God's Gift Achiuwa, the son of a Nigerian preacher, recently decided to play his basketball at St. John’s, thus thwarting the University of Washington’s efforts to snag the best name in college sports.

To get a name with the resonance of “God’s Gift,” you have to go back to the Puritans, who gave us Faith-My-Joy as well as the somewhat grimmer names of Tribulation, Dust and Job-Raked-Out-of-the-Ashes. I find Stand-Fast- On-High more inspiring, though I don’t think I quite understand the significance of More-Fruit. My favorite Puritan name, though, has to be Fly-Fornication — a name best understood as “Fly from me, thou foul carnal temptation!” and not as a reference to flies engaged in amatory congress.

There’s a brilliance to these names, though — an aptness in the way they reflected and expressed their culture.

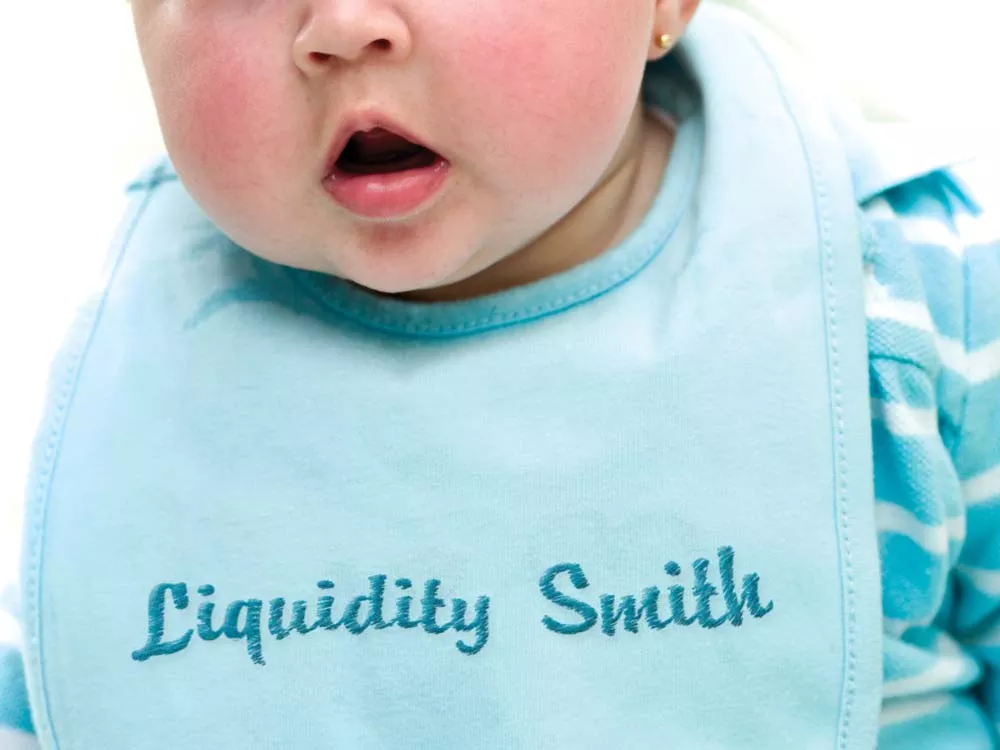

Are there equivalent names that could capture secular, millennial, late-capitalist America? Liquidity Smith, maybe?

Or, say, Appropriate Behavior Jones? How about Irony Brown?

Professor Cleveland Evans, of Nebraska’s Bellevue University, has been sifting Social Security records for a number of years, and he’s spotlighted a couple of important trends. One is naming babies after adjectives apparently valued by the populace, such as Unique and Sincere. Another is naming babies after commercial products and brands.

In 2000, according to Evans, six Ronricos, seven Courvoisiers, and 29 Skyys (after the vodka) came into the world. There were also five Darvons, as if to help with the hangover.

If you have an automotive turn of mind, you’ll be pleased to know these babies were joined by 25 Infinitis, 24 Porsches, five Celicas, and twin girls in Nebraska named Camry and Lexus. There were five girls named Disney and seven boys named Del Monte. There were 585 Armanis, 164 Nauticas, 28 Cartiers, and 21 L’Oreals. Evans noted two boys who’d been named ESPN (apparently pronounced “espen”).

Professor Evans has commented that in the 19th century, parents sometimes named their children after precious stones — Rubies, Opals — to reflect their hopes and aspirations. So, in a way, parents haven’t changed much but are just aiming for and selecting names from a richer spectrum of upscale commodities.

We may be a little behind the times in the Inland Northwest. So far this year, according to the birth announcements in the Spokesman-Review, we’ve welcomed into the world Brawk, Shyce, Tristasia, Oakly, Rowdy, Nevaeh, Cytheria, Gunner, Remington and Redbird. These babies’ names are all solid representatives of the current golden age of American names.

Nevaeh — “heaven” spelled backwards — has been a rising star, in particular. However, none of these seem all that commercial (except maybe for Remington).

But it’s never too late to change. There’s another important lesson to be learned from commercial enterprises.

Look at some of the best product names. “Viagra” is one of the best examples, a name suggesting vigor and Niagara to symbolize a powerful, irrepressible, onrushing surge.

Patagonian toothfish wasn’t a common item on the dinner plate until it became Chilean sea bass. Chinese gooseberry lagged until some whiz rechristened it kiwi, adding a dash of cuteness and New Zealand chic. The soft drink known as Bib-Label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda didn’t do much until the name was changed to … 7-Up.

And more recently (and somewhat frantically, we imagine), AIG Financial Advisors rebranded itself into SagePoint Financial.

On the other hand, you don’t have to change the name of a problematic product if it can be “repositioned” properly. Case in point: Marlboro cigarettes.

Marlboro was the beneficiary of one of the most successful advertising campaigns in history, entirely obliterating the collective memory of its previous incarnation as a ladies’ bridge-club cigarette. Early Marlboro featured a red band around the end of the cigarette to hide telltale lipstick stains. The cigarette’s motto was “Mild as May,” and it was offered in an extremely inoffensive package, the equivalent of Landlord Beige.

Marlboro poked along with less than 1 percent market share until the 1950s, when Philip Morris made its great move. Taking a cue from the trademark colors of mega-products Coca-Cola and Campbell’s Soup, Philip Morris repackaged Marlboro with brilliant, eye-catching red and white. Pumping out ad after ad, featuring Technicolor cowboys galloping across wide-screen American landscapes to the theme from The Magnificent Seven, the brand’s handlers shrugged paradox aside to turn a portrayal of rugged individualism into a triumph of mass consumerism.

Isn’t that the American lesson? When in doubt, reposition, repackage, reboot, rebrand. That’s the challenge, Generation Z, you thousands of girls named Unique, you thousands of boys named Sincere.