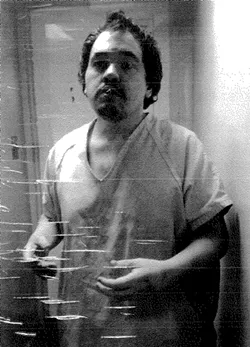

Eyvonne Bercier can tell when her son hasn't been taking his medication. He jumps from one topic to the next, and often doesn't make sense. When it gets really bad, the voices that creep in and out of his mind stay longer and speak louder. They say they're going to kill him, he starts to hallucinate, and he doesn't sleep for days. Sometimes he thinks his mom is trying to kill him.

This is what was happening before Shawn Rettinger was arrested on April 1, according to court documents. Recently, Rettinger's doctors took him off lorazepam, one of the medications he had been taking for 12 years, and switched his antipsychotics. Then the voices grew louder, and he threw away any new pills his mother gave him. He thought they were poison.

Worried about her son, who is diagnosed with schizophrenia and was civilly committed 13 times between 2001 and 2015, Bercier took him to the psychiatric ward at Sacred Heart Medical Center. Again, he was committed for treatment at Eastern State Hospital, but before Rettinger was transferred, he allegedly assaulted a hospital worker and was thrown in Spokane County Jail. The voices grew louder still.

For 110 days, Rettinger sat in a cell by himself, only allowed out for a hour every other day, Bercier says. If he was let out on a Friday, for example, he wouldn't come out again until the following Tuesday. According to nurses' notes from the jail, Rettinger was receiving Ativan, but he didn't always take it.

"He's really far gone now," says Bercier, who last visited her son a few days ago. "He's deteriorating in there. I can tell he's getting worse and worse every day."

On April 20, Rettinger's public defender, Kari Reardon, requested a mental health evaluation to determine if Rettinger is competent to stand trial. Originally, Eastern State said that the end of June was the soonest they could evaluate him. The Inlander has previously written about the length of time it takes to complete competency evaluations in Washington, after Amanda Cook hung herself in December 2013 while awaiting an evaluation in jail. State law requires that evaluations be completed within seven days of the court order. Cook was waiting for more than 30 days when she took her own life.

But it's not as simple as getting an evaluation. The pipeline from jails to mental health treatment facilities is clogged at every step. Once an evaluation is completed, defendants must wait for a bed to open up. Despite the state law that says defendants must be transferred within seven days, many are left to languish in jails for upward of 100 days.

In April, U.S. District Judge Marsha Pechman ruled that the Department of Social and Health Services must start obeying the law. The class-action suit against DSHS, the state department responsible for providing competency evaluations and restoration services, alleged years of ignoring the seven-day wait period.

"It's like, my clients have to follow the law, but Eastern doesn't have to?" Reardon asks. She has several clients either waiting for an evaluation or a bed, all of whom have been waiting for more than seven days. She likens the department's noncompliance with the law to torture.

DSHS was given until the beginning of 2016 to hire more evaluators and add more beds. A long-term plan submitted to the court on July 2 says Eastern State will add five forensic evaluators to its staff of six and 15 beds, bringing its total to 37. Western State Hospital will add eight evaluators to a current staff of 26 and 45 more beds, totaling 161. Funding for the 13 new evaluators and 60 new beds between the two hospitals comes from the $40.5 million that the state legislature gave DSHS in June.

Reardon says the long-term plan looks good on paper, but until it's implemented, she's still skeptical.

"There have been significant improvements made in Western Washington," she says. "But they're not happening here. There's a population difference, but that doesn't make the mentally ill here less in need of treatment. I have hope that this will work."

Pechman's ruling in April also called for more collaboration among prosecutors, defense attorneys, jail employees and the courts — something Reardon says could have helped Rettinger.

"Judge Pechman's ruling says prosecutors are supposed to make tough decisions about what they charge," she says. "Does it make sense to charge somebody who's in a psychiatric ward awaiting transfer to another mental health hospital for further treatment and stick them in jail for 105 days? That's one of those tough charging decisions that shouldn't have been charged."

She's moving to dismiss the charge against Rettinger.

A lack of bed space at Eastern State isn't entirely to blame. Another one of Reardon's clients, also a diagnosed schizophrenic, waited for a total of 140 days in the jail, 84 of which were after he was ordered to be transferred for treatment. The reason, Reardon says, is because the jail only used to transport people on Mondays and Fridays. Since it takes two days to admit a patient, Eastern State only schedules transfers Monday through Thursday.

"If a bed becomes available, but a jail says they can't get the person here for another week, then we have to offer it to the next person," says Bonnie Bush, who works on scheduling and admissions in the administrative office at Eastern State.

Sgt. Tom Hill, the supervisor of the jail's medical unit, says he isn't aware of any delays in treatment because of the transport schedule, but notes that he met with Eastern State last week to come up with a system that fits both facilities' schedules.

"Right now we're transporting three or four at a time," Hill says. "But that's hard on them in terms of manpower. They'd rather take one or two at a time. So we're looking at [transporting] on more days."

Rettinger was transferred to Eastern State Hospital last Monday, though his mother worries it's too late.

"Jail is not the place for people with mental illnesses," Bercier says. "You put them in jail and they deteriorate more and more and more."

She talked with her son every day he was allowed out of his cell. With each phone call, Bercier could tell he was getting worse. He frequently said that someone was in his cell keeping him awake and trying to kill him. With each conversation, his comprehension of where he was and why he was there disappeared.

The fear got so great one night that he refused to return to his cell, so detention officers tased him. Had he been in the hospital, he wouldn't be locked in a cell all day or tased and handcuffed for misbehaving.

"No disrespect to the jail, but they're a jail," Reardon says. "I think they do the best with what they can, but the amount of time he's had to wait is egregious. It's just not acceptable." ♦