As many Americans were gearing up to enjoy some extra time off over Labor Day weekend, U.S. Democratic Sen. Bernie Sanders and his team were gearing up to fight for causes close to the holiday's labor-rights origins.

All summer, Sanders has railed against big corporations for their labor practices, with social media posts and videos aimed at exposing poor conditions and wages for workers at the likes of Disney, Walmart, McDonald's and other giants.

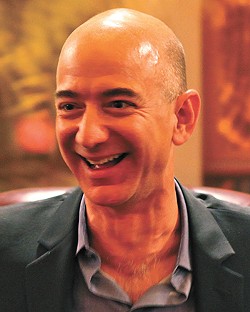

But perhaps more than the others, Amazon has received his ire. In addition to calling out the company for not paying any federal income tax in 2017, Sanders repeatedly criticized founder and CEO Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world, because many of his employees rely on public assistance such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly called food stamps).

"His wealth increases by another $260 million every single day. You got that? You might think that he had enough money to pay his workers a decent wage," Sanders says in a video posted on Aug. 29. "And yet that is not the case. Bezos continues to pay many thousands of his Amazon employees wages that are so low that they are forced to depend upon public assistance."

So Sanders planned to introduce legislation after Labor Day that would tax large employers dollar-for-dollar for the public assistance used by their employees. While incentivizing companies to pay their employees higher wages, the measure would shift the burden from taxpayers back to the companies, he said.

Amazon quickly hit back against the attacks, refuting Sanders' claims about public assistance and encouraging its fulfillment center employees to tweet positive things (in exchange for gift cards) about their experiences working at the company. Taking into account cash, stock and incentive bonuses, the average U.S. hourly wage for a full-time associate in a fulfillment center is more than $15 an hour, before overtime or benefits, the company wrote in a statement last week.

"Senator Sanders continues to spread misleading statements about pay and benefits," Amazon wrote on its blog Day One. "Senator Sanders' references to SNAP, which hasn't been called 'food stamps' for several years, are also misleading because they include people who only worked for Amazon for a short period of time and/or chose to work part-time — both of these groups would almost certainly qualify for SNAP."

Wages for the new fulfillment center in Spokane haven't been set yet, but will be based on similar jobs in the region to be competitive, says Lauren Lynch, an Amazon spokeswoman for Washington state projects. Full-time warehouse associates get medical, dental and vision benefits from the day they start, and they're the same benefits employees like Lynch get, she says.

It's less clear if that applies to temporary workers. While Amazon plans to bring more than 1,500 full-time jobs to the Spokane fulfillment center, there will also be a need to potentially double that during the peak holiday shipping season. Lynch didn't answer whether those temporary workers would qualify for the same benefits, but said temporary employees only account for a small percentage of the Amazon workforce on average.

"Throughout the year on average, nearly 90 percent of associates across the company's U.S. fulfillment network are regular employees who receive full benefits," Lynch writes in an email. "Temporary associates receive the same base wage as our permanent associates at the same job level."

But wages and benefits weren't necessarily the main concern for warehouse laborers. In video interviews posted on Sanders' Facebook page, workers at several levels of Amazon described highly surveilled work environments, where bathroom breaks are closely monitored and there's extreme pressure to meet goals that may be unattainable.

"There was a point where I would find myself crying on my shift," Seth King, who served eight years in the Navy, says in a July video about his experiences in a fulfillment center. "I really felt like I just didn't want to be alive anymore if that was the future that I had to look forward to."

King describes not being allowed to sit or talk to coworkers during backbreaking 10-hour shifts that require workers to be on their feet, walking miles a day through the massive warehouse where they scan, store, pick and pack items. The walk through the large building ate into down time, and if bathroom trips were taken outside of two 15 minute breaks or a 30-minute lunch, King says a manager would approach him and ask why he wasn't being productive.

James Bloodworth describes similar pressures in his book Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low-Wage Britain (which sells for $10 for Kindle on amazon.com). One time at the Amazon fulfillment center where he worked in Britain, Bloodworth says in TV interviews, he found a bottle of urine, likely a sign of the pressure not to be off the warehouse floor for too long. Bloodworth also says he got in trouble for taking a sick day.

But Amazon refutes those characterizations, saying workers can go to the bathroom whenever they want, they're not monitored every second they're working and they are not penalized for taking sick time.

"Amazon ensures all of its associates have easy access to toilet facilities which are just a short walk from where they are working," Lynch writes. "We do not monitor toilet breaks."

Employees aren't tracked minute by minute, Lynch writes, but like other companies, there are performance expectations for all employees, with productivity targets "based on previous performance levels achieved by our workforce."

Employees also receive a "block of unpaid time off to account for running late and they can use that time like a checking account, deducting when necessary for time out of work," Lynch writes. The unpaid time is on top of paid vacation and paid sick days offered to workers.

"We want our employees to succeed in their jobs," Lynch writes, "and managers actively work with employees to ensure we're providing a fun, safe place to work." ♦