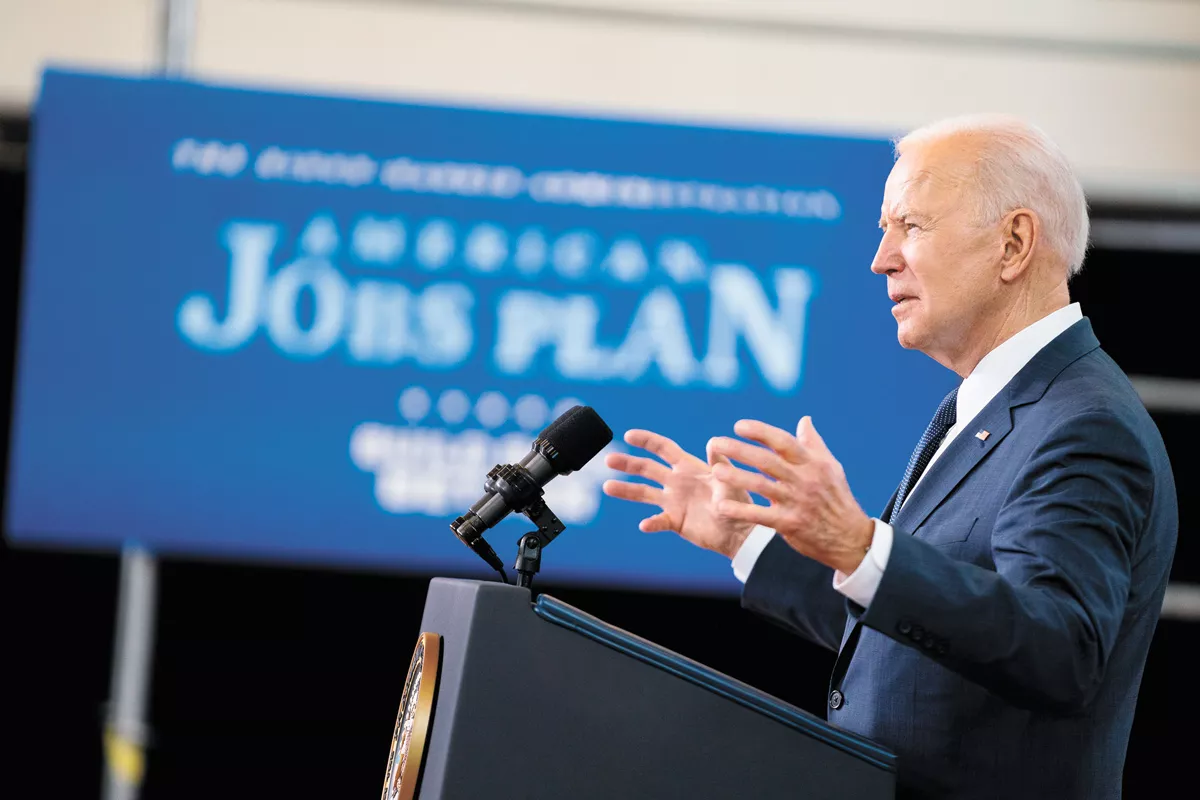

Last month, President Biden unveiled his ambitious $2 trillion infrastructure plan as part of his broader promise to "Build Back Better." Much of the plan invests in traditional forms of infrastructure. It includes money for repairing crumbling bridges and roads, investment in public transport (Biden's beloved Amtrak) and the electrical grid, as well as 21st-century infrastructure, like electric cars and high-speed internet. Former President Trump had promised much the same thing during his 2016 campaign, but without delivering on them once he was in office.

But Biden's plan moves beyond Trump's broken promises by embracing a broad definition of infrastructure that includes things like support for home care for the elderly and disabled, child care, veterans' hospitals and technological research. Democrats argue that this "human infrastructure" is an essential part of improving the everyday lives of ordinary Americans and promoting a robust economic recovery from the pandemic.

Biden will not be the first president to pursue an ambitious infrastructure program in the midst of a crisis. Abraham Lincoln did the same thing during the Civil War. As the future of the United States hung in the balance in 1862, Congress passed the Homestead Act, the Pacific Railroad Act and the Morrill Act. These three acts promised to remake the United States into a transcontinental economic powerhouse by providing a broad platform of federal support for the commercial development of the West.

The Homestead Act is arguably the most comprehensive redistribution of wealth in American history. Embracing the Jeffersonian ideal of an expanding republic of independent small agricultural producers, the act essentially offered free land to almost anyone, including single women, free African-Americans and even unnaturalized immigrants. Between 1862 and the last homestead grant in 1988, the United States government gave away over 270 million acres of land, including homesteads in Washington and Idaho.

Lincoln recognized that distributing homesteads would not be enough to promote the economic development of the West. The Pacific Railroad Act authorized the construction of the United States' first transcontinental railroad. If homesteaders were to succeed as commercial farmers, they would need access to markets where they could sell their produce. Completed at Promontory Point in the Utah Territory in 1869, the first transcontinental railroad provided the transportation infrastructure to move people and goods across the nation.

Public education was also a core element of Lincoln's infrastructure plan. The Morrill Act set aside public lands to establish "land grant" colleges and universities in the West. Today, you will find land grant universities in all 50 states, D.C. and five U.S. territories, but in 1862 the Lincoln administration saw these institutions functioning as economic engines for Western commercial development. WSU was founded in 1890 as the "Agricultural College, Experiment Station and School of Science of the State of Washington." Its mission was to engage in research and public outreach to provide homesteaders with access to cutting-edge agricultural expertise and technology.

Why would Lincoln pursue an expansive infrastructure program during America's greatest time of trial? Lincoln was a politician. With most Southern slaveholders gone from Congress, he recognized that the time was right to deliver on the Republican Party's commitment to "internal improvements," as infrastructure was known in the 19th century. But these measures were more than simple political opportunism. They marked America's commitment to the dignity of labor for all. Lincoln's infrastructure program worked hand-in-glove with the Union Army to build an America that worked for ordinary people, not an entrenched aristocracy of slaveholders.

Biden's plan needs to embrace this same ethic in imagining the future of infrastructure in this country. The pandemic crisis has revealed many of the weaknesses of our society and economy. Some Americans have access to high-speed internet for Zoom meetings and online learning. Many do not. Some Americans were lucky enough to have a support structure to manage their work lives while homeschooling their children. Many do not. Reliable internet access and child care are no less important to rebuilding our national economy than interstate highways and bridges.

But there are also lessons that Biden can learn from the Lincoln administration about what not to do. The millions of acres of land that the United States distributed to homesteaders was taken from Native homelands, acquired by treaty and coercion. The laborers who built the transcontinental railroad were often poor, marginalized immigrants from China and Ireland. It is heartening that Biden's program includes labor protections, because we must make sure that by building back better, America looks out for everyone. ♦

Lawrence B. A. Hatter is an award-winning author and associate professor of early American history at Washington State University. These views are his own and do not reflect those of WSU.