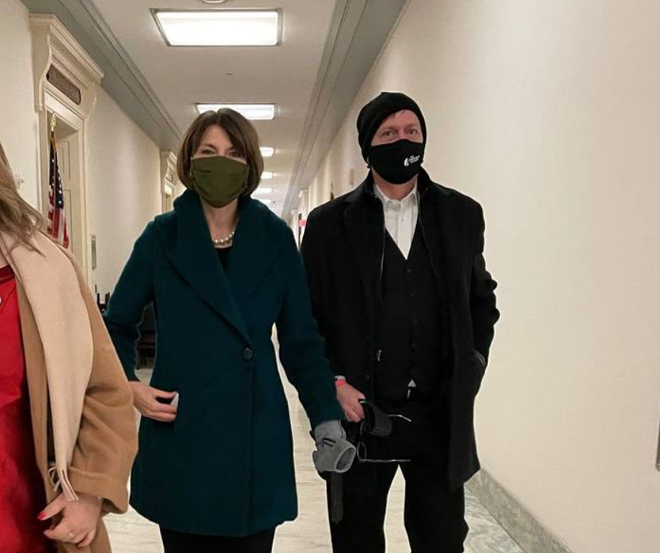

Photo from Rep. Jenniffer González's Twitter feed

Spokesman-Review Editor-in-Chief Rob Curley sporting a Spokesman-Review-branded mask attends the inauguration as the guest of Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Washington.

A lot has happened since Jan. 5 when Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers told the Spokesman-Review she planned to object to the Electoral College results showing Joe Biden had been elected president. A mob of Donald Trump supporters attacked the Capitol. McMorris Rodgers reversed her vote on the Electoral College. Trump was impeached, again.

The local media wanted more than just press releases. They wanted answers. The Spokesman-Review, the Inlander, KXLY and the Seattle Times all reached out with interview requests for McMorris Rodgers, but struggled to get access. The Inlander didn't get any response to multiple phone calls and emails.

"She’s frustrating," Spokesman-Review Managing Editor Joe Palmquist says. "We’ve expressed that. It’s very hard for us to accept the fact that she doesn’t want to get back to us... Sometimes all we get are these statements. They’re the bane of our existence. We hate them!"

"[She] thought it would be a unique opportunity for somebody from Spokane to witness this history," Palmquist says. "I don’t know that there's a media organization that would turn something like this down."

Yet those same media organizations know that such an invitation can raise a host of ethical issues.

"This whole conversation was initiated by her," Palmquist says. "Like any reporter or any editor, he’s very suspicious when people reach out like this."

Palmquist says Curley called him and they chatted about it and wanted to make sure there wasn't an ulterior motive to the invitation. McMorris Rodgers, Palmquist says, assured Curley there weren't any strings attached.

McMorris Rodgers, Palmquist says, didn't pay for any part of Curley's trip.

Yet those same media organizations know that such an invitation can raise a host of ethical issues.

"This whole conversation was initiated by her," Palmquist says. "Like any reporter or any editor, he’s very suspicious when people reach out like this."

Palmquist says Curley called him and they chatted about it and wanted to make sure there wasn't an ulterior motive to the invitation. McMorris Rodgers, Palmquist says, assured Curley there weren't any strings attached.

McMorris Rodgers, Palmquist says, didn't pay for any part of Curley's trip.

"We paid for the trip, we paid for the hotel, we paid for the meals," Palmquist says.

While most of the Spokesman-Review's reporting staff were surprised to learn that Curley was McMorris Rodgers' guest, Palmquist says he was in the middle of writing up a statement to send to the staff to assure them that "we're not trading favors at all."

Palmquist says that Curley assured him that their editorial coverage wouldn't be impacted by the trip. He notes that Spokesman columnist Shawn Vestal recently wrote "a really intense column" — it accused McMorris Rodgers of selling her soul, called her a "mediocre representative, unimpressive by every yardstick" and concluded that "she bid farewell forever to the tiny, final remnants of her good name" — and said that that sort of writing would continue.

And yet ethical questions remained. Like, was McMorris Rodgers using Curley as a way to showcase "civility" to the press without actually subjecting herself to tough questions?

By email, the Inlander asked Curley if he spoke to McMorris Rodgers about any of her recent votes or her unwillingness to grant recent interview requests to the Spokesman-Review.

While Curley plans to write a column on the experience, Palmquist says, it's going to be more of a "fly on the wall" narrative as a sidebar to their main story.

On Twitter, however, reporters across the region reacted with bafflement to Curley's attendance.

"Unless it's been entirely rewritten since I left the Spokesman, I am struggling to understand how this would not be a blatant violation of the paper's written ethics policy for journalists," wrote former Spokesman-Review reporter Rachel Alexander. "I am also struggling to understand why the paper's editor would be the best person to send rather than the talented political reporters on staff."

Asked by the Inlander why the newspaper didn't send a reporter instead, Palmquist indicated that that wasn't part of the invitation, though he acknowledges that they "could have just said, 'No, [Curley] can’t go, but let our reporter be the plus one,'" Palmquist says. "Unless it's been entirely rewritten since I left the Spokesman, I am struggling to understand how this would not be a blatant violation of the paper's written ethics policy for journalists," wrote former Spokesman-Review reporter Rachel Alexander. "I am also struggling to understand why the paper's editor would be the best person to send rather than the talented political reporters on staff."

Spokesman-Review reporter Orion Donovan-Smith did confirm that he was able to connect with McMorris Rodgers today for a brief phone conversation after the swearing-in ceremony.

Other outlets, however, were not as lucky. When KXLY News Director Melissa Luck reached out with an interview request, she was told that "Cathy doesn't have any media availability this week," she wrote on Twitter.

Like the Inlander, KXLY had peppered McMorris Rodgers' office with interview requests, only to get silence.

Other outlets, however, were not as lucky. When KXLY News Director Melissa Luck reached out with an interview request, she was told that "Cathy doesn't have any media availability this week," she wrote on Twitter.

Like the Inlander, KXLY had peppered McMorris Rodgers' office with interview requests, only to get silence.

"I wrote five emails since 1/6 (including today) asking for an interview," Luck wrote in a Twitter message to the Inlander. "Not a single response until today - confirming Rob [was her guest to the inauguration] and denying my interview."

Last year, the Spokesman sparked waves of outrage, both internally and externally, when the newspaper endorsed Donald Trump for president — a unilateral decision from Publisher Stacey Cowles. A few days later, Curley wrote a column announcing that the paper had decided to end "unsigned editorials" and endorsements.

Last year, the Spokesman sparked waves of outrage, both internally and externally, when the newspaper endorsed Donald Trump for president — a unilateral decision from Publisher Stacey Cowles. A few days later, Curley wrote a column announcing that the paper had decided to end "unsigned editorials" and endorsements.

"Suffice it to say stuff like this made my decision to leave the Spokesman-Review much, much easier," former Spokesman-Review reporter Chad Sokol tweeted today. "Once again this kind of schmoozing undermines the work of my friends (reporters and several fantastic midlevel editors) who strive to hold leaders accountable and at arm's length."

Curley, of course, is not the first editor to draw that kind of scrutiny.

Even legendary Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee was dogged by journalism ethics questions about his close relationship with President John F. Kennedy, including granting Kennedy the right to "keep anything he wanted off the record — at least until 5 years after he left the White House."

"His relationship with Kennedy made it very difficult on his reporters," Palmquist says.