It felt like the whole town was there.

More than 80 people packed the room, and those who couldn't find space spilled out to listen from the hallway. It was a sizable turnout for a weeknight city council meeting anywhere — especially so in Chewelah, a town of 2,400 about an hour north of Spokane.

There were only two topics on the agenda. A presentation on the first item — something about shoreline regulations — was delayed by technical issues. The mayor had to step in and fiddle awkwardly with the TV.

Everyone was there for the second item: a public forum on two new 16-bed facilities — one for patients living with dementia, the other for people with intensive behavioral health needs stemming from things like developmental disorders or incidents involving traumatic brain injuries. The project is funded by a $1.6 million grant from the state Department of Commerce, part of a larger project to shift away from big mental health facilities like the troubled state hospitals, and put resources toward smaller, community-based ones.

At last week's meeting, residents made their opinion clear: The city needs to do everything in its power to stop the facility.

"We're not against mental health or anything like that," said Joseph Reddick, a Chewelah resident, at the Wednesday public forum. "We're against having it in our backyard."

John May, a Chewelah resident since 1942, put it bluntly to council members: "The behavioral modification folks are there because they're jerks."

Council members tried to explain that, in many ways, their hands are tied. They'd already passed an emergency moratorium in February to delay the project, which is set to expire this summer. But property owners have land rights, and the state government has jurisdiction. Several residents asked if the city could just "screw the law."

Michael Waters, the city attorney, stepped in. He explained that while he sympathizes with the sentiment, ignoring state law would be a very bad idea.

"The city could be on the hook for millions and millions and millions of dollars it doesn't have, directly bankrupting the city and destroying everything in the process," Waters said. "We're gonna have to figure out a way to do this within the law."

If he could go back in time and do it all over again, Kenton Cox isn't sure he'd accept the grant.

"We don't like controversy," Cox says. "It's not fun to be hated by a few or be a target of animus, but this is the position we're in right now."

In February 2020, Cox bought Quail Hollow, an assisted living facility with 16 beds in Chewelah. It was a business decision, Cox says, but the desire to make a difference and improve the lives of vulnerable people also played a role.

The type of patients admitted to assisted living facilities varies quite a bit. The previous owners of Quail Hollow had mainly catered to more mild cases — "the traditional grandpa and grandma peacefully rocking the rocking chair," Cox says.

After taking over, Cox says, they also started admitting patients who needed a bit of extra help, like younger people who can't live on their own because of traumatic brain injuries.

In early 2020, a staff member noticed that the Department of Commerce was offering millions of dollars for care facilities across the state. Cox saw an opportunity to follow up on the previous owner's plans to one day expand Quail Hollow and figured the grant could help cover construction costs. He says he didn't even consider the possibility of community pushback.

The intensive behavioral health wing funded by the grant would be for people who no longer benefit from treatment at institutions like the Western and Eastern State Hospitals, but who still require support. The patients might need a bit of extra care, but overall, Cox says, they wouldn't be that different from the people Quail Hollow currently serves as an assisted living facility.

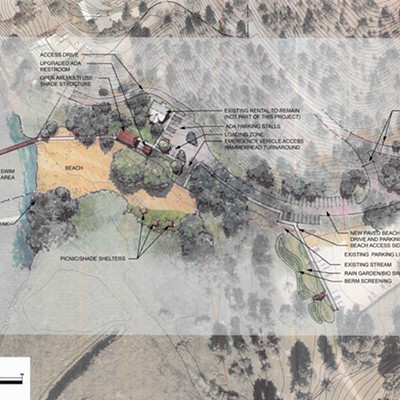

Commerce approved the grant in 2020. The pandemic delayed the planning process but by summer 2022, Cox says, the city had approved a construction permit. He started building. It seemed to be going well.

Then everything changed this winter.

"We were blindsided," Cox says.

The Chewelah facility is part of a larger five-year plan launched by Gov. Jay Inslee in 2018 to "reimagine" the state's health care system. Fewer big, state-run institutions like the troubled state hospitals, more smaller ones like Quail Hollow.

"Large institutions were popular in 1918, but in 2018 we know smaller hospitals closer to home are far more effective," Inslee said at the time.

In an effort to build more of those smaller, close-to-home hospitals, Commerce has awarded more than $160 million to 59 projects across the state. The grants are open to providers with expertise and the ability to expand, and focus on medically underserved areas like Chewelah, according to Penny Thomas, a Commerce spokesperson.

In Spokane, the state put $1.8 million toward the construction of Greenacres Residential Care in the Valley, and $1.7 million to Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center for behavioral and educational skills training. Spokane County also received $1.9 million for the construction of the 32-bed Mental Health Crisis Stabilization Facility, which local leaders debuted with a ribbon-cutting event in 2021.

While other Commerce-funded projects, like Catholic Charities' Catalyst Project homeless shelter in west Spokane, have drawn significant neighborhood pushback, the mental health projects in Spokane have seen little resistance or negative publicity.

But that hasn't been the case in other parts of the state.

In Clark County, a planned behavioral health facility met with opposition from neighbors concerned about the building's proximity to schools. Neighbors concerned about safety and being left out of the planning process have also organized to protest an involuntary treatment center in Stanwood.

And then there's Chewelah.

Abbie Hawvermale, a nurse at Quail Hollow, thinks the backlash started in December after neighbors noticed the new buildings going up. Residents circulated a petition urging leaders to stop the facility. The city quickly stepped in and passed the emergency moratorium in early February.

"It's a little surprising that the town's in an uproar," she says.

Cox says he's been transparent and communicative with city officials throughout the process. But Mayor Greg McCunn says that the city wasn't fully informed about the full scope of what "intensive behavioral health treatment" actually meant until this January.

Now that the city has a clearer picture of what type of patients the facility would serve, McCunn says the city needs to take a step back and evaluate whether or not they have the resources to actually support it.

"That's the position the state agencies have put us in," McCunn says.

McCunn points to documents from the Washington State Health Care Authority that say people should only be admitted to intensive behavioral health facilities if they "require more intensive services due to dangerous or intrusive behaviors, complex medication needs, a history of unsuccessful residential placements, a history of hospitalizations, or a history of violent or felony offenses."

It's shocking, McCunn says.

Cox understands why people are alarmed. But he argues that the violent and criminal behaviors described in the document are outlier cases that don't represent a majority of the patients the new facility would admit.

The city is letting Cox move forward with construction, but the moratorium stops him from getting the occupancy permit he'll need to actually operate the facility once it's finished. If the city finds a permanent way to stop the building from being used as a behavioral health facility, the Commerce funding Cox was counting on to cover the construction costs will go away — leaving him on the hook for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Cox tried to answer the community's concerns at a town hall event in February. He says he was met with valid questions and criticism, but also personal attacks, misinformation and vitriol. With that in mind, he decided not to go to last week's meeting.

"It almost sounds like the town thinks we're bringing in felons and rapists," says Hawvermale, the Quail Hollow nurse. "That's not what we're doing here."

Many residents are concerned about Quail Hollow's proximity to local schools. The building is just a few blocks from the local high school and elementary school.

Over the past year, there have been two incidents involving Quail Hollow residents leaving the facility and wandering into the neighborhood, prompting alarmed neighbors to call the police.

McCunn argues that the town is far too small to handle this type of facility. The five-person police department is already stretched thin, he says, how are they supposed to handle an influx of unstable people in the community?

Since the incidents, Cox says his staff have been on high alert and strengthened their policy of not allowing residents to go out into the community without staff accompaniment. He's also looking into adding fences and cameras once the facility is finished.

Cox doesn't want this to get ugly. He says many of the city's concerns have been reasonable, and that he wants to find a way for everyone to just get along. But he's not backing down either. He says he's hired an attorney to defend his rights as the landowner if it comes down to it.

At last week's City Council meeting, city officials asked the residents to help brainstorm ideas for an ordinance that would stop the facility or otherwise restrict its use. Perhaps something saying it can't be within 500 feet of a school?

"How about 5 miles?" someone yelled, prompting applause. ♦