"I do," I said, "every day." And swept my hands over my body.

"No, I mean like a real Indian."

"Done," I said and snapped my fingers still wearing the Dansko boots, jeans and sweater I had come to work in.

"No," she said, a frustrated laugh escaping. "Dress up like Pocahontas for Halloween. Or at least wear a doeskin dress and headband. It would be perfect for you."

"Why can't I dress up like an Indian woman? It's just a costume."

She was a student in my Native Literature course. We were talking about appropriation and she was set on proving that she had a right to dress up in the Pocahottie costume she purchased on Amazon.

"Dressing up and playing Indian is not a harmless activity," I said, reminding her and the other students what we had discussed after reading The Round House by Louise Erdrich. I recited again the statistics of sexual assault on Native women, one in three, and reminded the class that they are more than twice the national average. "A costume based on race or ethnicity extracts the human."

"And if those aren't enough reasons," I continued, "how about because it is unkind?"

"Unkind to who? All those Indians are dead."

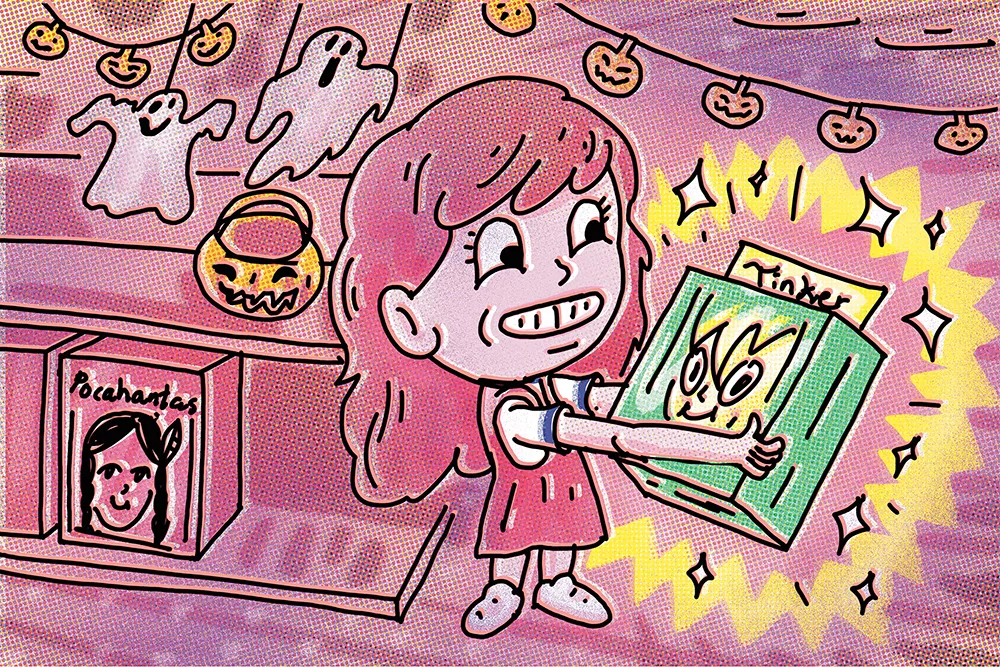

"Mama," I say. I am six, we are at Kmart. The costumes in 1978 came in boxes with windows that looked in on a plastic mask to cover the face which lay upon a neatly folded polyester garment to cover the body. "I want to be Tinker Bell."

"But you didn't even like Peter Pan," my mom replied, her hand holding mine, pulling me toward a dog costume, my passion second only to unicorns.

I pulled back. "Please?"

I imagined showing up to class wearing the fair skin, the yellow hair. My mom could tie my dark braids behind my head, and I would wear a white turtleneck beneath the yellow and green dress. Then, when Mrs. Sena led our kindergarten class around the lunchroom for our annual Halloween Parade, I would be indiscernible from the other kids.

For a day, none of my classmates would call me Cindian.

"Cindyjawea."

My brother and his partner laugh and shake their heads. I have just told them the name I was given on a five-night canoe trip down the Smith River in Montana. We are having dinner at their apartment in D.C. where I have traveled to attend an Indian Education training. We are talking about Halloween, pejoratives, and an encounter I'd had months earlier with a local sheriff who insisted he knew every Indian that's in Idaho County.

"But you don't look like an Indian."

The three of us turn our attention to the man seated across the table from me.

"What does an Indian look like," I ask.

"You know," he said. And begins to describe an outfit, a darkness of skin, two braids.

"It's not your long braids," he continues, and I smile. "It's not your skin or some turquoise or beads you might wear."

I shift my weight on the bench sensing the gravity of what he is about to say.

"I know you're Indian because you fight for Indians."

"Snow White" I say when my co-worker asks, "Well, who will you dress up as?"

"Snow White?" She repeats and looks at me, brows furrowed, as if trying to see the costume already on my body, "But you aren't..." ♦

CMarie Fuhrman is the author of Camped Beneath the Dam: Poems (Floodgate 2020) and co-editor of Native Voices (Tupelo 2019). She has published poetry and nonfiction in multiple journals as well as several anthologies. She resides in the mountains of west-central Idaho.