Republican opponents of President Joe Biden have targeted his age as a weakness in his re-election bid. Biden will be 82 if he is sworn in as president in January 2025, and 86 at the end of his second term. Yet, the GOP's own likely nominee, Donald Trump, is only three-and-a-half years younger than Biden.

The Constitution does not disqualify someone from becoming president because of their advanced age in the same way that it stipulates a minimum age of 35. For some voters, the criticism of Biden and Trump is ageism, a form of discrimination that dismisses the value of the life experiences that senior citizens can bring to government. Nevertheless, there is no question that the likely 2024 presidential matchup will feature two of the oldest candidates in American history, with a combined age of 159 in November 2024.

Whoever emerges victorious in 2024, they will be at least a decade older than the current leaders of other industrialized democracies. Among the G7 nations (excluding Biden), political leaders vary in age from UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak (43) to Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida (66). Leadership in the G7 is multigenerational, including millennials, Generation X and baby boomers, like Biden and Trump. Some voters critical of Biden and Trump are less concerned about their mental and physical acuity than the stranglehold that the postwar baby-boom generation has had on the White House since Bill Clinton's election in 1992.

While the Founders did not include an age disqualification for holding executive office, Thomas Jefferson did write about generational change in American politics. Jefferson missed the debates surrounding the drafting and ratification of the new Constitution back home while he served as the U.S. ambassador to France. This didn't stop him from regularly corresponding with key constitutional players, including his protégé James Madison.

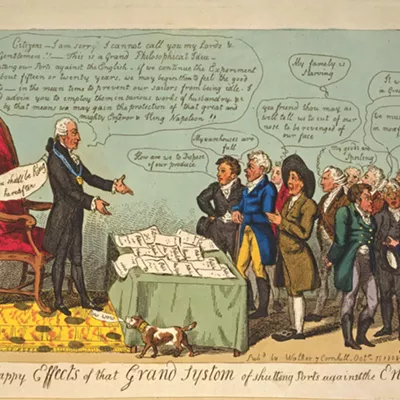

Deploying the same rhetoric that he so famously used in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson argued that it was "self evident" that "the earth belongs in usufruct to the living" in a letter to Madison in September 1789. Trained as a lawyer, Jefferson invoked the term "usufruct" from property law to explain his conviction that each living generation has the right to use the earth, but without owning it in perpetuity. In other words, he argued that each generation ought to be independent of one another. One generation had no right to bind future generations through their political or fiscal choices.

From this premise, Jefferson proposed a radical theory of generational independence. Working from demographic data, he determined that a political generation spanned 34 years from the age of adulthood at 21. From the combination of voter deaths and children reaching adulthood, Jefferson calculated that the majority of people eligible to vote in 1789 would become a minority within 19 years. That is, only half the electorate in 1808 would have been eligible to vote in 1789. Consequently, Jefferson proposed to Madison that every constitution and law "naturally expires" after 19 years. Each generation should frame its own constitution and pass its own laws, free from the constraints of the dead hand of the past.

Jefferson argued that each generation ought to be independent of one another. One generation had no right to bind future generations through their political or fiscal choices.

Jefferson never tried to enact his radical theory. But what would his ideas mean in 2024? If we use Jefferson's calculation with current demographic trends, an electoral generation today will last approximately 24 years, only five years longer than in 1789. By this measure, both Biden and Trump will be three political generations removed from first-time voters in 2024.

Jefferson did not intend to deny suffrage to senior citizens when he reflected on the independence of political generations. Nor did he advocate for denying anyone elected office based upon their advanced age. Indeed, following his own logic, we, the living, need pay no heed to someone who last dwelt on this earth almost 200 years ago!

Nevertheless, his letter to Madison does provide a frame of reference for thinking about how age plays into politics. When we consider equitable representation among different demographic groups, it is far more common in our political culture to look to race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality or religion, rather than age. Age is a moving target, driven by the relentless passage of time. But that doesn't mean that it is any less meaningful as a demographic category that should be reflected in the makeup of our representative democracy. ♦

Lawrence B.A. Hatter is an award-winning author and associate professor of early American history at Washington State University. These views are his own and do not reflect those of WSU.