Things are not looking good for this year's wildfire season, with hot weather, rapidly melting snowpack and a smaller fire season last year stacking the deck in the flame's favor.

The Inland Northwest just had its hottest May on record, with an average temperature of 63.5 degrees (beating the normal average for June of 62.4 degrees, according to National Weather Service data), and this summer is expected to be hotter than normal. The region has also had lower than normal precipitation each month this year so far, which means drier soils.

While the harsh winter stacked up more than the average snowpack, more than half of that has already melted.

On June 15, the Spokane River was flowing at 4,340 cubic feet per second by 1 pm, which was about half of the normal level, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The record low for that day happened in 2015, when the river was at just 1,220 cubic feet per second.

Last year's fire season in Washington state saw the third-lowest number of acres burned in the past decade, which may have left shrubs and grasses from 2022's very wet spring and summer ready to fuel fires this year, says Thomas Kyle-Milward, a spokesman for the state Department of Natural Resources.

"Some [recent years] have been the worst fire seasons in recorded history," Kyle-Milward says. "By all accounts this year will be another one of those years, and not like last year's anomaly."

Fires have already started popping up across Eastern Washington, and all of Washington and parts of North Idaho are forecast to have above normal risk for significant wildfires by July, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.

The good news is, investments in new technology and equipment and changes to firefighting and prevention are in the works. While some of those changes won't happen this fire season, they could make future years more bearable.

EYES IN THE SKY

One of DNR's newest investments will use artificial intelligence to help spot fires on state-owned lands faster and get firefighters where they need to go.

Earlier this spring, the department announced a pilot project with Pano AI, a technology company based in California that was created to help combine 360-degree camera technology with detailed mapping and GPS data.

Under the agreement, Pano AI is putting 21 different cameras in critical places (usually on mountaintop cell phone towers) around the state to help spot fires. About half of those will be stationed east of the Cascades in Central and Northeast Washington.

The system works by taking a series of pictures that can be stitched into a full 360-degree view of an area every minute. The data is then sent through Pano's AI, which is trained to spot smoke and hot spots at night with infrared imaging.

With cameras strategically stationed, the exact location of fires can be triangulated or paired with GPS data to help approximate the location.

When an incident is flagged by the computer, humans review the images to confirm and relay that information to fire departments, says Sonia Kastner, CEO and founder of Pano AI.

The idea for the company came to Kastner after working at the security camera company Nest and living in California through disastrous wildfire seasons.

"I was looking for ways I could use the technology I was aware of in Silicon Valley to make natural disasters less harmful," Kastner says. "The tools that firefighters are using have not evolved rapidly over the last 30 years, but the challenge is getting worse and worse. ... We need modern technology."

The Pano AI reports may include a timelapse video so responders can see how it's behaving and other helpful map data, such as the location of nearby water resources.

"The goal is to coordinate an aggressive response," Kastner says. "We've designed our solution to facilitate a new trend in firefighting called rapid initial attack, where firefighting agencies and city, county, state, and federal agencies collaborate very quickly, like in the first hour, where it's only five or 10 acres."

George Geissler, Washington state's forester and supervisor of wildfire operations, says the goal of the one-year pilot is to see how well the cameras integrate with the detailed information systems the state already uses, and how they affect response times.

"Really the next big thing for us is the ability to not only get to a fire quicker but find those fires faster," Geissler says.

WATER IN THE SKY

Another move that could soon help attack fires while they're small passed through the Washington Legislature this year, after state Rep. Mary Dye, R-Pomeroy, spent seven years trying to get it to the finish line.

House Bill 1498 will enable local fire departments or districts to call in air resources to dump water before a blaze has grown so large that it requires a full mobilization of state resources.

Dye says she's been fighting for the bill for years at the urging of small local fire districts in the rural areas she represents, including Adams, Asotin, Franklin, Garfield and Whitman counties, as well as some parts of Spokane County.

The fire that inspired the initial version of the bill started out small in Asotin County. As the chief in that area tried to get approval to fly in aircraft, playing phone tag all day as crews fought the fire with brush trucks on the ground, the blaze grew, Dye says. Air resources that were initially denied were ultimately called in after the fire grew so large it required a state-level mobilization of firefighting resources.

"It's clear the system is broken," Dye says. "If they could just call out a couple of dumps of water with that air service, they could reduce the number of catastrophic fires we experience each summer. But the shot gets called from Olympia, not our local fire service."

The new law will change that, but not until next fire season.

This year, DNR will create a program to register those smaller departments and ensure they've got the training on how and when to call in air resources. Once that's in place, those departments can call in approved contractors and then notify the state, rather than waiting around for air support approval.

"If you give them an effective tool, they can do a lot with a little and stop a lot of the catastrophic state mobilization fires," Dye says, noting that in some cases where aircraft were available right away, the costs were kept to a few thousand dollars, rather than the millions of dollars that megafires cost to battle.

In a compromise to help get the bill passed into law, it includes a sunset, expiring in July 2027. By then, the idea is that the state will have enough data on how the new protocol has been working to know if it's helpful.

SMOKE (DETECTORS) IN THE SKY

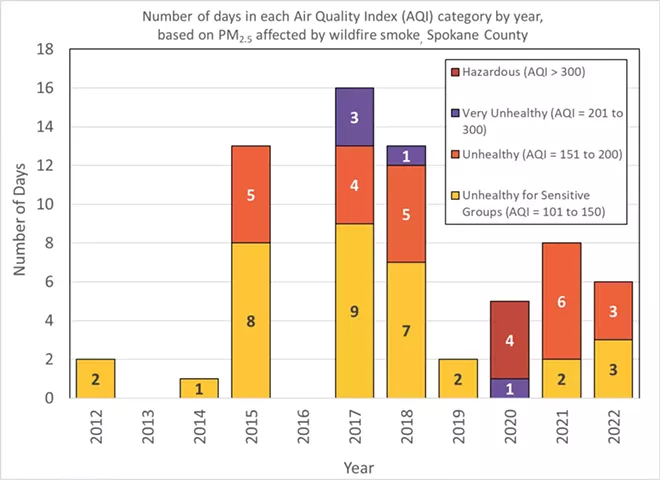

While some on the West Coast have been less than sympathetic in recent weeks as the East Coast has struggled for the first time with hazardous air quality from wildfire smoke, sparking dozens of stories about things like the Air Quality Index, it's likely the Pacific Northwest will experience the dreaded smoke season again, too.

The Spokane Regional Clean Air Agency, Spokane Regional Health District, Spokane County Emergency Management and other partners started getting the word out last week during "Smoke Ready Week."

SMOKE SEASON RESOURCES

AIR QUALITY AND SMOKE: airnow.gov, spokanecleanair.org, wasmoke.blogspot.com

FIRES: gacc.nifc.gov/nwcc

RESOURCES: srhd.org, doh.wa.gov, spokanecounty.org/3007/Alert-Spokane

Their advice echoes that of recent years. When air quality starts to diminish, sensitive groups like children, the elderly and those with health conditions are the first to be told to stay inside. As more damaging particles fill the air, the Air Quality Index rises, and everyone's health can be at risk.

To stay safe indoors, the agencies encourage people to have HEPA air filters that can run in at least one room of their home or to create their own by attaching a furnace filter to a box fan to pull smoke particles out of the indoor air. N95 masks can also help, but the first step should be to get out of the smoke, says Lisa Woodard, spokeswoman for the Clean Air Agency.

Just as air conditioning units and box fans fly off shelves during the first days of a heatwave, those filters can sell out during the first bad wave of smoke, so the agencies are encouraging people to prepare early.

This year, Spokane will also get more air quality monitoring technology.

Spokane/Spokane Valley was selected as one of 16 overburdened Washington communities that will receive air quality investments under the state's Climate Commitment Act.

This region is scheduled to get one more regulatory-grade air quality sensor, adding more valuable information to the three regulatory sensors already in place around Spokane County. The state Department of Ecology will also install five more low-cost sensors that can help track more granular data about the pollution experienced in specific neighborhoods.

Households within the boundaries of the overburdened community map will be getting snail mail from Ecology this summer so people can weigh in on where those low-cost sensors should be placed, says Susan Woodward, communications manager for Ecology's Air Quality Program.

The plan is to install the new sensors by year's end.

PIE IN THE SKY

Since 1947, Smokey Bear has been telling anyone who will listen that "Only YOU can prevent forest fires." While that was updated in 2001 to "Only you can prevent wildfires," the underlying message hasn't changed.

That's because one of the harshest truths about wildfires is that human activity causes 81 percent of them.

Common causes include electric utility equipment, fireworks, campfire pits that are left too hot and spark back up again, people driving vehicles over tall grasses or using equipment in dry areas, cigarette butts, garbage burning, and arson.

Natural causes like lightning strikes start only about 15 percent of wildfires, according to data gathered by Challenge Seattle, a coalition of business and tech leaders in Washington.

While fighting fires makes sense to protect people and their homes, fire experts note that it's important to remember the Western landscape evolved naturally to include fires, with some plants even requiring fire to germinate. Indigenous peoples understood the dynamics and sometimes started fires to aid in the natural process.

But a century of firefighting efforts (and some conservation efforts) have changed the landscape for the worse, with smaller trees and fuels that would normally burn filling the forest floors with tinder, making it more likely that larger trees burn. Strategies are changing due to that knowledge.

DNR, which was allocated $500 million in 2021 to prevent and prepare for wildfires over the next eight years, is using some of that money to help communities make properties less susceptible to fire. The agency is also mechanically thinning forests to eliminate fuels, and in some cases operating prescribed burns, Kyle-Milward says.

In the meantime, DNR will deploy new equipment this season. The new resources include two fixed-wing aircraft with infrared and other scanning technology that can help map fires and send that information to crews on the ground, as well as 16 heavy dozers and four excavators.

Washington also received $39 million from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2022 to spend over the next five years to mitigate wildfires.

As Smokey points out, everyone can help by following burn bans, forgoing fireworks, properly disposing of cigarette butts and matches, and leaving their fire pits extinguished and cool enough for the ashes to be picked up. ♦