Arthur Longworth's dog-eared manuscript was inconspicuously shuffled among the other essays that the volunteer English teacher had to grade. Held together with a thick black clip, the tattered document had yet to be read by anyone beyond prison walls.

That night, as Marc Barrington sat in bed reading Longworth's fictional account of a single day in prison, he felt overwhelmed by one thought: People need to read this. For more than a year, Barrington grappled with whether to publicize the inmate's words. Doing so could jeopardize his position as an instructor in the prison and potentially the entire program, he thought.

In addition, the Washington Department of Corrections had already caught Longworth trying to send his novel to his ex-wife more than a decade ago. Longworth says he was sent to solitary for months as punishment.

Ultimately, Barrington decided the story was too good, too important to not see the light of day, and shopped it around to publishers.

"The people I spoke with in New York said it was good, but they couldn't market it," he says. "I thought, 'That's bullshit.'"

In June, Barrington published the novel himself, under the Seattle-based company he had started intending to publish his own novel.

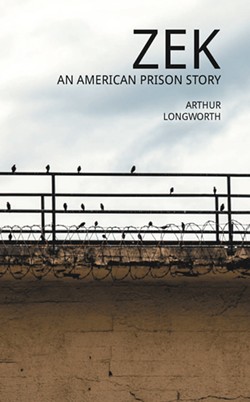

Zek: An American Prison Story chronicles a day in the life of the young inmate, Jonny Anderson, while he's locked in the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. Inspired by the real story of a Spokane high school student who fired a gun in a local school in 2003, Longworth says, the manuscript circulated throughout Washington state prisons for more than a decade.

A tall, thin man with blonde hair, Longworth is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole for an aggravated murder he committed in Snohomish County when he was 20. He has become a prominent voice on life inside, publishing a collection of essays and articles, and has won national awards for his writing, including the PEN Center's Best Prison Memoir in 2010.

His most recent novel, however, has the Washington DOC grappling with its internal policies and inmates' constitutional rights. Copies of Longworth's manuscript have been destroyed in the past, he says, and a review panel has officially barred inmates from reading it.

"I do wonder when prison officials will surrender," Longworth writes via email. "I mean, when they will cease viewing my writing as a hostile act? If prison was really about what it's supposed to be — that is, correcting people, reforming them, helping them to become better than they were when they were sent here — then they should be proud of me and what I've done. Unfortunately, I don't get that sense."

Back in 2005, when Longworth first finished his novel, prison officials caught him trying to send a copy to his ex-wife. For that, he says, he was sent to solitary confinement for months, although a DOC spokesman could not confirm any sanction.

The questions of whether an inmate has the right to publish a book, and if that book should be allowed inside prison walls, is one that pits prisoners' First Amendment rights against DOC's interest in maintaining a safe environment.

A U.S. Supreme Court case from 1987 still holds precedent. Turner v. Safley established that prisoners have limited freedom of expression. And prison officials have wide discretion, says Ken Paulson, president of the First Amendment Center in Tennessee.

"It's a very low bar," he says. "And as long as prison officials can, with a straight face, say this is a matter of security, courts will almost always side with them."

Washington state prisons, for example, ban titles such as French Made Simple, (because the book contains "dual language,") Field & Stream magazine (because it contains images of weapons) and The Complete Art of Tattooing (because it contains "instruction on how to make a tattoo gun").

DOC's mailroom employees make the initial decision on which material inmates are allowed to have. If they reject something, the three-member Publication Review Board meets once a month for a final decision.

As is the case throughout the country, that decision-making appears arbitrary. Both the Compendium of Contemporary Weapons and Mein Kampf are apparently not banned, according to the list of banned and permitted materials on the Washington DOC website.

As for Longworth's novel, prison officials banned the book in part over concern that its details could provide a "how-to" regarding transferring contraband, DOC spokesman Jeremy Barclay writes via email.

Interestingly, Barrington, the English teacher, points to the book listed directly above Longworth's on the list of banned and permitted materials. Christopher Murray's book Unusual Punishment: Inside the Walla Walla Prison 1970-1988 includes "aerial photographs of the prison layout," details about "crafting weapons/bombs," "manipulation of staff," "escape" and "hostage situations," yet inmates in Washington are allowed to read it.

Barrington questions whether Murray's connection to the Department of Corrections as an architect and through another state department has anything to do with the apparent discrepancy.

Although it's reasonable, Paulson says, for prisons to withhold literature that could endanger officers and inmates, he sees no legitimate reason to censor information coming from inside prison walls to the general public. The effort of inmates to tell those on the outside what it's like behind bars is essential.

"It would be absolutely wrong for the prison system to punish [Longworth] for exercising his constitutional rights," he says. "What if a prisoner could document corrupt behavior inside the prison? Wouldn't we want them to have the full liberty to tell the outside world what's going on? Surely that would be protected."

In 2003, a 16-year-old walked into Lewis and Clark High School and fired a single shot. Spokane police tried to negotiate with Sean Fitzpatrick, but the boy ended up shot three times when he raised the gun toward the wall of officers.

Media outlets debated what impact a long prison sentence would have on a teenager.

"People weren't sure what would happen to him if he got that 12-to-15-year sentence," Longworth says. "But we knew exactly what would become of this young man."

That debate was the impetus for Longworth's novel. From his cell in the Washington State Penitentiary, he wrote a story about a single day in the life of Jonny Anderson. The 186-page book follows the 20-something inmate as he witnesses another inmate burned alive in a cell, as he stands watch while one inmate sexually assaults another, and while he cleans up blood and teeth after officers viciously beat another inmate.

But beyond the descriptions of brutal physicality associated with prison life, Longworth's novel strikes an emotional chord. Jonny lies in letters to his mother to protect her from the realities of prison life. As the end of his sentence approaches, he wonders how — and if — he'll survive on the outside. All he knows is prison.

"It was written for prisoners, and they believe in that book," Longworth says. "They'll take risks to hold onto it. It narrates a story that doesn't exist anywhere else." ♦