Washington has the fifth-highest homeless population in the country. We trail only the states of California, Texas, Florida and New York. In response, Gov. Jay Inslee has asked state lawmakers for another $815 million on top of the roughly $2 billion they agreed last April to spend over two years on housing and homelessness. If Inslee's latest request passes, our state will spend over $120,000 per homeless person in Washington, and that doesn't include what cities and counties spend.

Resources are needed, but the solution isn't just more money. Our state's failure to provide basic education, mental health and foster care services, and our permissive policies toward drugs and camping in public spaces, partially created this mess.

Our mental health system is ranked somewhere in the bottom third. Our foster care system warehouses kids in motels and cars. Washington is ranked third in adult drug users, but 51st in people receiving substance abuse treatment. The education many poorer kids receive too often does not prepare them for independent living. Before spending another $815 million, we should demand our elected leaders acknowledge these failures and implement reforms. That requires tackling the root causes.

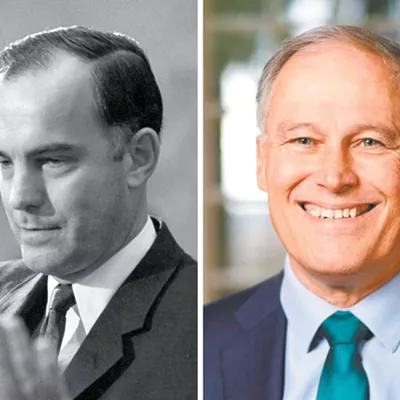

For the last two decades, I've grappled with how best to help the homeless in our midst. Around 2001, I started volunteering as an overnight manager of a Seattle shelter for men. Later, as an elected official, the issue landed on my desk. As a gubernatorial candidate, I visited and worked shelters and soup kitchens across our state. My experiences reinforced that homelessness is a statewide issue. The recent episode at the Spokane Convention Center reveals that. My experiences also taught me that the myriad reasons people are homeless form a Rubik's cube that's tough to solve.

Helping some is straightforward. Those who find themselves homeless after losing their job or having their rent increase, those who have struggled with addiction or divorce and are seeking help, these people we can help.

Those who grew up bouncing between rentals and shelters and friends' floors, who've never had a checking account, who don't know how to budget, these people probably couldn't keep either an apartment or a job if they were given both. Helping them requires tailored services, but if they want help, there is a pathway forward.

But too many don't want help, and this is where solving the cube becomes mind-vexing.

One night at the shelter, I overheard three friends talking about how once it got 10 degrees warmer they'd move back to the park. When these men left the shelter in the morning, they went to jobs, but they liked the freedom of camping in the park during warmer months.

Solving homelessness requires confronting the reality that some people, especially some single men, choose to camp.

One man told me he'd once had a family, suburban house and job, and he said he'd never return to a full-time job or monthly bills. He preferred living outside, and when it got too cold, in a shelter. Without counseling, I couldn't see how giving him an apartment he'd eventually have to pay for would ever succeed. And he didn't want counseling.

As president of the Seattle Port Commission, I had to resolve several dozen people camping in one of the port's waterfront parks and demanding the port give it to them. The port explained that legally it could not give public property to private individuals, nor could it legally allow camping on that shoreline. They were given a deadline to leave. The night before their tents were to be cleared, I sat with the "residents," listened to their stories and assured them the port had located shelter for everyone who wanted it. Most took us up on the offer. The next morning the camp was cleared; a few were arrested.

No other decision I made as an elected official so forced me to reconcile my commitment to social justice with my responsibility to uphold the law. Pope John Paul II urged us to have "a special openness with... those who are humiliated and left on the margin of society, so as to help them win their dignity as human persons.'' Some argued that, legal or not, we should let them stay, but I came to believe that enabling people living in filthy, drug-infested camps was abandoning them to the margins of society.

Years later, as a gubernatorial candidate, I was talking with a few Seattle cops who told me they thought tolerating camps made homelessness worse. They talked about how some of the kids who ended up in the camps had been kicked out of their homes, run away, or "graduated" out of the foster system at 18. They said that if you didn't have a drug or mental health problem going into those camps, you would after a few weeks there.

Most homeless people don't live in camps, but these tented villages are emblematic of the dank, tangled, wicked thicket of abuse, trauma, drugs and mental illness too many of the homeless do live in.

Janet lived in that thicket. I met Janet while walking in SoDo in Seattle. She pointed to a tent she shared with two guys. She had a part-time job at the ballpark, had cancer and struggled to take her medicine as prescribed. When I asked why she didn't find help at a shelter, she told me she didn't want to leave the guys, and she didn't want to follow shelter rules. I am guessing, but I bet drugs were involved, and who knows what her relationship was with the guys. While Janet had "chosen" to live in the tent, unlike the three men I'd overheard in the shelter, she didn't appear capable of making rational decisions. It also didn't appear that she would accept help, at least not that day.

Another group of people who need help but are not in a state of mind to accept it are those addicted to meth or heroin. One of the most gut-wrenching meetings I've ever sat through was with parents whose children were somewhere on Seattle's streets. Each dreaded the call to come identify their child's body. As a gubernatorial candidate, they were urging me to oppose safe injection sites and low-barrier shelters, which along with Seattle's permissive attitude toward drugs, they thought only enabled their kids' life on the streets.

Homelessness is not one problem but many problems demanding different solutions. More resources could be spent, but we should only allow elected leaders to spend more money if they reform services we've neglected for decades. That neglect is now spilling out onto our streets.

There is one more thing we can do. When you see a homeless person, make eye contact and say hi. It can be uncomfortable, but the first step in getting someone to seek help is showing them they have value and dignity.

It's not going to solve the problem, but it's a start. ♦

Bill Bryant, who served on the Seattle Port Commission from 2008-16, ran against Jay Inslee as the Republican nominee in the 2016 governor's race. He is chairman of the company BCI, is a founding board member of the Nisqually River Foundation and was appointed by Gov. Chris Gregoire to serve on the Puget Sound Partnership's Eco-Systems Board. He lives in Winthrop, Washington.