Al Hadlock was scared. Things were falling apart around him. His wife kicked him out. He lost his job. And he knew if he did this — if he robbed this bank — it would only get worse. But he was numb. Confused. Desperate. And so Hadlock walked through the doors of BankOne.

He approached the nearest teller and lifted his shirt, exposing a gun tucked in his waistband. He was too nervous to speak. So he slid a deposit slip across the counter. On it, he’d written “GIVE ME THE MONEY.”

Slowly, the young teller started to unload the drawer in front of her. But Hadlock was jittery. So he grabbed the wad of money out of her hands, shoved it in his pocket and walked — slowly, casually — out the door.

Then he started running. And for the next 40 days, as he held up 29 more businesses, he kept running. From the police, but also from everything he used to be: the happy husband and father; the loving son and brother; the star athlete; the decorated Army Ranger.

Most of his life, he had done everything right.

Then, at age 36, he decided to do everything wrong.

Big Man on Campus

Beth Harris is half the size of Hadlock, her youngest son, but she can easily make him blush. She smiles as she talks about his days at North Pines Middle School in the Spokane Valley.

“He actually changed a lot of the way they dressed at North Pines because he was a dresser,” Harris says.

“A dresser? Thanks … thanks for embarrassing me, Mom,” Hadlock, now 42, says, shaking his head.

“You are a dresser! He started getting the kids to come in clean and neat,” she says. “The junior high principal came to me and said, ‘You know, he’s just amazing.’”

She’s proud to talk about her son, who lives with her and her husband, Jack Jenks, in a tiny two-bedroom house filled with Betty Boop memorabilia in north Spokane. Harris and her sons (Al and his older brother, Tony) settled in Spokane Valley in the late ’70s. She and their father, Arthur, had separated when Al was 2. She later married Bob Hadlock, a long-haul trucker. Al says Bob wasn’t around much when he was growing up.

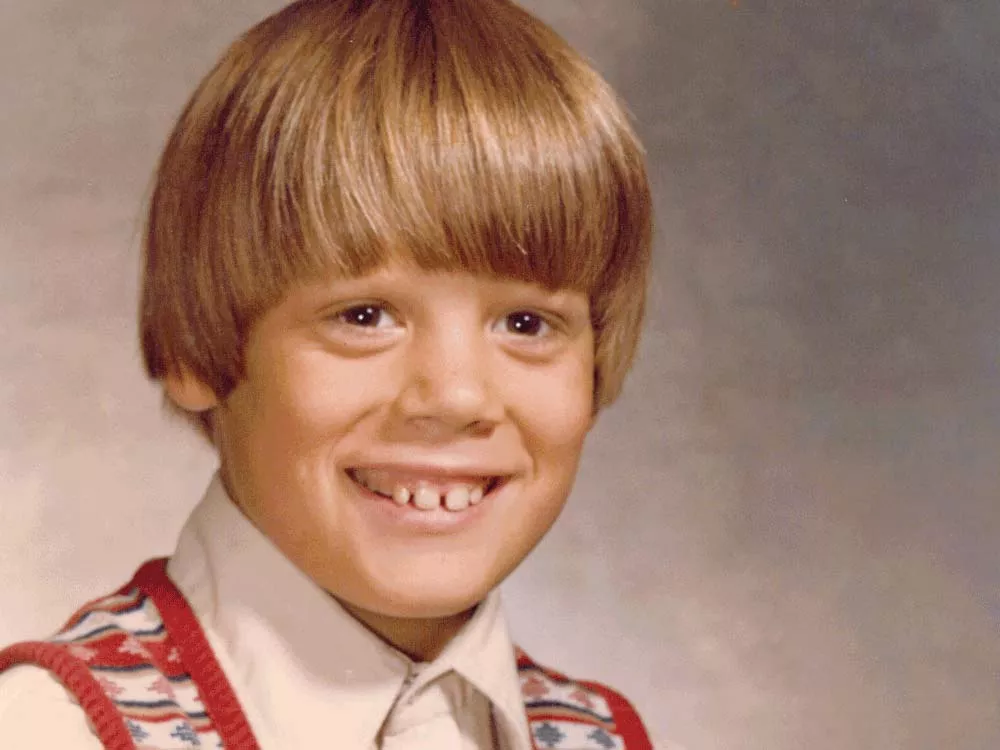

Al Hadlock as a boy, growing up in Spokane Valley

Hadlock in his University High School football uniform.

Hadlock on his wedding day

“At the time [my mom] had three jobs, and she never missed a wrestling match. Never missed a football game,” he says.

Hadlock realized his athleticism in middle school. He was a competitive kid, and he liked the regimen that being an athlete required. Discipline. Routine. Commitment.

“I was really into sports. So into sports [that] I didn’t drink in high school. I didn’t eat red meat,” Hadlock says.

Hadlock says he was a “junior phenom” going into University High School — where he continued to distinguish himself on the wrestling and football teams.

“He was a good kid,” says Don Ressa, who has coached football at U-High since the late ’80s. “He was a hard-nosed, raw-boned, tough athlete who was just a good football player for us. And very competitive.”

In 1987, after he graduated from U-High, Hadlock joined the wrestling team at Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon, and later jumped to Washington State University. At WSU, he dropped athletics and “learned about alcohol.” After his GPA dropped to below 1.0, Hadlock says he was “invited to leave.”

“I loved it. I’m glad I went through it, but it was a waste of a year and a half of my life,” he says.

Hadlock moved home to Spokane and started working as a bouncer at Swackhammer’s, a dance club in north Spokane. But without sports, there was a void in his life. Though he was nearly 22, he enrolled at Whitworth College and played a season of football there.

But Hadlock knew he wasn’t going to play professionally, and he needed to figure out a plan for his future. For a while, he attended Spokane Community College’s Cooperative Education Program with the Spokane Police Department. He also thought about becoming a high school teacher.

“When he didn’t have the regimented life, it was like he just was lost,” his mother says.

One day, a TV commercial grabbed his attention.

“I saw a commercial with these guys in these black berets,” he says. “So ... I call my brother [who was in the military] and asked, ‘Who are these Army Ranger guys?’ “I knew right away — those were the guys I wanted to associate with.”

“Cheer Up, Ranger”

Today, Hadlock wears his military service on his arms. “2 nd RANGER BN,” in black ink, runs vertically down the bone of his left forearm; the Army Ranger motto, “SUA SPONTE” — Latin for “of their own accord” — runs down the right arm.

Rangers are an elite group. “They have to be airborne-qualified. They go in and handle special missions,” Sgt. William Kendall, an Army recruiter, says. “A Ranger doesn’t have time to look up information in a manual on the battlefield. It’s stuff you’ve gotta know.”

The strict physical and mental requirements of the Rangers appealed to Hadlock. He watched as the trainees beside him dropped out one by one.

“Selection was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” he says. “Standing up on that stage at the end with 38 or 39 other guys, out of so many that started. I knew so many guys that would have been excellent Rangers.”

The following years would be the proudest in Hadlock’s life, as he completed several tours of duty overseas.

“The military is the one thing that I really did good in my life,” he says today. “I loved the lifestyle. Special Operations is like the varsity football team. And you train for it everyday — you kick down doors and shoot targets in the face thinking someday this will come around.”

Though the late ’90s weren’t known for large-scale wars, Hadlock says he saw no shortage of special missions. Still, he’s reluctant to share details.

“For me, to talk about it makes me feel more ashamed of the things I did, because so much more was expected of you in the Ranger Battalion,” he says. “We were a hard-fighting, hard-drinking group of guys, but there were always standards.”

His mother remains proud of his service and recounts the time he was injured while parachuting during training into a Panamanian rainforest. A large thorn pierced his hand. Another time, she says, he was dropped too low to the ground. “We just always thought he’d be OK,” she says. “He’s always been strong.”

For most of his career, Hadlock was stationed at Fort Lewis near Tacoma and it was there, on his first day, that he met his future wife, April. The two would marry — Hadlock in his uniform and beret — on July 4, 1997.

Less than two years later, Hadlock suffered a career-ending accident during an airborne operation. Today he’s vague on many of the details, because, he says, he’s not sure which ones are classified.

But the accident was severe enough to leave him with a compressed spine, rupturing discs in his back and shattering several others. He had three surgeries to fix the damage, but he didn’t pass evaluation by the Army’s medical board. He was discharged in early 2000.

Hadlock was lost.

His mother, Beth, thought her son would be in the military for life, and she worried when he was discharged. And when Al and April decided to move to the Midwest — to be near her family — she worried even more.

“I feared it would be bad,” she says. “And it was.”

“All About Me”

Hadlock, April and their young daughter, Meryl, moved to Ohio in 1999 and settled into a rental home on Cimmaron Station, a suburban street on the outskirts of Columbus. Hadlock worked in building security, and then for a collections company, before he was recruited into the mortgage business by some friends.

“I really liked it. I did a lot of home refinances. … In a lot of circumstances, I believe I helped people,” he says.

At home, things weren’t going so well. He and April fought often. During one argument, he slapped her and she called the police. The two went on living together, but Hadlock often crashed with friends, and he had a girlfriend on the side. “Life was all about me,” he says.

He remembers the exact night that everything got worse.

He had closed a deal on a mortgage that day, which would yield a commission of upwards of $6,000. To celebrate, his co-workers took him out for drinks at a strip-mall bar near his house. There, Hadlock struck up a conversation with a guy named John.

“I was bullshitting with this guy, sitting at the bar. … People would come up and talk to him and he’d go in the bathroom. And I didn’t realize right away what he did.

“And it turns out he’s a drug dealer,” Hadlock says. “And then [he says], ‘Here’s a little sample’ and that was it.”

Hadlock says he felt like he was on top of the world that night. Success was his. All his: Hadlock wasn’t interested in sharing it with his family.

“I was doing well. But I was a shit — morally. … I think everybody does that at times, where all you care about is you getting to work. ‘Screw everybody else on the road, I gotta get to work.’ That’s kind of how I was living my life. ‘Screw you. It’s all about me.’”

Hadlock got John’s number and called him a few days later to party again. They hit some bars, did some more coke.

“One line of cocaine and I’m gone. I disappear for three days,” he says. “I’m on the phone to my guy and I’m getting an [entire] eight-ball and I’m doing it all that night.”

Getting high became more important than everything — April, Meryl, his job. Hadlock bounced from friends’ couches to drug dealers’ basements. His boss offered to get him help, but he didn’t want it.

“You keep telling yourself, ‘I can clean up, I can get better, I’m just doing this temporarily.’ [But] that would turn into a four- or five-week bender,” he says.

By the time Hadlock switched from snorting to shooting cocaine, he had dropped nearly 100 pounds. His face broke out with acne. After getting a nasal infection from snorting coke, he felt like shooting would be cleaner — and would get him high faster.

His addiction took over his life. He couldn’t do anything when he was high.

“You’re chasing that first amazing feeling. And you never reach it,” he says. “I can’t tell you one really good time I’ve ever had [when I was] high. Because there are no good times. It just seems like they’re good times.”

Hadlock knew he was sinking fast. When he sensed he was on the verge of sleeping on the streets, he went and packed his Ranger beret and uniform into a box. He wanted to give it to his daughter someday. He wanted Meryl to know the kind of man he was, the kind he could be. And he asked his wife to give it to her when she was older.

In the winter of 2005, Hadlock was living in the basement of another friend, Dustin. April was done with him. His boss had let him sleep at the office for a while but finally had to fire him.

Hadlock and Dustin were at a bar one night, and Dustin asked him why he didn’t put his “special skills” from the military to good use. He could easily rob a bank. Maybe some stores.

“I wanted to get high so I was like, ‘Yeah, you’re right, I think I can do it,’” Hadlock says.

After a few more drinks, the two men left the bar. As they were pulling away, Hadlock told Dustin to stop near a gas station. He told him to keep the engine running.

“I come back and get in the car and said, ‘Drive down that alley.’ And he said, ‘What’d you do?’ And I said, ‘I just robbed that place.’” The gas station was good for $170 — which Dustin and Hadlock spent by the end of the night on more cocaine. “I don’t think I had a dollar left in my pocket,” Hadlock says.

The gas station job gave him confidence. But he knew robbing a bank — supported by the government, filled with security cameras — would be a whole different beast.

"I Kept Telling Myself, 'I'll Get it All Back'"

After he robbed the Columbus bank of $1,400 in May 2005, Hadlock ran directly to a Sprint store, where he paid his phone bill, called his drug dealer, bought more cocaine and headed to a nearby hotel — only blocks away from the bank he’d just robbed.

“I spent the rest of the night looking out my window because I could hear the helicopter flying above,” he says.

Feeling the heat, Hadlock went to crash with another friend, Eric Weerstra, who’d also worked in the mortgage business. Weerstra wasn’t an addict, but he liked to party. Hadlock had crashed with him before when he’d been in trouble with April.

“Eric was a drinker. And he always said [he had] used cocaine but never really got high, so I always made the joke that ‘it’s because you didn’t do enough!’” Hadlock says. “So [my dealer] comes over one day and we’re getting high and Eric sticks his head in the room and I said, ‘Hey!’ … And now I look back on it and I feel bad about it because that kind of directly leads to his addiction.”

Weerstra would soon become Hadlock’s partner in robbing more than two dozen videogame stores, tanning salons, restaurants and bookstores. The plan was always the same: Weerstra would scout stores where they could park his red Volkswagen GTI — their getaway car for every robbery. Weerstra would wait in the car while Hadlock went inside.

Hadlock’s routine was the same, too. He’d wear a hat and a jacket and put a broken pellet gun in the front of his pants. Sometimes he’d wear gloves to cover the tattoos on his hands. He’d wait for the store to clear out, ask for a manager, lift up his jacket so they could see the butt of the gun and calmly tell them that they were being robbed.

In several police reports about the pair’s crime spree, customers told authorities they didn’t even know the stores that they were shopping in were being robbed. After Hadlock got the money from the cash registers, he’d calmly walk outside, take off his hat and jacket and get into Weerstra’s car.

“[That calmness] is one of the reasons we flew under the radar for 31 robberies. It wasn’t a six-state manhunt with marshals,” he says “If you’re doing takedown robberies, scaring people to death … you’re making a big dent in the radar.”

Two weeks into their crime spree, Hadlock called April from a payphone.

“I said, ‘Hey, can I talk to Meryl?’ And April goes, ‘Al? Are you OK?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah! Why?’ And she says, ‘There’s two FBI agents here for you today.’ And I was like, ‘Gotta go!’ Click!”

Their formula — Weerstra driving, Hadlock robbing — worked from Columbus to Cincinnati, up into Michigan, down to Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky. Sometimes they’d knock off as many as three stores in one day. They always chose strip malls. And they always went for chain stores. Hadlock told police after he was arrested that he figured a chain store would be able to absorb the loss better than an independently owned store.

And Hadlock found that employees at those stores were less interested in protecting the company’s interests.

Hadlock says police knew right away he was the one who robbed the bank. This digital rendering and sketch were put out to police departments during his crime spree.

During one robbery, Hadlock asked the employee who handed him the cash to wait a few minutes before calling the police.

“I said, ‘Look man, I know you gotta call the police.’ I’m just like, ‘Let me walk out the door.’ And he says, ‘F- — that, man! I’m not calling the police, I got warrants. I’m calling my boss and I’m going home.’

“I’m laughing as I’m walking out the door,” Hadlock says. “He didn’t give a shit. And I hate to say that because I don’t want to minimize the fact that there was a robbery. But it was still funny.”

Later, at a makeup store, Hadlock ran through the same routine. Ask for the manager, stay calm, tell the manager he’s robbing the place.

“I’m robbing the guy and one of the other [employees] walks up and is talking to him, and he’s just real pissy with her,” he says. “And she starts this kind of pissy banter back and forth with him. He just looks at her and says, ‘Can’t you see we’re being f—-ing robbed?’”

“She looks at me and goes, ‘Oh, sorry!’” Hadlock says.

At another store, a clerk asked what would happen if she didn’t give him the money.

“And I said, ‘I’ll turn around and walk out,’” he says. “And she opened up the till.”

On the Lam

Forty days later, Hadlock and Weerstra decided to quit. The two men had committed robberies in five states, stealing between $10,000 to $15,000. But they’d spent it all on drugs. And they were tired. Hadlock says he doesn’t remember sleeping much. Or eating much.

After one robbery, the two men sat in a ’50s diner in Schaumburg, Illinois.

“Eric looks at me and says, ‘We should turn ourselves in.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I’m tired of running.’”

Weerstra decided he would return home to his family in Michigan. And Hadlock would get on a train in Chicago for Spokane.

They agreed to confess to everything but also decided that Weerstra, who would surely be home before Hadlock’s train would arrive in Spokane, should wait to turn himself in for a couple of days.

They robbed one more place — a video store — to get enough money for a train ticket and to fill Weerstra’s gas tank. They parted ways at a Chicago hotel. Hadlock says he knew he’d never see Weerstra again.

“It was kind of a relief,” he admits.

Despite their agreement, Weerstra quickly called police, trying to strike a deal for complete immunity if he turned in his partner. Weerstra was arrested within 15 hours of parting ways with Hadlock.

Police rushed to Hadlock’s hotel, but they just missed him. He was already on a train to Spokane.

Hadlock had called his mother to pick him up from the Spokane train station, but she couldn’t get there. The authorities had closed several city blocks, anticipating his arrival. It was May 16, 2005.

At 1:05 am, as Hadlock stepped off the No. 27 train, he saw police walking down the platform toward him and noticed the helicopter flying above.

“That’s when I knew,” he recalls. “When I got off the train, it was like, ‘Oh, jig’s up.’”

Pointing flashlights and guns at him, a group of police officers approached him, yelling at him to “get on the f—-ing ground.” Hadlock didn’t resist.

“An FBI guy took out my ID. And he said, ‘You’re Alfred Hadlock, right?’ I said ‘Yeah.’ He says, ‘You know why we’re here? And I said, ‘Yeah.”

Being arrested was a relief, Hadlock says. He promised the police that he would confess to everything he’d done. That night he handwrote a list of every place he could remember robbing.

“I said, ‘I just want to tell you everything I did and be done with my punishment. Get on with my life. Whether that’s five years from now or 50 years from now, I just want it to be over.’”

A New Routine

No crime or Ranger mission could prepare Hadlock for the first time he walked out onto the yard at Victorville Federal Correctional Complex, a high-security prison 80 miles from Los Angeles.

With a six-year sentence ahead of him, Hadlock didn’t think he could make it.

“Even though I accepted it, I thought I was going to kill myself,” he says. “I thought I was gonna hang myself.”

But when he realized he might get out in less than six years, Hadlock pledged to do everything he could to make it through. He wanted to change. He wanted to be a better man. And though he knew that he’d never get back everything he used to have — April, Meryl, his life before drugs and crime — he knew he could be a better person.

“I was tired of being an asshole. And I think that you start not being that person when you go to prison. The choices you make there dictate the person you’re gonna be later,” he says.

His time in the military helped Hadlock adjust to the regimen of prison. But it didn’t prepare him for the politics. He quickly found that races don’t intermingle. You don’t let another race eat with you, tattoo on you, smoke a cigarette with you. And you don’t ever let somebody touch you.

“Your first line of defense is you,” he adds. “And if you’re gonna get punked, you gotta blast that guy as hard as you can and keep fighting until the cops get there.”

Hadlock, who had lost some bulk during his drug binge, was gaining weight and muscle again. And when someone tried to mess with him soon after he arrived, he made sure everyone knew he was not a guy to cross.

“You gotta set that standard early,” he says. Hadlock did that by throwing another inmate off a second-story tier.

“He was fine. He separated his shoulder and I think he broke his femur,” he says.

Hadlock did his time by reading. Chinese philosophy. The histories of religion. The Bible. He kept his own tattoo gun and ink — contraband in prison — and received most of his tattoos there. He worked as a GED tutor. He tried to teach one cellmate to read during a three-month lockdown. And he’d keep bags of water in his cell — using them as weights until they’d get confiscated.

For a while, Hadlock got phone calls from April.

“Things were great. She’d say, ‘We love you, we support you. You’re going to get through this. Cheer up, Ranger.’”

The phone calls stopped suddenly, though. One day, April called and told Hadlock that she’d met someone else. That was the last time they would speak.

“Should she have left me? Yeah, absolutely. She should have left me long before she did,” he says. “Would it have made a difference in me? I don’t know.”

Toward the end of his sentence, Hadlock was transferred to a lower-security prison in Lompoc, Calif. There he continued to pursue the Catholic faith he’d developed at Victorville. He attended Mass — even when it was in Spanish.

“The one thing I did in prison that I swore I would never do was I found God. Since I’ve been out, I haven’t lost any of my faith,” he says. “You see a lot of guys that bang that book in prison, then they forget everything they’ve learned. I’ve managed to bring that with me.”

“We Need the Big Guy”

On a recent Saturday, Hadlock was panting as he pushed a large couch across the linoleum floor at the Goodwill Store in downtown Spokane.

“I’m breaking my no-sweating-at-work rule today,” he says.

He’s over 6 feet tall, but standing next to him, he seems closer to 7 feet. He wears his long black hair slicked back and pulled tightly into a bun. He walks with a slight limp — one of the only indications of his military injury.

Kathy Haugland runs the Re-entry Program at Goodwill Industries, which helps ex-cons reintegrate into society. Upon release, felons like Hadlock face a variety of obstacles, and Haugland’s program helps them get housing, jobs and simple things like drivers’ licenses. And with an estimated 13 million felons living in America, she and her colleagues see a lot of ex-cons walk through their doors every day.

Today, Hadlock works in the furniture department of Spokane's downtown Goodwill store. "His compassion is amazing," Goodwill's Bill Noland says.

But Haugland says that Hadlock, who was hired last September to work in the furniture department at the Goodwill retail store, is one of the organization’s most exemplary clients.

“If you were to meet Al and you didn’t talk to him, he is very intimidating-looking. With the tattoos, the ponytail, being a large frame,” she says. “Once you get to know him, he’s the kind of guy that would absolutely lay his life down for you. I wouldn’t even doubt that one little bit.”

Haugland laughs as she talks about Hadlock working in the store.

“Everybody loves him. They say, ‘We need Big Al. We need the guy with the ponytail and tattoos,’” she says. “And the little old ladies love him. They are just all, ‘Oh my goodness, you are so big!’”

Bill Noland, who works at Goodwill with veterans who have been incarcerated, says that Hadlock is different than his other clients.

“I think he stands out in that he said, ‘I’m ready to work,’ and [he] finds ways to make a successful transition to improve himself,” Noland says. “He found employment. He found a stable housing plan. And he set himself up to go back to school. He’s got a very positive mental outlook.

“He said he wanted to reinvent himself.”

Balancing Act

Al Hadlock says the worst nights are the ones when he wakes up thinking he’s still in prison. “It takes me a minute to realize I’m not there anymore,” he says.

But once he’s up, it’s hard for him to stop moving. He doesn’t have a single day off. Every day he wakes up at 5 am, does his ab workout, gets ready for school, heads to the bus stop and catches the bus either to school, work or a number of classes he’s required to complete for his probation. On the bus, he listens to audio books. He goes to the gym every day. And he has his family — his parents, his brother Tony — and a steady girlfriend to see.

And he writes letter after letter to Meryl, whom he hasn’t seen in six years. He’s never gotten a response. He figures that April is just looking out for her daughter and holding all of the letters. But just in case, he photocopies each one. He copies the birthday cards, too. Last week, he sent his 206th letter to Meryl.

He hopes to get a letter back someday.

In the meantime, though, he gets one step closer to having what he wants most: a normal life.

“All the things that my wife wanted that I wouldn’t give her are the things I so crave now,” he says. “Just to work a normal job and be like everybody else. Go out on a Friday night and sit and have coffee with somebody.

“Those relationships that I so destroyed and then lost completely when I went to prison are the things I crave the most now,” he says.

Sometimes, while telling his story, it’s as if Hadlock can’t believe he’s talking about his own life. Those 40 days of crime and drugs are now the defining moments of his 42 years.

“I look at all the good things I’ve done in my life and I weigh them against the bad things,” he says. “And I don’t know if it’ll ever equal out again.

“My cellie asked me one time, ‘Do you think God will forgive you?’ I said I don’t know if he’ll forgive me, but I wonder if he’ll say, ‘Good enough.’”