Looking away from the problems of the world was never an option for the founder of the Sisters of Providence, Mother Emilie Gamelin.

Born in 1800, Emilie was already filled with empathy at age 3, when she saw a beggar and sobbed until her mother allowed her to give the man her little-girl possessions. Her own family was beset by Job-like tragedy: Her mother died when she was 4; nine of her siblings died at an early age; and when she was 14, her father died. At age 23, Emilie seemed at least to have found happiness when she married one of the leading men of Montreal.

But even then, her world slowly collapsed. Two of her children died within months of their births, and then her husband took sick and perished. A few months later, her 21-month-old son died. Just five years after her marriage, Emilie Gamelin found herself all alone.

She took comfort in caring for others. Her husband had expressed a last wish as he was dying: Would Emilie care for a mentally disabled friend after he was gone?

She did, and the care of the mentally afflicted became a lifelong concern.

But she didn’t stop there. She discovered dozens of elderly women who had outlived their families and had no place to go.

So Gamelin collected donations from her society friends and established homes for them. The epidemics that swept through Montreal had left whole families of orphans. Eventually, she was caring for more than 600 of them.

In fact, Gamelin had uncovered so many needs that, in order to cope, the bishop of Montreal established a new order of nuns. She joined and became the guiding spirit of the Sisters of Providence.

She was nursing cholera victims in 1851 when she contracted the disease and died.

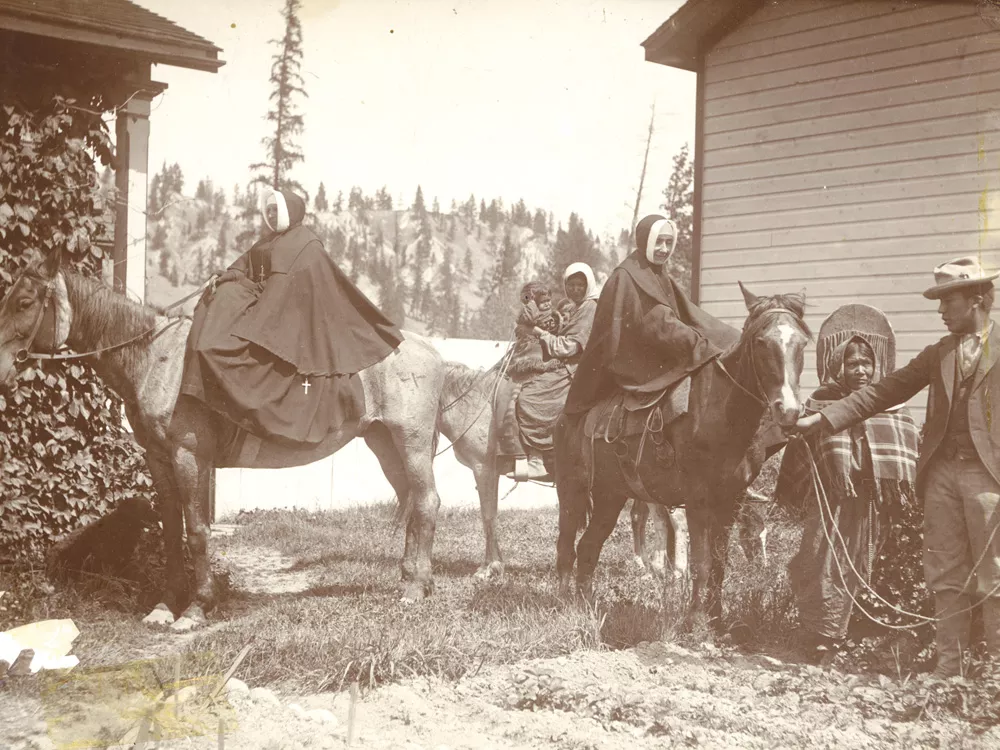

Word of the zealous Sisters of Providence spread, though, and bishops around the world sent pleas for assistance. In 1856, the bishop of Montreal responded to one of these requests by dispatching four nuns to the Pacific Northwest.

Leading this group was a close friend and confidante of Mother Gamelin, Sister Joseph of the Sacred Heart. A city girl who did not even speak English, Sister Joseph wrote back to Montreal to admit that, “with my inexperience, my unpleasant nature, my ignorance,” she felt inadequate to the task. But she also wrote a letter saying, “More and more, I feel that to be happy, I must reach out and relieve the destitute.”

She reached out, all right. Over the next 30 years, the little platoons of nuns she dispatched from the headquarters on the Columbia River traveled east as far as the Indian reservation at St. Ignatius in western Montana, and north as far as New Westminster, B.C. They created 17 hospitals (and 15 schools), including Seattle’s Providence and Spokane’s Sacred Heart hospitals.

Sacred Heart Medical Center, which celebrates its 125th anniversary this year, is a good example of Mother Joseph’s technique. In 1886, Father Joseph Cataldo, who that year was overseeing the creation of Gonzaga University, asked the sisters to build a hospital in Spokane Falls, a place being swamped by miners and settlers but sorely lacking in facilities to care for them. It was the kind of frontier outpost where the sick might die on the streets.

Mother Joseph, now 63, boarded a train with one other nun and went to Spokane. After looking over the town, she selected and purchased a site on the river between Browne and Bernard streets (where her statue can now be seen). Drawing on 30 years of experience, she sketched a brick hospital on a tablecloth, and within three weeks workmen were digging the foundation.

The imposing three-story brick building was almost complete just six months after her initial sketch; their first patient was a desperately ill man found alone in a shack in downtown Spokane. In its first year of operation, the six nuns cared for 122 patients in the hospital and made 1,040 home visits.

The hospital’s advertisement read: “Admission and Attendance Free to those Unable to Pay.” Their policy, as expressed to the staff by the nun Mother Joseph left in charge, was “to receive everyone that knocks on our door, even if we have to give up our own apartments.”

They paid for it by conducting “begging tours” to nearby towns and through the rough mining camps of the Coeur d’Alenes. It turns out their reputations had preceded them, and miners gave generously to an institution they knew was made for the likes of them.

Mother Joseph died in 1902, 46 years after arriving to take on her Pacific Northwest mission. Her last words were an echo of Mother Gamelin, “Do not say: ‘This does not concern me, let others see to them.’ My sisters, whatever concerns the poor is always our affair.”

William Stimson is the author of A View of the Falls: An Illustrated History of Spokane.