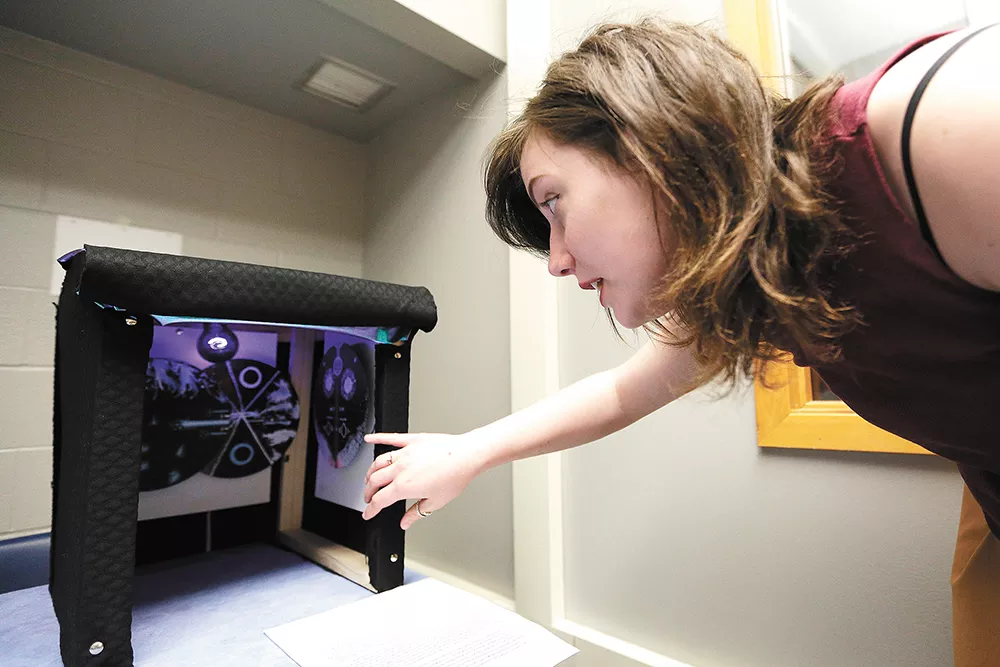

Dean Strouse didn't use any beakers, flasks or Bunsen burners for her chemistry project at the Community School. Instead, Strouse created a piece of art.

It's a black box lit up with ultraviolet light. Inside, paintings symbolize hydrogen peroxide reacting with luminol, a chemical that glows blue to help detect traces of blood at crime scenes. It may not be the kind of project that other science classes would accept. But at the Community School, teachers hope that Strouse and her classmates will understand concepts of chemistry more deeply through art and poetry than if they had learned in a more traditional way.

"I think this really gives us a way to apply ourselves," Strouse says. "This project in particular made us interested in chemistry. They make it fun while we're learning, and we still have all the standards that other schools do."

The Community School uses what's called "project-based learning" as its main teaching method. In project-based learning classes, students come to understand certain subjects by investigating a complex question, problem or challenge, before demonstrating their knowledge with some kind of project.

It's not a radically new concept, but it's one that's gaining momentum. And the project of communicating chemistry through art — subjects that traditionally had little to do with one another — encapsulates much of the debate surrounding project-based learning, or PBL.

The research on the effectiveness of PBL is mixed, and the method can create an extra strain on teachers. Yet students consistently report being more engaged with this type of learning, and it can help them with collaboration and teamwork skills that pay off down the road in college and in the work environment.

In Spokane, schools are increasingly using project-based learning as a teaching tool, and it's starting to spill into more traditional schools. Ferris High School, with more than 1,500 students, started a PBL program that started with 12 students a year and a half ago, but already plans to enroll 200 students this fall.

"It's an instructional strategy that, if done well, can really help illuminate a student's understanding of a topic, in a way that a traditional test may not," says Steven Gering, Spokane Public Schools' Chief Innovation and Research Officer.

TEACHING WHAT MATTERS

Project-based learning in Spokane Public Schools started as a way to reach kids who weren't responding to traditional teaching methods, the kind that involve more lectures, more sitting in a classroom, and more memorization.

That was the kind of environment that Emma Linklater, a junior at the Community School, wasn't responding to during her freshman year at a traditional public high school.

"I got bored, going to class after class," Linklater says. "I felt like I wasn't doing anything that mattered. I was doing worksheets and worksheets, and it was useless."

At the Community School, she says the work feels more applicable to real life. The school, part of Spokane Public Schools, was founded in 2011, and moved to its current location in 2013. It uses a national model for project-based learning, and currently has 157 students. Other PBL schools in the area include Spokane charter school PRIDE Prep, Mead's Riverpoint Academy and West Valley City School.

Schools across the globe have similar ideas. In New Zealand, a charter school called South Auckland Middle School integrates curriculum and, like the Community School, often incorporates art into the projects.

Project-based learning, in Spokane and around the world, isn't an idea that has been adopted by entire school systems. Rather, it emerges from the ground up in different pockets, says David Hutchison, a professor of teacher education at Brock University in Ontario.

"I think project-based learning comes with tremendous opportunity," Hutchison says. "But it also has great risks attached to it."

Advocates of PBL say it allows students to take control of their own education. Critics, however, argue that there's value in teachers doing more traditional teaching. In 2006, three educational scholars — Paul Kirschner, John Sweller and Richard Clark — published a paper in the journal Educational Psychologist arguing that minimal guidance during instruction does not work.

Spokane Public Schools' Gering says that project-based learning works best in conjunction with other traditional methods. If a teacher were to pull someone off the street and give them a project, offering no other instruction, and the person could do it, then it's probably a bad project. Ideally, projects could demonstrate something a student has just learned.

Hutchison agrees. If poorly managed, he says that students would only scratch the surface when learning about a given topic. But a project that incorporates different subjects, like expressing chemistry through art, can be a rewarding experience for students. He says research has shown that one of the most effective ways to learn is when students can challenge themselves by connecting new information with things they already know.

"I think that's where the rich learning happens, in finding those connections," Hutchison says.

Tami Linane-Booey, a teacher at the Community School, says she is teaching there because, in her view, project-based learning can help reform education as a whole. Teachers are no longer training people to be factory workers, and no longer do students need to memorize information the way they used to.

"A lot of people are trying to figure out how to fix education," she says. "We all kind of agree that it's broken, but we don't all agree on how to fix it. And the problem is, there is not one way to fix it, because every kid is different."

So far, students at the Community School have done well above average on English and language arts state tests, but not so well on math. Students use a web-based math program at the Community School, not project-based learning. But Linane-Booey says the skills her students can use down the road far outweigh any negatives.

"We want students to work with others, think critically, think outside the box, and be lifelong learners, and know that you can teach yourself anything you want to learn," she says. "And that is, for me, the power of project-based learning."

SCHOOL WITHIN A SCHOOL

At Ferris High School, assistant principal Sammy Anderson saw for herself that a number of kids just weren't involved in school. They'd come to school but not go to class, or they'd go to class and not care.

But rather than tell those kids about another school better suited for them, Ferris decided to provide its own option for kids: a project-based school within the school. This school year, 40 students took the program. Next year, Ferris is expecting up to five times that number.

"We like the school-within-a-school model, because then students have access to our excellent music program, or our drama, or debate," Anderson says. "I think that's one of the cool things about a comprehensive school — to go to our [convocations], to be in leadership class, and then have this other option within the day that is project-based."

From a teacher's perspective, the project-based classroom can be both invigorating and challenging, says English teacher Emily Torres, who has taught at Ferris for 15 years. While classroom instruction may not be as intensive, coming up with a curriculum and projects can be time-consuming.

"I'd be lying if I said it wasn't a lot of work," she says. "I was ready for a challenge, and certainly got it."

Gering says Spokane Public Schools will continue to train teachers in the project-based method of teaching, if the teachers want it. He doesn't see project-based learning as the "end all, be all," but as a tool that some people can use to help demonstrate learning.

Even believers in this method, like Linane-Booey, don't think it should be forced on all schools.

"We have to stop saying, 'Every kid fits in this box and we're all going to learn this way,'" she says. "So as we're developing that, we're developing more choices. And the district is behind choices and different ways of learning." ♦