It's a writing conference in a posh Idaho ski town. I know what, at least demographically, I am getting into. I'll be honest, these venues make me nervous. My reading will not be exultant or easy. My class won't ignore history or refuse to examine the difficulties of the present. I will make some people uncomfortable.

Case in point: Four weeks earlier, in Port Townsend, Washington, I read my poem "Land Acknowledgment," which was first published in the Inlander on Oct. 7, 2021. An older white male in the audience shifts in his seat. Doesn't applaud. I notice because I am watching for this. I am always interested in the ways listeners and readers respond to my work. I think about them as I am writing. When I am speaking. Their reaction lets me know if I've made my point, lost their interest, or, as in this case, hit a nerve.

The next morning, he is in my class and asks to speak to me. Alone. He tells me my poem made him uncomfortable, and he is tired of brown women's anger. I asked if he was willing to sit with that discomfort, question it. He tells me he approached another brown woman, a classmate, and told her about his reaction and she gave him the same advice. I said, "Maybe it would be easier if you sat with the reasons that compelled me to write the poem."

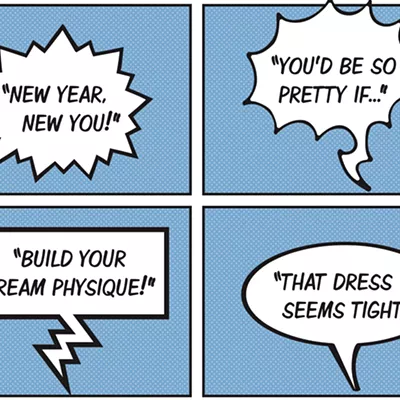

Back in Idaho, I take my seat to listen to the keynote. The title of his talk leads me to believe he will be extolling the joys of reading. The speaker has a podcast, has interviewed hundreds of writers, is quite a celebrity in this town if the size of the crowd means anything. Ten minutes in, and I realize I am not his intended audience. The books he promotes reflect his audience. They are predominantly male, white authors with stories of bootstraps pulled and incredible presidencies. He is comfortable on the stage, he knows he has engaged his listeners, he sees himself in them. But his eyes never land on me. Not even when he starts talking about a writer whose radical stance on capitalism was so crazy that he, "thought he'd gone off the reservation!"

I shift in my seat.

I hope to encourage growth, and at the very least, do my part to pull out the harmful language so deeply woven into the fabric of the dominant culture's discourse.

When I shared this story with a friend, he reminded me that the speaker was a former politician, president of a university, and how someone in those positions can easily read an audience, adapt their vernacular so as to speak in a way that makes them comfortable, makes them likely to be agreeable. Point taken. But check this out: The selection of books he was praising when he made the slur were books investigating the problems of colonization. And what his comment shows me has less to do with the speaker alone than with the pervasiveness of phrases such as "off the reservation" and its counterparts in everyday speech. If indeed his language adapted to gain approval by mirroring his audience, then that audience, many of whom laughed at the remark, is also complicit. Which points to a bigger problem that is less about the inherent meaning and more about the ease with which he passed the harmful phrase on.

If it's so pervasive, perhaps it has lost its meaning. Why not let it slide? Add it to the even more innocuous phrase, "gone off his rocker." The assumption that the later aphorism is unharmful notwithstanding, the implication of the former to a historically marginalized group is inaccurate, stereotypical and oppressive. It negates the message of the very topic he was investigating by re-colonizing fellow Americans. It points to a lack of critical thinking that is a problem in too many of our conversations. We fail to examine our language. We are not curious about the meaning of our words, only their ability to assuage and gain approval. And by continuing to use them, are we opening the door to even more damaging language?

When I am thinking about my audience, I am thinking about what they might not know. Part of writing's job, as I see it, is to offer points of view that have, too often, gone unheard. Isn't this, after all, the hope of literature? The reason we read? Not just to be validated, but to be aware? Rather than allowing the reader or listener to be comfortable with what they don't know, ignoring the harmful discourse embroidered into the very language that oppresses and limits their thinking, I hope to encourage growth, and, at the very least, do my part to pull out the harmful language so deeply woven into the fabric of the dominant culture's discourse.

I wonder how often I fail. I may have failed in Port Townsend. The man I made uncomfortable left the conference early. "You seemed so nice when I first met you," he said when the class had finished. What could I do but thank him.

As for the keynote at the writing conference? After he finished speaking, I took my place in line behind the men offering hearty handshakes and thanks, then offered my own. I said, "My name is CMarie Fuhrman. I am a mixed-race Native woman. To hear you say 'gone off the reservation' implies Native people are crazy and they belong only on reservations. It seems that you want to do work to help decolonize and educate others and certainly not perpetuate colonialism, so I would like to ask you to remove that phrase from your lexicon."

He took a step back. His smile faded. He apologized kindly, then reached for the next hand. Did I fail? I don't think so. Discomfort, after all, is the beginning of growth. ♦

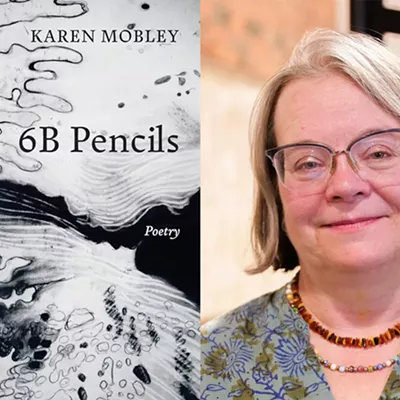

CMarie Fuhrman is the author of the collection of poems, Camped Beneath the Dam, and co-editor of two anthologies, Cascadia Field Guide and Native Voices: Indigenous Poetry, Craft, and Conversations. Fuhrman is the associate director of the graduate program in creative writing at Western Colorado University. She is the current Idaho Writer in Residence and resides in West Central Idaho. cmariefuhrman.com