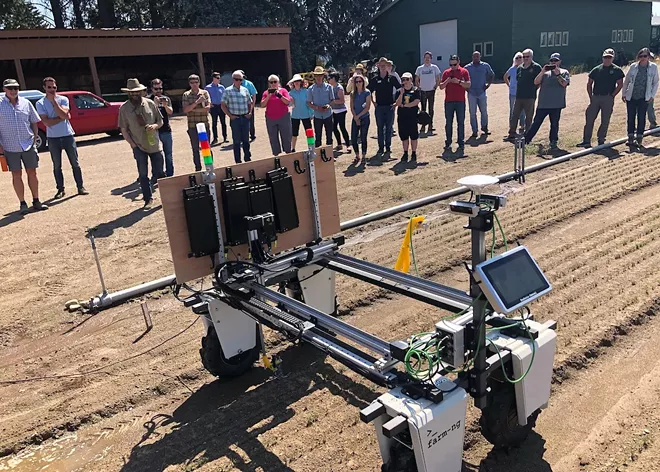

A robot the size and shape of a square kitchen table wheels over a row of seedlings. It scans the ground with camera "eyes," then stops. A small probe lowers from the middle of the robot, homes in on its target, then drops into the earth to pierce a tiny plant. It shocks the plant with an electric current so hot, the plant's cells break down immediately.

Robot: one. Pigweed: zero.

This weed-killing robot was built by the University of Idaho's robotics team for the U.S. Forest Service. It's modern tech's answer to what would otherwise be hours of exhausting, expensive physical labor.

The Forest Service grows millions of trees each year in its Coeur d'Alene nursery. Because the nursery is inside city limits, it's not allowed to use the powerful pesticide fumigants that are standard across the industry to kill weeds. Instead, it spends about $100,000 a year paying workers to weed — that is, if the agency can find people to do it.

Last year, associate research professor John Shovic, postdoctoral researcher Mary Everett and doctoral student Garrett Wells formed a team of engineers from U of I's Center for Intelligent Industrial Robotics in Coeur d'Alene to build an automated weeding robot with a $139,000 grant from the United States Department of Agriculture. The project could save the Forest Service hundreds of thousands of dollars and alleviate staffing issues for years to come.

The team named their venture Project Evergreen. This spring, Evergreen the robot has been out in the fields doing what it does best — frying the living sh*t out of anything that's not a tree.

The team plans to keep upgrading Evergreen — swapping battery packs for solar panels, improving the programmed intelligence, and building it some friends — but right now, the robot is already a big step toward reforesting public lands with millions of healthy saplings.

Two years ago, the U.S. Forest Service faced a backlog of at least 4 million acres of public land that needed to be reforested.

The REPLANT Act passed as part of the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021, a sweeping $1.2 trillion investment in American projects. The act lifted the cap on reforestation spending to get more trees in the ground faster. There are six Forest Service nurseries across the U.S., including the one in Coeur d'Alene, that grow the young trees for three years before they're transplanted elsewhere. There's more pressure than ever to grow more trees as high volume wildfires rage across the West.

The North Idaho nursery has 130 acres of seed beds that look fuzzy thanks to millions of baby trees — and other unwanted plants, too. Even though it's a huge amount of labor to weed through all those beds, the basic concept is plenty simple for a robot, Shovic says.

"This robot is a very sophisticated robot, but what we are weeding is much simpler than your garden from a robot's perspective," he says. "Everything's in the same row, it's the same width, and you've basically got a monoculture of trees."

The robot's target victim is anything that's not a tree. The team only needed to give the robot the artificial intelligence to differentiate "tree" from "not tree" (which most gardeners would agree is much easier than teaching a novice the difference between desirable pea shoots, beet tops, or arugula sprouts, and undesirable chickweed or purslane).

Students taught the robot with their own, very human, intelligence — and perseverance. They took thousands of pictures of tiny plants on the ground, marked each one as either "tree" or "not tree," and fed that information into the robot's software.

Now, the robot can identify "not trees" more than 80% of the time. The team hopes to improve the accuracy in years to come.

The next trick was to figure out how to kill the "not tree." Chemicals were prohibited. Digging could damage the roots of nearby trees. One student suggested using a blowtorch to burn weeds.

"I said, 'Listen, the Forest Service is sponsoring this. Smokey Bear is sponsoring this. We're not going to do it with fire,'" Shovic says.

But there are no bad ideas during a brainstorm. The blowtorch idea spawned the winning solution that's a touch more refined: an electric current. When it identifies a "not tree," the robot lowers a small metal rod a few millimeters into the ground to zap that weed with 3,500 volts — which is nothing compared to the 35,000 volts that dragging your socks across carpet can create, but enough to decimate the plant without harming any trees around it.

Evergreen can cover about half an acre in an eight- to 10-hour shift before it needs to roll back to its charging station and juice up for the next day. It's going through final testing stages this spring as the team's first contract with the Forest Service comes to an end.

Shovic hopes to procure more contracts in the future, since the Forest Service will need a fleet of at least four to five robots to manage their North Idaho acres.

"Someday, we may build as many as 40 of these to cover all six of the nurseries," Shovic says. "But that's sometime in the future." ♦