Stress happens. A lot. And when you’re in the eye of the tornado, it’s all you can do to keep from being sucked into the vortex of insanity. The last thing crossing your mind — as you watch your house fly away — is the fact that heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States.

But keeping stress in check is more crucial than you may have thought, since the major psychological risk factors associated with coronary disease are acute and chronic stress, hostility, and depression, according to the World Heart Federation.

Before you stress out about dying from stress, the WHF goes on to explain that “stress reduction, when in the prevention and control of high blood pressure, can reduce death by cardiovascular disease.”

So how can you tame your body’s prehistoric reaction to challenges and threats? Putting mind over matter might help.

Guided Imagery

Deborah McManus, a mental health counselor in Spokane with 20 years of practice under her belt, is like your brain’s wingman.

She practices a strand of casual hypnosis called guided imagery, where she assists patients in navigating the pictorial landscapes of cerebral topography.

That’s right — productive daydreaming.

“When I’m using guided imagery for relaxation, I find a nice, safe, relaxing place,” she says. “Really imagine that you’re there. Bring it to all the senses. Imagine there’s a little breeze. What does it feel like against your skin? Just enjoy that place for a minute or two, and then take a piece of that with you as you come back to present.”

By mentally transporting to someplace tranquil, McManus says one can gain calmness, inspiration and a sense of focus on what needs to be done next.

Sometimes she’ll have her patients imagine they’re going down a staircase, which allows the mind to tell the feet, “Hey, down there, relax!”

On other occasions, she’ll walk her clients through a scenario where they imagine cutting the ties to negative binds — like those of an ex-spouse.

The presence of McManus’s voice isn’t intrusive. It’s more a gentle conductor of meandering thought, like a tour guide leading a group of easily distracted foreigners through a beautiful, foreboding cave.

“I think one of the most useful things is bringing our mindfulness to right here, right now,” she says.

Her tone is cadent and soothing, like lapping waves against the side of a boat.

“I’m breathing in; I know I’m breathing in. Breathing out; I know I’m breathing out,” she chants, her words flowing like a clear stream.

“And if the mind wanders — because minds do that — just bring it right back to breathing in, breathing out. It’s the absolute most simplest thing we can do for ourselves.”

So the next time you feel like chucking a hammer at the source of your aggression, close your eyes and visualize last year’s vacation to Florida.

Diaphragmatic Breathing

Apparently, we’re all born breathing this way. But we stop at 18 months.

“We’re not sure why, probably because our surroundings and stress levels induce a short, shallow breathing,” says Patty Murphy, assistant aquatics director and adjunct faculty at Whitworth University.

Murphy incorporates diaphragmatic breathing into her popular Ai Chi classes, an underwater version of tai chi.

Diaphragmatic breathing is a long, deep belly breath, which engages the right side of your brain (the part that helps you slow down, relax and create.)

Fast breathing, on the other hand, incites the sympathetic nervous system — “the flight-or-fight part,” Murphy calls it.

We need both, of course. The trick is taking conscious control of airflow traffic.

To get a proper diaphragmatic breath, inhale deeply through the nostrils, until the lungs are completely filled with oxygen. The goal is to expand the belly, making the core expel all the air. The chest, on the other hand, should expand and contract as little as possible.

“It’s this great thing that gives your internal organs a really good massage,” says Murphy. “Especially the liver — that releases toxins.”

Learning how to guide your breath is a surprisingly empowering mechanism — sort of like one breath to rule them all. We’re talking long-term relief from a cornucopia of stress-related ailments: sluggish libido, back pain, tension, headaches, muscle spasms and indigestion.

“If you have a tight spot in your shoulders, for example, by taking the breath to those areas, you’re taking oxygen-needed blood there and increasing blood flow,” says Murphy. “By decreasing stress, you’re going to increase your life and good function.”

Mindful Meditation

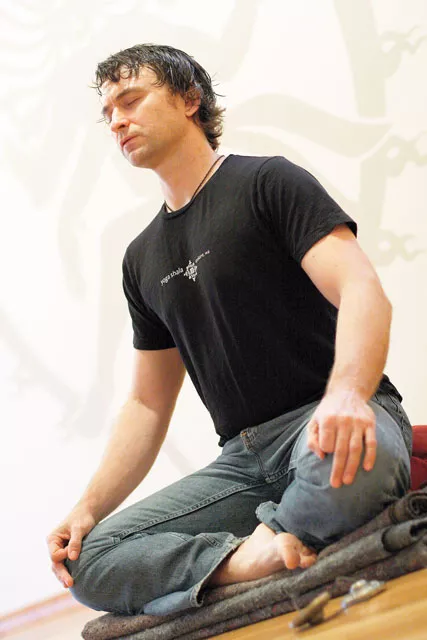

Brett Enlow, MD, an emergency physician and instructor at Yoga Shala Spokane, describes Mindful Meditation as “paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally — as if your life depended on it.”

Which sounds intense. But it’s the exact opposite.

Practicing some degree of meditation on a regular basis can increase overall wellbeing over time, as well as help to address feelings of untenable discomfort.

Just think of it as the M&M’s for the soul. (Minus the calories.)

Citing an example of practical application, Enlow says, “If I’m bothered by something, I’ll place myself somewhere where I can have a few minutes to myself.”

From that point, Enlow allows himself to just be.

“I’ll sit and ask myself: What do I feel? Where am I? What is going on? I’ll allow that to be, and breathe with it and experience it — and more often than not, it gets tired and it begins to go away,” he says.

Our net response when something upsets us, says Enlow, is to move away from it — when in fact the best thing to do is move toward the problem and allow it to be there.

Sesame Street taught us this in preschool. But then life happened.

“In our culture, it’s a little bit strange to have someone say, ‘Hey, go sit down and not do anything, and make time to do that,’” says Enlow.

He cites findings from a 2002 study, titled “Alterations in Brain and Immune Function Produced by Mindfulness Meditation,” by Richard J. Davidson, PhD, and Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD.

The study measured brain activity of two randomized, controlled groups of employees, one of which went through a meditation program.

In the end, EGG imaging of the meditation group showed significant increases in the left-sided anterior activation (a pattern associated with positive effect).

Both groups were also given a flu vaccine. The meditation group’s immune systems kicked a significantly higher amount of virus butt.

“I suggest stopping the frenetic movement every day to some degree,” says Enlow. “It will help begin to slow this whole thing down, so that each time you do something and say something, it’s intended and meaningful and thoughtful.”

Not a bad idea, since the American Institute of Stress says that 75 to 90 percent of all visits to primary care physicians are for stress-related problems.

And with stats like that, mind-timeouts should be an everyday requirement.

HOW TO BREATHE

1. Get comfortable. If you have a second, put on your elastic-waistband pants. You know — the kind you wear when you’re too full.

2. Sit or lie down.

3. Place one hand on your chest, the other on your stomach.

4. Inhale slowly through your nose. (Slowness is key.)

5. Note the expansion of your stomach as you inhale; keeping your hand on your stomach increases awareness of this. Your chest should rise as little as possible.

6. Slowly exhale through pursed lips, focusing on using your core to push all the air out.

7. Rest, then repeat.