At the Spokane Regional Health District, there are no salty or sugary snacks in the vending machine, which is instead stocked with whole wheat crackers in the shape of bunnies and organic milk to wash them down with. There's a basket that employees can drop a dollar into and pick up a piece of fruit. Employees conduct meetings while walking and work at standing desks or treadmill desks.

Every day around lunchtime at the district, a handful of employees file into a room on the building's first floor, where over pop music playing from a boom box brought by a personal trainer, they do yoga, cardio exercises and light weightlifting.

"I have no excuses because I can just run downstairs," says Rachael Oberst, family research coordinator at the SRHD. After getting a 50-minute workout, Oberst says she feels more relaxed and focused as she returns to work.

Across the country, more workplaces are starting to look more like the SRHD as companies seeking to curb rising health care costs take a new interest in the health of their employees. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey released in September, virtually all large employers (with 200 or more employees) and 73 percent of smaller firms offered some sort of a wellness plan, which, using a combination of carrots and sticks, goad employees into taking better care of themselves.

These programs differ from company to company. Some offer employees a basic assessment of their health and small financial incentive to stay healthy. Some offer a smoking cessation or weight-loss programs. More hands-on programs feature events meant to energize employees, complete with prizes and T-shirts. But how well do these programs work, and what goes into an effective one?

Buying in

Natalie Tauzin, healthy communities specialist at the SRHD, says that a successful employee wellness program creates a "culture of healthy" where the default option is the healthy option for employees. For instance, employees would naturally take the stairs to their office, and at company potlucks there would be salads and fruits present instead of heavier dishes that might provide instant gratification. But getting there isn't easy.

Tauzin says that sometimes a human resources manager or a committee interested in a program will throw out an idea, but it ends up not getting much traction due to a lack of buy-in. Buy-in from an organization's leadership is crucial to make a program work.

This is a lesson that Shari Yamane, chief human resources officer at Inland Imaging, learned when putting together the company's employee wellness program in 2009.

"If you don't have buy-in from the top it will fail, because no one is really committed to it," says Yamane. "We needed funding for it, too."

The company, which is self-insured, had seen its health care costs for roughly 400 employees rise and instituted a wellness program, in part, to keep those costs in check. Because Inland Imaging had support from the top, they had resources to sustain it.

One of the first things they did was to take a look at the current health of their employees. They hired a third-party company to collect and aggregate the data so they wouldn't violate the privacy of individual employees. The findings revealed that many had a common American health problem: They were overweight.

Yamane says that Inland Imaging had a big kickoff event where employees received T-shirts and booklets about the new program. Employees could participate in challenges to see who could lose the most weight or increase their activity level. Winners would receive yoga mats or gym memberships. Inland Imaging also set up a small gym in its basement and started offering yoga and Zumba — an aerobic exercise style that incorporates dance elements — classes to employees.

Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center, in the midst of setting up its employee wellness program, learned early on that it's also important to have buy-in from employees. Last year, it launched stress reduction and healthy eating programs along with Pilates as part of the program. But participation was "less than wonderful," says Jane Mather, director of the hospital's Center for Health & Well-Being and Spiritual Care Services.

"It can't be driven from here," says Mather, referring to management offices. "It can start here, but it's got to be a groundswell."

Mather points out that many employees, nurses in particular, are busy attending to patients and might not check email or bulletin boards to find out about wellness offerings. Currently, the hospital is conducting focus groups to see what works and what doesn't.

Keith Campbell, professor emeritus in the pharmacotherapy department at Washington State University, says that effectively marketing a program to employees is a fairly common problem for organizations, particularly small companies.

Sticks versus carrots

Tauzin, at the Spokane Regional Health District, says that an employee wellness program shouldn't be based on "you do this or else." She says that programs should instead try to positively motivate employees to take charge of their health. But it does help, she says, if "employees have some skin in the game."

It's a tricky balance. Employers want their employees to be healthy so they will show up to work and not run up medical costs. But some employees have resisted efforts by their companies to direct their health.

If employers use too much stick, they could find themselves facing a lawsuit. Last year, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission took legal action against several companies who mandated that employees undergo health screenings as part of their programs and then significantly shifted the cost of benefits onto workers who objected to being required to participate.

Yamane says that the wellness program at Inland Imaging has primarily relied on incentives to encourage participation.

"This is the first year where we've gone with some of the sticks as well as the carrot," she says.

The company pays for the full health care costs of its employees, but this year workers will have to complete a biometric exam and health risk assessment, which provide a snapshot of someone's health. If they don't, they'll lose out on a small contribution to their health plan. Also beginning this year, employees are given a small financial incentive to their health care costs, one that they won't get if they are a smoker.

"We had a couple really angry smokers," she says. "But, then again, there is so much data out there saying that if you are a smoker, the chance of getting cancer is so high."

Smokers who undergo a cessation program and sign an affidavit that they have quit smoking can be reimbursed at the end of the year, she says.

Campbell agrees that employers should rely more on carrots rather than sticks to get employees to participate, and should try to make the program fun.

What is wellness?

Some programs seek to go beyond simple metrics such as blood pressure or body mass index to a more holistic approach.

At Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center, the employee wellness program will take into account a spiritual dimension, says Mather.

"It's not about religion," says Mather. "It's how do you find meaning and purpose."

In a particularly challenging environment, such as a hospital, many employees may be emotionally taxed after coming home from work. Mather says the program wants to make sure that employees get the support they need so they won't feel emotionally or spiritually drained from work.

The Spokane Regional Health District's wellness program also seeks a more holistic approach to employee health. To that end, says Tauzin, the district seeks to create an atmosphere that takes into account the social and mental health of employees. If employees are energized, "that hits your bottom line very quickly," she says.

The academic research on whether or not employee wellness programs work is mixed. Some studies and larger corporations have found that these programs can indeed save money. Last year, a study from the RAND Corporation found that programs aimed at reducing the costs associated with chronic illnesses can work. But it cast doubt on elements of these programs aimed at encouraging employees to adopt healthier lifestyles.

People who have helped design and implement them are convinced otherwise. Yamane says that her program has helped keep health care costs down and has made a difference in employees' lives.

She recalls one employee who won a weight-loss challenge. The employee, in his 40s, became more concerned with his health and even ran a marathon. This person, says Yamane, will likely never be overweight again thanks to the wellness program.

"That's huge," she says. "That's a whole lifestyle change." ♦

Stand Up for Your Health

Mary Prince, manager of corporate benefits for local power company Avista, which offers a basic wellness program, says that employees who have desk jobs are more at risk for health problems than those who have physical jobs.

"One thing that's kind of interesting is that among our employees who have the sedentary jobs, [their] health is not as good as those who have the physical activity in their job," she says, noting that the company's emphasis on safety guards against injury for those with more physical jobs.

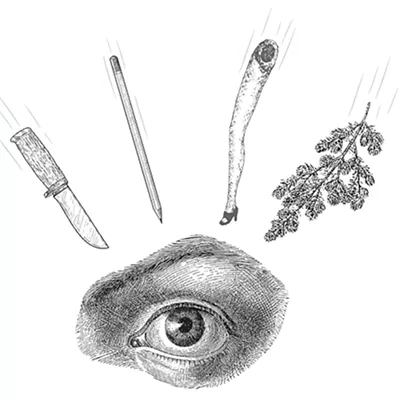

Over the years, a steady stream of academic studies have discovered that sitting all day can invite a host of health problems, from disability to cancer to early death. Even regular exercise, research has found, can't undo the harms of sitting all day.

"It undoes that because we are so sedentary," say Natalie Tauzin, healthy communities specialist at the Spokane Regional Health District.

Standing desks are becoming common at many workplaces. Some, like SRHD, have even adopted treadmill desks, where employees walk while working. Others encourage employees to have walking meetings to get employees on their feet. The Huffington Post recently reported on a Dutch art installation called "The End of Sitting," a hypothetical work environment where it was impossible to sit and employees could only stand or lean.

"Our art installation isn't an answer to the sitting problem," says Ronald Rietveld of Rietveld Architecture-Art-Affordances in Holland, "but is a radical proposal to make people aware and to challenge them to start thinking in a different way about our working environment."