Do you remember how exciting it was in high school when you got to leave class early for a doctor's appointment? That moment of relief as you spent an hour or two away from the classroom felt magical, but if you asked your parents, they might remember it differently.

They'd probably recall the frustrating work it took to rearrange their entire day to take their kid across town for a regular checkup that couldn't possibly be scheduled at a more inconvenient time.

In response to that lack of easily accessible student health care, Spokane Public Schools (SPS) has partnered with CHAS Health to build health centers inside three of the district's high schools: Rogers, Shadle Park and North Central.

"A huge component of excellent, equitable health care is access," said Rebecca Doughty, the executive director of School Support Services for SPS, in a June 2024 announcement about expanding the clinic offerings. "Delivering care to people where they are at — in this case, students — helps address this issue."

Another component of that equitable health care access included building those clinics in schools with high rates of low-income students. More than half of students at the three schools — 54% at Shadle Park, 63% at North Central and 79% at Rogers — are considered low-income, according to the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Districtwide, about 62% of SPS' 29,444 students are considered low-income.

Rogers High School's clinic opened in fall 2019 as a pilot program. While it faltered in its infancy due to pandemic restrictions preventing students from attending school in-person, it's since seen positive results. In the last 12 months alone, Rogers' clinic has served more than 650 patients through nearly 2,000 visits.

Students are allowed to visit the school clinics without a parent or guardian present, but they must provide explicit parental consent before any care can be provided. Providers often connect with students' families to talk about their health and to provide resources on preventative health such as nutrition and exercise.

"Parents really appreciate being able to have a close connection with their provider," says Tamitha Shockley French, CHAS Health vice president of communications and public policy. "They're not having to leave work to go pick up their kid and take them across town — nobody misses school or work, so I think that's a thing parents really love."

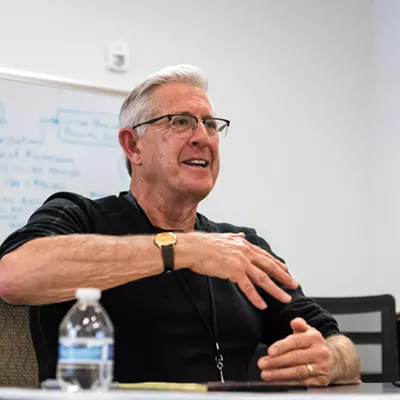

The clinics inside North Central and Shadle Park, which both opened in May 2024, have already proved invaluable to some students, says Jeff Hayward, one of CHAS Health's lead physician assistants. For example, Hayward saw a student who'd been struggling with poor vision and was able to get them prescription lenses.

"This was like the week before school was done," he says. "That's almost the whole school year he was struggling to even read the board, and we got him glasses in just a few weeks."

Born and raised in Spokane, Hayward always knew he wanted to make a difference for his community. So, when he attended Western Washington University in 2001, he decided to pursue a degree in psychology. A few years after graduating, he took a job as a mental health case manager at Frontier Behavioral Health.

Hayward loved his job providing mental health care, but there was no chance for advancement with only his bachelor's degree. So in 2013, after about five years at Frontier, Hayward enrolled in the University of Washington's physician assistant master's degree program. He completed the program in 2015 and returned to Spokane to work at CHAS Health. After the Rogers High clinic opened in 2019, Hayward was named lead physician assistant there.

"I feel like I'm giving back in the same way that I received from my community," he says.

Hayward's work in the health centers is mainly focused on a generalized regimen of care, but his background in mental health has proved vital while working with students.

"As far as really helping people, I don't think I'll ever do anything better for an individual person than I used to in mental health," he explains. "But, it feels like in family medicine I can do a greater spectrum of care for people where I can address multiple aspects of their health."

As he bounces between the three high schools, his work includes both in-person and telehealth visits. And unlike school nurses who deal with in-the-moment care, such as stomachaches and administering medication, Hayward can address patient health, including making diagnoses and prescribing medications. Additionally, Hayward's team can provide school-required medical services like annual physical examinations required for sports participation and up-to-date vaccines. The clinics are open year round, from 7:30 am to 5 pm Monday through Friday.

"This is the age when you connect with people... and help them build a pathway where they're stable for the rest of their life," he says. "I think to be able to intervene in this way has such a profound effect on them, and that's what I love."

Each new clinic cost about $300,000 to install. About half of the funding came from Spokane city government, and the rest came from the school district's annual capital project funding, which includes leftover funds from the district's bonds.

Hayward says SPS and CHAS Health plan to open more health centers as the need arises.

"Wherever there's a need, we want to be there," Hayward says, "and what else is better for them than to meet their needs right in the place where they're at during most of the day?" ♦