The sun bakes the concrete roof of the La Quinta hotel in Coeur d'Alene, where 19-year-old maintenance worker LJ Waldvogel is standing, looking down on the Wild Waters water park below. Nostalgia floods past. A half-dozen years ago, this was where he spent his summers. Back then, his agenda was simple.

"Hang around," Waldvogel says. "Chill. Probably sit in the sun for a bit, get a suntan."

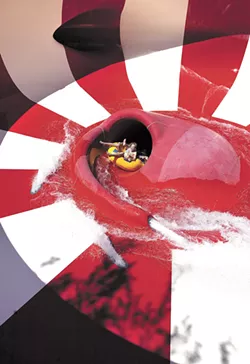

From here on the roof, you can see the entrance to the "Drop Off" slide he loved, the one that ended in a sudden, stomach-yanking dive. It's been six years since anyone has taken that plunge.

If the drivers zooming past on I-90 and U.S. 95 look closely, they can see a for-sale sign, a readerboard shedding letters and chipped paint on the "FLOAT THE LAZY RIVER" lettering.

The slides have become blue-bleached bones strewn across an ancient ruin. The water that remains has turned fetid and black — mixed with soil and sludge — languishing in the slides' plateaus. Weeds peek out of the swamp at the slides' exit. Stripped of covering, umbrellas perch like giant spiders across the property. The padlocks, wire and chain-link fences haven't stopped graffiti tags from sprawling across the pumphouse.

"Silverwood's OK. I just wish they could reopen this place," Waldvogel says. "It brings back good memories."

But reopening is unlikely — not just because of why Wild Waters shut down, but because of what happened afterward.

Flood of competition

In 1982, a man-made mountain 70 feet high rose up in the middle of Coeur d'Alene. Then-Chamber of Commerce president Sandy Emerson predicted the opening of Wild Waters could mean the difference between Coeur d'Alene as an "overnight tourist town" and Coeur d'Alene as just a "gas and lunch stop."

The developer, a Canadian company, hoped its $1.5 million water park would attract 800 people a day. Two months after it opened, it was attracting nearly twice that.

Splash Down opened a few years later in Spokane Valley, but Wild Waters remained the king.

Splash Down co-owner Geoff Kellogg says his wife grew up well aware of that. "She always said that Wild Waters was bigger and better," Kellogg says. "[But] her mom wouldn't take her all the way over there. It was either Splash Down or nothing."

For years, the two parks slid neatly into their roles: Splash Down was cheap and simple. Wild Waters was pricier, but more expansive and thrilling, with slides like the pitch-dark, strobe-lit "Black Hole," launched in 1996.

But then came "Boulder Beach." In 2003, the Silverwood Theme Park behemoth dipped its toes into the water-park business.

"It took off like gangbusters," says Mark Robitaille, marketing director for Silverwood. "I believe that we were in a different level than Wild Waters."

Wild Waters, of course, knew the threat was coming. "We beefed up for it," says Sherry Henry, general manager of Wild Waters back in 2003. "We knew we were going to have to do something to keep people coming back." They added improvements, like a water-throwing game called "Water Wars."

But in the water-slide arms race, Silverwood always wins. A year later, it had added speed slides. In 2007, Wild Waters began a $4 million expansion project, starting with a "Lazy River" attraction. Silverwood upped the ante, doubling the size of Boulder Beach in the same year.

Wild Waters was stuck in the middle, both geographically and financially. Want something cheap and close to Spokane? Go to Splash Down. Want the premium experience? Drive a bit further, pay a bit more, and get roller coasters and Tilt-a-Whirls thrown in for good measure.

A water park is a finicky business: You have maybe three summer months to make enough to pay for 100 employees and a yearlong lease. Your fortunes depend on the skies. Just as warm or dry days can devastate a ski resort, cold or wet days can devastate a water park.

No wonder the latest trend, according to Aleatha Ezra at the World Waterpark Association, is "the indoor water park affiliated with a resort or a hotel." In 2005, the Triple Play Family Fun Park built a small indoor water park at a Holiday Inn Express just 4 miles away from Wild Waters. In 2008, Silver Mountain Resort built a much larger indoor water park attached to the ski resort. These parks are far pricier to build, but are less vulnerable to meteorological whims.

Wild Waters was being hammered from all sides by competitors. In 2010, it didn't open at all.

Its website explained that "refurbishing of slides and new renovations and construction projects that are needed. LOOK FOR THE NEW & IMPROVED PARK the SUMMER OF 2011." The next year, the website disappeared entirely. Without explanation, Wild Waters never opened again.

Family feud

Behind the scenes, the problems at Wild Waters went far deeper than cloudy days and new competitors.

Wild Waters' owners had never intended to own a water park. It was the Bank of Idaho's decision, managing Coeur d'Alene businessman's James E. Lavin's trust, to lease the property to a Canadian company to build a water park.

The hope was that Wild Waters would generate revenue for James Lavin's heirs. Instead, it became a millstone around their necks. In 2003, control of Wild Waters fell directly to the Lavin family.

Former co-trustee Stacey Lavin and other family members did not return repeated requests for comment, but legal documents outline chaos and bitterness as Wild Waters helped to drive a wedge between the Lavins.

To the dismay of much of his family, Stacey repeatedly issued loans, with unspecified repayment terms, to improve Wild Waters. Within seven years, $1.1 million had been loaned out to the water park, and the park was barely able to pay anything back.

No one could accuse Stacey of not caring deeply about Wild Waters.

"It's always a crisis with Stacey," an email from then co-trustee Joe Lavin lamented in 2006. "He gives me a 15-minute discussion on BIG ideas which include investing 400,000 dollars into waterpark rides."

Stacey designed the Lazy River personally. He hired his own construction company to build the attraction — opening himself to accusations in legal filings of "self-dealing and misappropriation." The project was an utter debacle, court documents say, "plagued by cost-overruns, permit delays, and weather-related construction delays." Simultaneously, weather closed the water-park business for "numerous days."

The attraction was supposed to increase Wild Waters' flagging revenue. But a subsequent financial statement was blunt: "These increases did not materialize." By 2009, Wild Waters' property taxes weren't even being paid. The park fell into disrepair.

That's not to say that some didn't see an opportunity in the property: In 2011, two copper thieves, armed with a bolt cutter, a hacksaw and an orange pipe wrench, sliced through the outer fencing, broke into the pumphouse and began sawing off and ripping off copper piping, destroying pumps, smashing windows and tearing out wires.

Wild Waters' insurance company rubbed salt in the wound: The fine print of the insurance policy, it explained, didn't cover vacant properties. Wild Waters became locked in a two-year legal battle, but the insurance company exited victorious; insurance wouldn't pay for the damage left by the vandals. At the same time, an even uglier two-year legal fight was waged between the Lavins over control and terms of the trust.

Amid the chaos, at least one water-park operator considered restarting Wild Waters.

"It's a great location for a water park," says Burke Bordner, owner of Slidewaters in Chelan, Wash. "You'd need some new 'wow factor' ride that [isn't] at either of the other two [nearby outdoor] water parks."

But the vandals had done their damage. Purchasing it wasn't practical.

"People snuck in there, and disconnected every single pump and opened every single panel," Bordner says. "You've got a park that basically needs to be rewired with every single part."

Instead, area water parks picked over the ruins, searching for great deals on usable equipment. The big slides hadn't been maintained. But Slidewaters bought a giant red tipping bucket. And Splash Down, much improved since Wild Waters' heyday, bought play equipment and kiddie slides from the defunct park.

"We got six slides from them," Kellogg says.

The question remains: What happens to Wild Waters' ruins? After all, the property is for sale. If not a water park, the man-made mountain would have to be flattened, Kellogg says — not a cheap undertaking. But the central location has real potential.

"It could be a Home Depot. It could be a Larry Miller car dealer," Kellogg says. "Certainly the land value is more than what a water park would bring." ♦