Earlier this month, Washington voters approved a mandate on smaller class sizes by a tiny margin. When an initiative campaign like this one gathers sufficient interest to reach the ballot, it's safe to say that the public is both interested in the policy and dissatisfied with current representatives' ability to address the issue adequately. And if you aren't dissatisfied with our education system, then it's likely you are not involved with it as a parent, student or teacher and simple ignorance is to blame.

Opponents of the class size reduction initiative expressed concern over spending, but redistribution of the more than $11,000 per student per year should be a feasible option. While I don't think this measure will solve our sprawling education crisis, at least it will prioritize teachers working directly with students. Small classes are one key component of the puzzle. The most engaging class in my school experience had less than 15 students. The small teacher-to-student ratio certainly played a part in my enrichment, but other factors were equally as important.

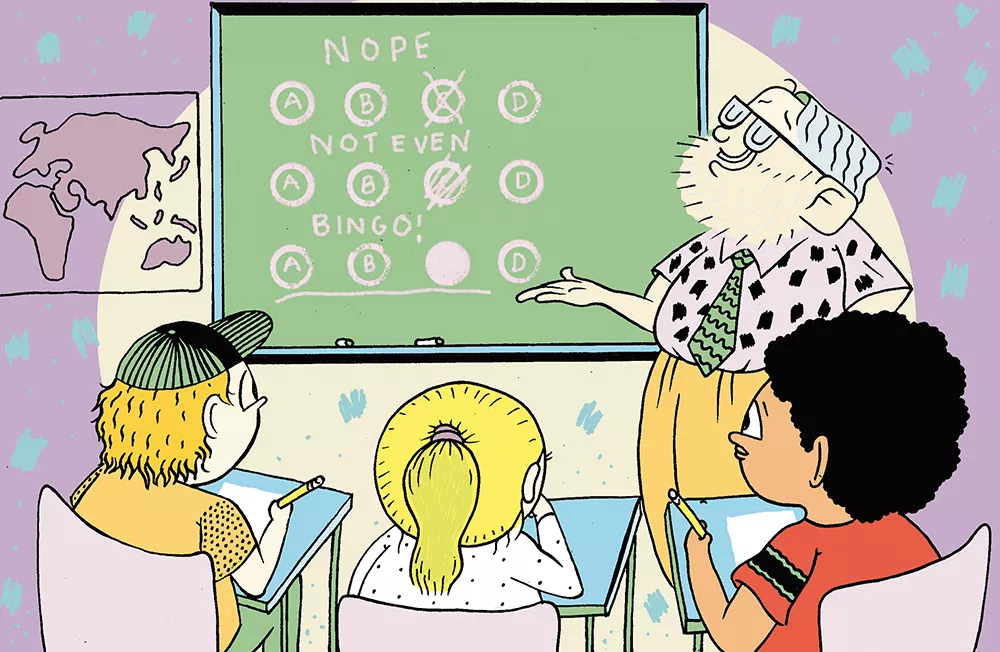

The culture of high stakes testing and the drive to measure everything have stifled the creative, messy and inquisitive process that constitutes actual learning. The small class I referenced above was a Social Studies option my senior year at Lewis and Clark High School called P.I.C.I. (Practicum in Community Involvement); it exemplifies the process-oriented learning that builds critical thinking skills and confidence. It probably did not directly help me pass the WASL, my generation's required standardized test, but six years down the road I am grateful that a few aspects of my education were free from the interference of testing and the culture it breeds.

Each student in P.I.C.I. chooses a community organization and a corresponding research topic to engage with for the entire year, culminating in a rigorously researched paper and presentation that fellow students have critiqued and improved along the way. Some students have had their research published. For others like me, their experience in this class helped spark a lasting interest in topics outside the outcomes-obsessed curriculum.

In my class alone, students grappled with topics like addiction and recovery, the working poor, the science of GMOs and the effects of corporate power on democracy. We argued, we researched, we wrote, and we learned about theories of social change. I worry for programs like this as schools are forced to "race to the top" and standards warp further from proven methodology toward outcomes that are easier to measure. My worry deepens when I see moves in Texas and Colorado to ensure that Social Studies curricula promote "pro-American" narratives over critical analysis of history and the forces that shape our society.

Education can and ought to change our lives. We often can't measure or predict how that will happen, and maybe that's OK. In the 2012 McCleary decision by the Washington Supreme Court, the justices ruled that the state must reform the education system and noted, "Pouring more money into an outmoded system will not succeed." They left the responsibility up to the legislature to create those reforms, but the real experts we need are students, educators and parents. We need to revolutionize the way we educate young people and we already have so many of the tools we need. Let's make it happen. ♦

Taylor Weech, who hosts the weekly public affairs program Praxis on KYRS-FM, is a Spokane writer and activist. She shares writing, photography and her podcast at truthscout.net.