Julian Aguon opens his new book by reminding us that, if the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is to be believed, we have about 10 years left to get our collective shit together.

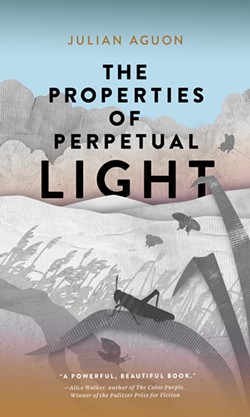

It’s a weighty reminder, and one that feels almost paralyzing. What can an individual possibly do when faced with gargantuan forces like climate change, nuclear warfare and the American imperial project? The three symbiotic specters loom heavily over Aguon’s new book, The Properties of Perpetual Light, and while Aguon doesn’t pretend to have solutions, his intimate portrait of childhood in Guam does offer something close — hope.

Aguon is an Indigenous Chamorro human rights lawyer and founder of Blue Ocean Law, a progressive law firm that focuses on Indigenous rights and environmental justice. He grew up in Guam, an island in the Marianas archipelago that has been an American territory since 1898. Decades of military occupation have caused severe environmental degradation and the U.S. Department of Defense, which owns roughly 30 percent of the island, continues to build new military bases despite opposition from local activists. The American militarization of Guam was a constant presence in Aguon’s childhood. The occupation and its resultant grief haunt his book as well.

Aguon describes Properties as a love letter to young people, who he says are deeply passionate about the injustices around them but sometimes lack the vocabulary to express it. By offering his own stories of youth and vulnerability, he hopes to help equip the next generation with the tools they’ll need to tell their stories and navigate the long road to justice and repair.

“I think that’s part of what sharing our vulnerability does; it anchors us. It encourages us or shows us the need to respect strength and not power,” Aguon tells the Inlander.

Properties eschews traditional narrative, instead jumping between essays, poems, eulogies, graduation speeches and political commentary. When writing the book, Aguon says the nontraditional structure felt necessary in order to communicate the ideas he was focused on. Some sentiments can only be communicated through certain mediums, he says.

“In some ways the book is just the kind of book that refuses to obey,” he says. “There’s only so much I could graft my will onto the book — it sort of revealed itself to me.”

The lack of traditional structure also lends itself to the mammoth issues tackled in the book. Each section stands on its own, but when taken together, the effect is one of powerful resistance: A chapter that eulogizes Marshallese statesman Tony de Brum and explores the legacy of American nuclear testing is followed by a poem about the gaosåli flower; a short story about fishing in the moonlight feels downright radical when put in conversation with the subsequent chapter, a blistering op-ed on the destruction of hundreds of acres of limestone forest to accommodate a live-fire training range. (The act is carried out by Caterpillar bulldozers, which, as Aguon grimly notes, share a name with the creature whose habitat they destroy.)

When writing about the environmental destruction wrought by one of the largest military buildups in modern history, focusing on something as simple as a flower almost feels like the only logical response. Aguon says he was inspired by author Arundhati Roy’s idea that the smallest of things connect to the biggest.

“I’m kind of trying to look at the world from a very different perspective, from the perspective of the small, the perspective of the vulnerable,” Aguon says. “And to get that perspective you have to get really close to the earth; get really down and get lowercase earth under your fingernails.”

In Properties, Aguon frequently draws on the work of other activist writers, including Audre Lorde, Alice Walker and Toni Morrison. In a chapter titled “Sherman Alexie Looked Me Dead in the Eye Once,” he writes about Sherman Alexie, a Native American novelist from Spokane who rose to national prominence with his book The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.

In a footnote, Aguon explains that he was hesitant to include the piece because of troubling #MeToo allegations against Alexie, but that he ultimately decided to include it because of the formative impact Alexie had on him as an aspiring Indigenous writer. (In 2018, a number of female authors accused Alexie of leveraging his fame and sexually harassing them; Alexie released a statement apologizing for his actions while denying some aspects of the allegations.)

“The footnote is just as important as the piece, you know, because I also wanted to show young people that, too — the sitting with the unresolved tension. It’s almost like I want to encourage young people not to forsake the bigger confusion from this smaller certainty,” Aguon says.

Aguon says he made a special effort to quote from Oceanian writers like Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner, who are on the front lines of the climate crisis. For residents of low-lying island nations in the Pacific Ocean, the threat posed by rising sea levels has already reached existential levels.

“I think that we have to center those perspectives because they’re the ones who offer the most urgency, and it’s that that can hopefully recalibrate the global conversation on climate change and the sort of inadequacy of our actions to date,” Aguon says.

Philosopher Timothy Morton has described the climate crisis as a “hyperobject”: a thing so vast and all-encompassing it literally excedees human comprehension. We’re able to talk about it and notice its effects, but the scale of the issue defies action.

“It’s like a bullet train, and it’s headed straight for us, we’re not even moving out of the way,” Aguon says.

The science on climate change is clear, so why are we still standing on the tracks? Part of the reason, Aguon says, is because we aren’t telling a better story. In a chapter titled, “We Have No Need for Scientists,” Aguon rebuffs the cold detachment of the data-driven scientific establishment.

“We have forgotten that there are two kinds of information. We’re stuck in the facts; we’re lost in a forest of facts. We have enough facts, enough evidence, but it’s not been enough to compel people,” Aguon says. “It hasn’t been enough to move hearts and to change minds and change behaviors. But art — artists help bridge that gap.”

Earlier this month, nearly 800 Pacific Northwesterners died in a heat wave that scientists say was directly linked to human-caused climate change. Powerlines melted, rivers ran low, and millions of shellfish were cooked alive in their shells. As is routine, the damage was unevenly dispersed on vulnerable communities.

Those are facts. It’s up to young people to find the story.

Julian Aguon will be joined by author Tommy Orange for a Zoom event at Auntie’s Bookstore on Thursday, July 22, at 7 pm. Orange is a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations of Oklahoma. His first book, There There, was a finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize and a recipient of the American Book Award. Attendants can register for free at auntiesbooks.com.