, a history instructor at Washington State University.

After inviting workers from nearby Nepal into Bhutan in the late 1800s to help with agriculture projects, the government began passing strict immigration laws. These laws, passed after World War II, were intended to force the Nepalese descendants to prove their Bhutanese citizenship through tax documents and other sorts of official papers. Tensions had also risen between the Nepalese descendants in the south — who primarily spoke Nepali and were Hindu — and the Buddhist rulers in the country’s north.

“For the government, being Bhutanese meant preserving Bhutanese culture — Bhutanese culture being a specific language, dress and culture,” Turner-Rahman says. The Nepalese descendants often did not conform to these ideals.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, many Nepalese descendents in Bhutan fled to camps set up by the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees in eastern Nepal after being forced out by Bhutanese authorities, who alleged that the Nepalese descendents were there illegally.

The United States began accepting Bhutanese refugees in February of 2008, Kadel says, and the first family to arrive in the country settled in Spokane. The Bhutanese refugee population in the U.S. now numbers around 40,000, Kadel says, while 73,300 displaced Bhutanese remain in camps in Nepal, according to the UNHCR.

“Many of the young people have been born and raised in camps,” Kadel says of the Bhutanese immigrants. “These are our new Americans.”

They aren’t alone. In this fiscal year, Burmese have made up the largest number of immigrants into Spokane, according to information distributed by the state’s Department of Social and Health Service’s Office of Refugee and Immigrant Assistance, with Bhutanese and Iraqis taking second and third place, respectively.

“This community is not very diverse, but welcoming of diversity,” Kadel says of Spokane. Unlike other cities, Spokane has few neighborhoods dominated by a particular group of immigrants. This, Kadel says, makes it easier for new immigrants to settle in, and Spokane’s refugee community now numbers over 20,000.

But many immigrants have struggled upon arrival due to difficulty finding work and learning English.

“They

work where they can find it,” says Brent Hendricks, founder of Global

Neighborhood, a Spokane-based organization that helps refugees with job

training and accessing social services. “Until you’re fairly fluent in

English, it's hard to get into even community college.”

Now, fear weighs on the minds of the community. At a Nepali-language service hosted at Faith Bible Church on Sunday, congregants told of how since the disappearance, they see Spokane as unsafe. And they’re praying for the return of Krishna and the others, who they regard as their adopted sons.

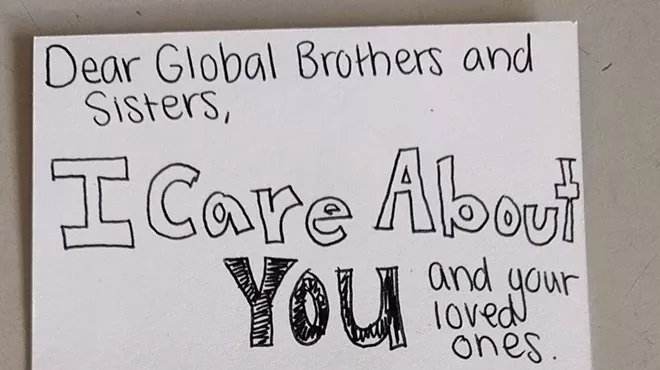

“We’re praying and we’re writing messages to friends,” says Bemal Rai, a former schoolteacher in a refugee camp in Nepal, where he lived for 18 years. Rai now gives sermons from the Bible to the Bhutanese, who come to the church on Sunday in a pair of yellow school buses.

“We’re talking to people in different states,” Rai says of their efforts to locate the missing men. “You can’t do any more than that.”

For Bijay Mongar, Dhakal was a friend, neighbor and fellow church member. He remembers playing soccer with him at Mission Park. Dhakal played goalie, he played forward. He lives above Krishna’s family at the complex on Mission Avenue, and goes to school with him at Lewis and Clark High School, where Krishna is to enter his junior year. The stress of losing his friend has taken its toll on the 16-year-old.

“It’s been going bad,” he says. “I missed finals because he was my friend and I’m sad too, because they’re lost.”

Loss is also on the mind of Bhim Dhakal, Krishna’s father. His son’s disappearance is hurting him, he says, though he thinks his son is still somewhere in Spokane. When asked whether he believed he would see his son again, Bhim was uncertain.

“It’s hard to say.”

Call Crime Check at 509-456-2233.