"FIRST OFF," my friend wrote when I shared a picture of myself — almost 53, in wide-leg pants and a semi-cropped top — that relatives had deemed age-inappropriate and "fattening," "You know as well as I do that body comments should be off limits." I'd sent the photo to a group chat of women friends, my lifeline for both difficult moments and celebrations others might not understand. We lift each other up, a shared pulse of sanity in a culture that often tells us we're wrong.

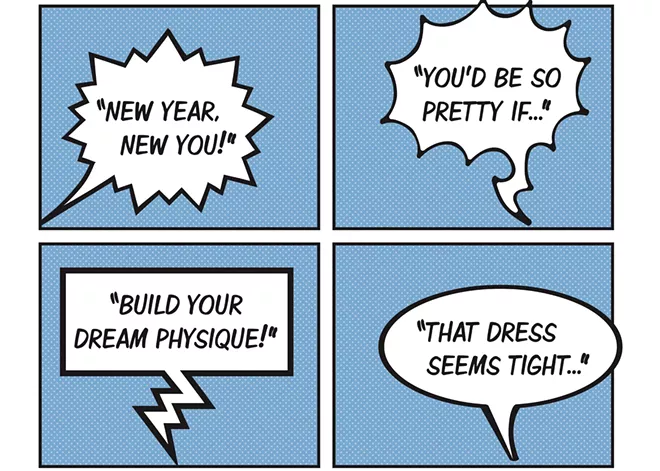

As the New Year arrived, the first messages I received — even before 2025 officially began — were about my body: unsolicited promises of finally achieving my "dream" physique, offers of minimally invasive surgeries to "suck some of me out," advice on looking younger, dressing thinner, lifting my "saggy" breasts. I instinctively pulled my thick sweater tighter around me, as if those messages could see me, were busy judging me.

I was a fat kid. I was a fat 20-something. That was the word given me by those who appointed themselves my judges. The kids who teased, adults with backhanded comments, "You would be so pretty if..." I learned to abhor mirrors — those on walls, in the eyes and mouths of others, those projected from screens, magazines and billboards. They were unavoidable. I have forgotten some of the sweeter moments of growing, but I have never forgotten the comments: "What's it like to be so fat?" "Can you even cross your legs?" The nicknames — Thunder Thighs, Tonka Tits, Walrus Woman — hateful alliteration. Kids can be cruel, I know. They find ways to tease no matter. But perhaps they learn from cruel adults. In my 20s, while riding my bike along a river one spring afternoon, trying to "get in shape," a grown man in cycling wear, leading a group of other bikers passed and muttered, "Poor bike."

"...each person's relationship with food is complex, complicated and unique."

I lost the weight, you should know. I lost a whole human. Not at first because I wanted to get healthy, but to stop being teased. To fit in. I wanted to sleep with a man who didn't say afterward that I should get a gym membership. I did extraordinarily unkind things to my body: extreme workouts, diets that included advice to eat toilet paper (yes, you read that right), fasting and cutting out all carbs before either were cool. I would have had surgeries and suction, but I was as poor as I was desperate, so all of my initiatives were self-induced.

Shame was my motivation. It should have been kindness — learning to care for this body, this home of my soul. There was no education. The role models weren't the right kind of role models. They were modeling shame and punishment rather than love and care for my body. The kind of love that would have equaled care.

This need to fit in, to be "healthy" led to first a degree and then a career in fitness. A decade later, I was, to the outside world, the picture of fitness. But I wasn't healthy. And still the comments came: My muscular arms were "man arms," my calves needed "more work," I should get surgeries for the stretch marks, the extra skin, the scars on my face. And then there were the other comments — women, you know them — the ones that terrify, that make us long for the protective layers we may have built in the first place.

If you don't know by now, you should: People gain weight for myriad reasons. My fitness career focused on working with those the medical community shamed with the label "morbidly obese." Working with these individuals affirmed what I already knew: Each person's relationship with food is complex, complicated and unique. And despite the constant barrage of information about "normal weight" and "best diets," there is no such thing. But despite all of this, the body is still not a place for public comment.

In an early attempt to find sanity with food, I joined a support group — a place for those whose relationship with eating had become a destructive force. In one of my first meetings, someone said, "At least food can't kill you like alcohol." Oh, friends. It can. The number of young women and men who have died from eating disorders — bulimia, anorexia, binging and purging, starvation — is staggering. Surgeries, fad diets (like the TikTok trend of walking 9 miles a day, eating only fruit and vegetables, or only meat, five-day cleanses topped off with a sludge of cayenne, lemon juice, and maple syrup), the pervasive shame and pressure — it never stops.

I'd love to tell you that I no longer look in the mirror and see a body that this culture rejects. Or that I don't have moments when I want to disappear, when I remember the four-hour workouts and drastic caloric restrictions that once dropped 10 pounds in a week — and landed me in the hospital — and think, maybe I could do that again. I still click on ads that promise to give me that body I had at 30, even though I know that it is all mostly empty, mostly bullshit, and even worse a way to make someone money. But I also have the therapist bills that prove the work I have done to understand my relationship with food and my body. Shelves of books about body acceptance, images of real, diverse bodies, TV shows that reflect a range of shapes and sizes. And I have a partner who never comments on bodies — his, mine, or anyone else's — except to commiserate about the shared aches of aging.

And I have this group of friends to anchor me when the shame comes roaring back from the mouths and words of others. They remind me — and all of us — that body comments are off-limits. And when I need that reminder most, I have a pink sweater we share among us. It's a superhero cape, a tangible reminder of connection and self-acceptance. It keeps all of me safe. It always fits, and when I need it to, makes me feel invincible. Because ultimately, our bodies are our own, and no one else's to judge. ♦

CMarie Fuhrman is the author of Salmon Weather: Writing from the Land of No Return (forthcoming), Camped Beneath the Dam, and co-editor of two anthologies, Cascadia Field Guide and Native Voices: Indigenous Poetry, Craft, and Conversations. Fuhrman is the associate director of the graduate program in creative writing at Western Colorado University. She resides in West Central Idaho.