Brenda Hester is trying to corral a group of giggling, distracted 12- and 13-year-olds.

"My group, over here! You're not in my group — I just need my group," she tells a confused bunch and points them across the gallery.

It's the second-to-last day of school and Hester, a Medical Lake Middle School social studies teacher, and a few colleagues are trying without much success to keep the attention of the school's 125 seventh graders as they tour the galleries housing the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture's current exhibit, 100 Stories — A Centennial Exhibition.

The two-year exhibit, on display through January 2016, celebrates the 100th anniversary of the Eastern Washington State Historical Society, more familiarly known as the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture (aka the "MAC"), by telling the past century of our region's history through 100 objects and places — some as far away as Grand Coulee Dam — with 100-word descriptions of each artifact.

The Medical Lake students spent the school year studying Washington state history, and though their attention spans on a recent Thursday are short, many make observant discoveries as they roam the exhibit — "Oh look, it's Bing Crosby!" Some even studiously fill out museum-provided exhibit question booklets in pencil.

From historical photos by famed early Spokane photographer Charles Libby and a Japanese-American bride's dress worn for a Dec. 7, 1941, wedding to elaborate Native American beadwork, 100 Stories is sort of a "greatest hits" collection of the MAC's archives.

"The beauty of 100 Stories is that each story could be its own exhibit," says MAC director Forrest Rodgers.

Many of the artifacts have been displayed in the past, but mixed in are several newly exhibited items, like a massive woolly mammoth tusk unearthed in the area years ago, and an animated neon sign from a 1970s-era record shop in downtown Spokane.

One of the top challenges for the museum's curatorial team was narrowing down its massive archives to the exhibit's 100 highlights while fulfilling numerous criteria. 100 Stories needed to represent all decades of the past century, not just the turn-of-the-century boom years, which are widely represented in the MAC's collections.

The story mix also needed to show major events and examples of everyday life during different eras. Another consideration is showcasing a diverse mix of the region's cultural groups, and evenly representing men and women. An example of this was choosing to show Fairchild Air Force Base's regional influence through the stories of women in the military.

"We wanted to tell the stories that we could best tell with our unique collection," says museum collection curator Valerie Wahl. "We couldn't tell comprehensively everything that's happened, but we're telling the stories we can tell best."

That also meant incorporating pieces from the museum's fine art collection alongside historical artifacts and photographs, Wahl says.

"It's a different way to reflect people of the region. Most of the art in the collection, the artist has a tie — they live here now and spent their career here, or they were raised here," she adds.

There's no doubt that the artifacts collected and preserved over the past century would be much fewer and different in scope if the Eastern Washington State Historical Society hadn't been formed in 1916 by a group of local teachers (originally called the Spokane Historical Society).

Ten years later in the mid-'20s, the society moved into the Campbell House — still part of the museum campus in Browne's Addition — and began receiving state funding as a designated trustee of the state, tasked with preserving and sharing the Inland Northwest's distinct history. In 1960 the museum moved to the adjacent Cheney Cowles Memorial Museum, where it stayed until 2001 when it rebranded as the MAC with the opening of a new exhibit and gallery facility.

Though the organization has more recently struggled with repeated state funding cuts, drops in local donations and staff departures, the MAC presses on, looking toward its next 100 years.

As much as 100 Stories seeks to reflect upon the history of the past century, just as important is its purpose to look ahead.

Says Rodgers: "What will people who come here in the future think about this place and know about this place?" ♦

One Man's Trash

The rich, jewel-tone hues of the glass range from glowing amber to a foggy peridot, and include shades of emerald, sapphire and quartz. Embossed into some of the smallest bottles, raised lettering spells out the word "poison." Others are more specific: "C. Damschinsky Liquid Hair Dye, New York," "Spokane Soda Bottling Works" and "Broadview Dairy Co."

There are more than 60 bottles in a long, backlit case on the landing of the stairs down to the museum's gallery, but this is only a small fraction of Brian Martin's personal collection of 13,000 items, all recovered from an early Spokane dump site.

The items Martin collected over two decades, through the 1980s and '90s, now provide a glimpse into the past that tells us what Spokane's early residents drank, ate, imbibed, medicated with and then discarded. Most of the trash, estimated to have originated between 1880 and 1930, was burned before being dumped into the ground along the banks of the Spokane River, in a spot east of Division where the Riverpoint Campus has since risen from the dirt.

After the land was sold with the vision to become a downtown University District, and before construction began and forever sealed the earthen vault, it was a prime digging spot for treasure seekers like Martin. Digging as deep as 20 feet down, he'd carve out notches in the walls of the holes so he could haul up buckets of dirt and the good, unbroken finds. He mostly dug in the winter because the soil was damp and easier to cut through. Most of the time, no one was bothered by the treasure hunters. Martin and other bottle diggers came and went freely.

Some of the other diggers would take their best finds directly to a nearby antique shop on East Main Avenue and sell them for cash. Not Martin.

"They were worth something, either because of the name or the color of the glass. I didn't do it for that reason. I kept everything I ever dug," he says.

Among the antique glass bottles and other containers, Martin found fully intact, preserved china from the Davenport Hotel — a teacup, coffee cup and a few other pieces thrown out with broken dishes. He also found "territorial bottles," inscribed with the origin of "Spokane Falls, W.T." when the region was still part of Washington Territory.

A century ago this was all trash. To Martin, it's all buried treasure.

— CHEY SCOTT

The Champion's Blanket

Proctor Knott would win. That's what everyone said (and most of them bet) at the 1889 Kentucky Derby. Proctor Knott — a proven winner and the pride of Kentucky, hailed as the finest runner ever seen in America. Who could beat him?

And sure enough, the horses were off, and there was Proctor Knott lunging ahead of Hindoocraft after the first quarter and nearly unseating his jockey in the effort. At that time the race was a mile-and-a-half, and Proctor Knott led by five lengths on the final back stretch. But then — a sharp break to the outside rail, and up the inside came Spokane, a chestnut colt out of Montana. Halfway down the final stretch, Spokane pulled even with Proctor Knott and the two passed under the string at the same moment on opposite sides of the track.

Noah Armstrong, a Montana mining baron and horse breeder, had been visiting Spokane Falls when he received news that his mare Interpose had given birth to a colt, the son of the great Hyder Ali. Armstrong named the foal Spokane.

Three years later at the Kentucky Derby, after long deliberation by the judges, Spokane was declared the winner. The decision was met with silence in the stands. It was said that some betting Kentuckians did not pay off the debt for 25 years. But news reached Spokane Falls with enthusiasm and pride, and the businessmen of the city raised $5,000 to have a champion's blanket created for the horse.

Spokane went on to win the Clark Stakes, also at Churchill Downs, two weeks later, and then the American Derby in Chicago the following month — the equivalent to winning today's Triple Crown.

"It was a grand struggle, a veritable battle of the champions, that is, as far as the three-year-olds of this country are concerned," a sportswriter wrote from Chicago. "And now Spokane is king."

The champion never won again, and within a month the city he was named after went up in flames in what is now known as the Great Fire. But because the length of the course was shortened several years after Spokane's victory, he continues to hold the Kentucky Derby record for the fastest race ever run at that distance.

— LISA WAANANEN JONES

The Guest of Honor

The dolls arrived in the U.S. in time for Christmas 1927, each of the 58 nearly three feet tall with kimonos made of silk and luminous skin made of powdered shell. Earlier that year, thousands of blue-eyed dolls were sent from the U.S. to Japanese children in a gesture of friendship, and more than two million Japanese children donated sen — their pennies — to have dolls sent to America. The Japanese dolls toured the nation, then were distributed among the states to libraries and museums.

"The Committee on World Friendship among Children desires to have the dolls so located and treated as to convey their messages most effectively to the American children," the committee wrote in a letter. "With this in view, it wishes to make sure that each museum that receives one of the dolls fully understands the situation and will help to make their presence a continual reminder to our people, and especially to our children, of the goodwill gesture of the children of Japan."

Then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and the war was not kind to the dolls on either side of the Pacific. A few were damaged intentionally; most were simply put away or forgotten. In recent decades, many have been recovered and found — in flooded basements, cardboard boxes, auction houses — but a dozen remain lost. Miss Aichi, location unknown. Miss Kobe, location unknown. Miss Tochigi, location unknown.

Miss Tokushima, bestowed upon Spokane, endured the war in a storage vault, and still has her tiny, expertly crafted accessories. In 2011, she returned to Japan in her original travel trunk, where she was acquainted with Alice, the blonde, blue-eyed doll sent to Tokushima by American children. Each March, Miss Tokushima travels from the MAC to the Mukogawa Fort Wright Institute, where she is an honored guest for Hina Matsuri, the annual doll festival.

— LISA WAANANEN JONES

The Murder Weapon

On the night of Sept. 14, 1935, Newport town marshal George Conniff interrupted burglars stealing from a local creamery. He was shot four times and died a few hours later. "Several new clews (sic) were uncovered this morning, but no trace of the bandits or their identity has been found at noon," the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported two days later, the day of Conniff's funeral.

The crime went unsolved for more than 50 years. Then, in the 1980s, Pend Oreille lawman Tony Bamonte starting looking into the murder during research for his master's degree at Gonzaga. The story he learned — from a deathbed confession, old police reports and aging witnesses — was that of a long-ago police cover-up. The murderer was one of their own, a former detective named Clyde Ralstin, who was profiting off the Great Depression with a black-market butter scheme in an era of rampant corruption.

But stories are one thing, and evidence is another. Bamonte had statements from two officers who were told to throw a package off the Post Street Bridge because another officer was "in trouble of some sort." Bamonte suspected the murder weapon could still be found; officers assigned to the reopened investigation were more skeptical.

In August 1989, Washington Water Power stopped the falls. In just five minutes, Bamonte found a pistol on the riverbed, exactly where the retired detective had told him it had been dropped. After decades underwater, the handle had disintegrated and the metal was corroded. "I found what I expected to find," Bamonte said at the time.

Ralstin, nearly 90 years old and living in Montana, told the Spokesman-Review the whole thing was "hogwash." He died a few months after the pistol was found. Bamonte donated it to the museum, along with other artifacts from his research, where it serves as a symbol of justice dredged out of history.

— LISA WAANANEN JONES

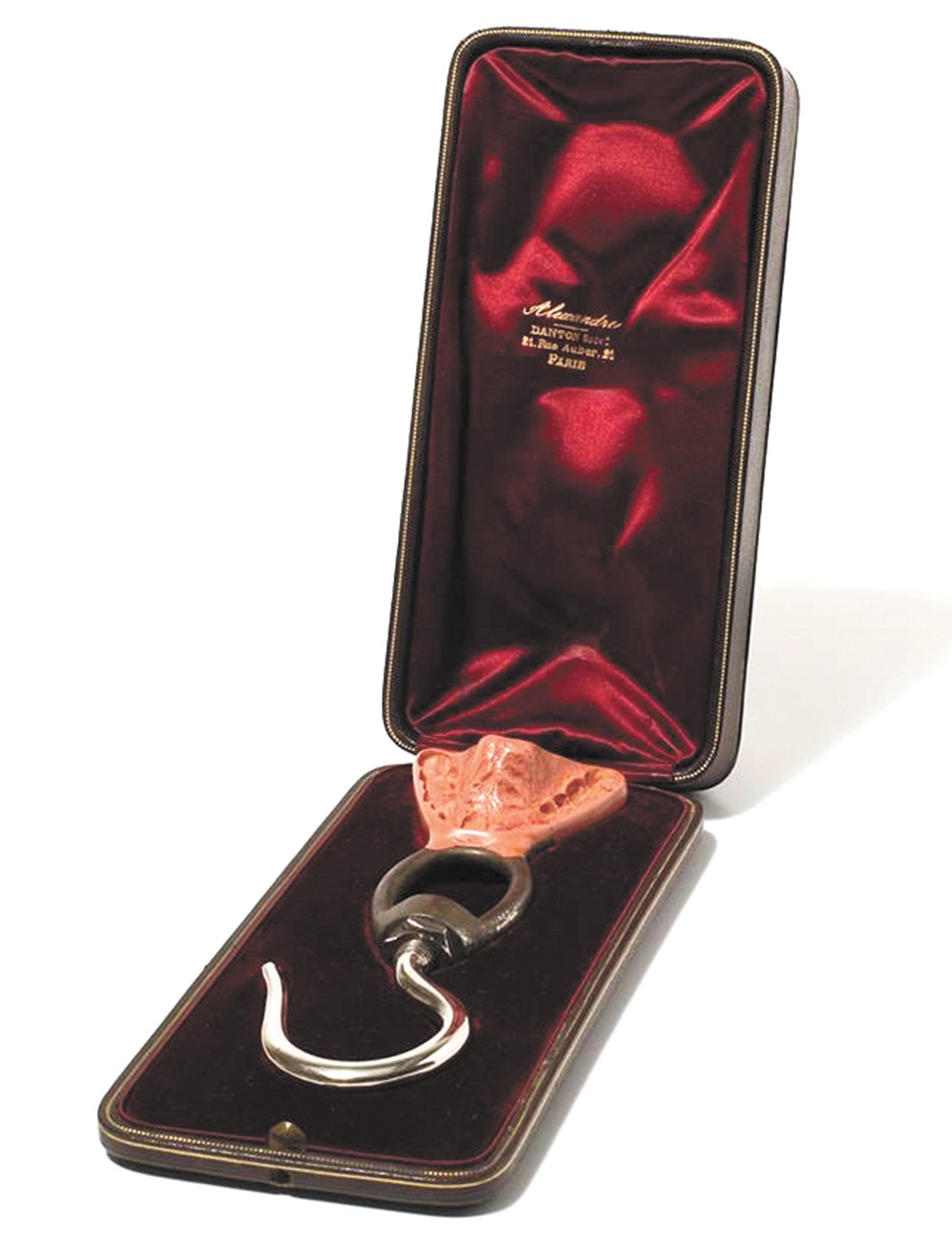

The Acrobat with an Iron Jaw, c. 1890

After injuring her teeth in Germany, Leona Dare retired the hooked mouthpiece from which she had dangled underneath hot-air balloons around the world. Though this American trapeze artist and aerial acrobat was most famous for this shocking "iron jaw" act, her career was just as risky as it sounds, made evident by the death of the partner she dropped while performing in Spain. She ended up dying in Spokane in 1922 after following family to the area, leaving behind many of her belongings. (FRANNY WRIGHT)

" ... A Better Spokane," 1981

James Chase came to Spokane during the Great Depression, riding the rails from his home in Texas in search of opportunity. He shined shoes, did repair work during World War II and in 1975 became the first black member of the Spokane City Council since the city's early days. In 1981, he was elected the city's first black mayor. "He found a city that he could love, and that could love him, for the rest of his life," former Mayor Vicki McNeill said at the memorial service when Chase died of cancer in 1987. Glenn Mason, then the director of the museum, spotted the cardboard sign at a yard sale in the '90s and made it part of the collection. (LISA WAANANEN JONES)

Sign of the Times, 1973-78

In the 1970s and early '80s, the Magic Mushroom sold records, waterbeds and other paraphernalia. The sign is on display for the first time at the MAC, following a restoration that makes it fully work again. (LWJ)

Boots at Work, 1980

During his summer employment at the Kaiser aluminum plant, Michael Cain and his coworkers wore these heavy work boots, supplementing their soles with scraps of rubber tires in an attempt to withstand the heat that rose from the job site. Cain, who worked at the plant in 1980, was one of thousands employed at Kaiser's Mead smelter during its 50-plus years of operation. Weighted under the debt of production costs, the plant closed in 2000. These days, the site is under demolition and redevelopment. (JENNA MULLIGAN)

All That Remains, 1889

The Great Spokane Fire of Aug. 4, 1889, drastically changed the landscape of downtown Spokane Falls, ravaging 32 city blocks in just a few hours time. But that devastation paved the way for many of the iconic buildings erected to replace those lost, many of which still stand today. The fire caused millions of dollars worth of damage, and newspaper headlines proclaimed: "The Entire Business Portion of the City Wiped Out of Existence" and "A Night of Terror, Devastation, Suffering and Awful Woe." After the smoke had cleared, the National Guard was called in to protect the "burnt district" from looters, handing out passes to property owners looking to claim anything left. Local real estate broker Daniel Dwight obtained one of these passes to collect souvenirs from the decimated block where he'd owned a building. There he picked up a fused mass of colorful poker chips he donated to the museum in 1939. (CHEY SCOTT)

Grab the Gold Ring, c. 1909-68

West of downtown, along a deep bend in the Spokane River lined with mobile homes, it's hard to picture a turn-of-the-century park filled with amusement rides and sounds of merriment. Yet the defunct Natatorium Park lives on, its crown jewel now residing in Spokane's modern central gathering place — Riverfront Park. The Looff Carrousel was originally ordered for $20,000 by the park's original owners, but after their bankruptcy it became a gift from the famed carousel maker Charles I.D. Looff to his daughter, Emma, who coincidentally moved to Spokane to wed Louis Vogel, a banker. It was installed at Nat Park on July 18, 1909, and remained there until the park was shuttered and razed in 1968. After Expo '74 wrapped up, the attraction was moved from storage into its current 10-sided shelter on the waterfront. To this day, lucky riders who grab the gold ring still earn the traditional free ride. (CS)

Turning the Earth, c. 1879

In contrast to today's sprawling suburban developments, at one time the area north of Spokane's core was wild and wooded, grassy and empty. As pioneers poured into the region to homestead and try their luck on the Western Frontier, the U.S. Homestead Act allowed newcomers like Emil Johnson to claim federal land grants for farmable land. Johnson bought a sleek new plow from a downtown hardware store and hooked it to up to his team of between six and eight horses. That many were needed to break the dense, virgin sod of the Peone Prairie, located in the picturesque shadow of Mt. Spokane. (CS)

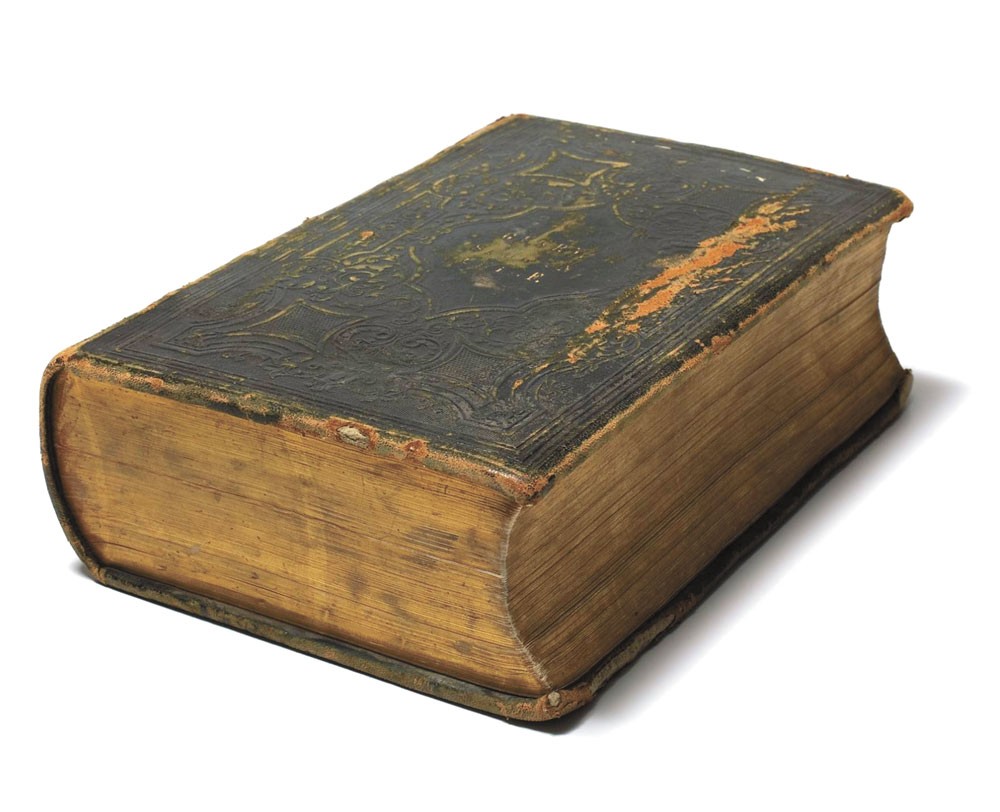

The Chief's Bible, 1868

As a boy, Spokane Garry was one of two young Native Americans chosen by the Hudson's Bay Company to study at a mission school, where he learned English and Protestant Christianity. He spent many years spreading Christian teachings and negotiating peace between the Spokane Tribe and the white settlers. But by the end of his life, living homeless in the woods of Indian Canyon, he'd lost his land, his wealth and the respect of Spokane's new powerful men. He died in 1892 with little besides his Bible. His great-great-granddaughter preserved the well-worn Bible, and her family donated it to the museum in her memory. (LWJ)

Ancient Residents, c. Ice Age

Homesteaders in the Inland Northwest unearthed massive, mysterious bones — remnants of the mammoths caught in the Ice Age floods that covered the region. Because it was long ago separated from any information about its exact origins, the mammoth tusk in the MAC's collection has never been displayed until now. (LWJ)

Child's Play, c. 1900-12

A pair of bisque porcelain dolls from Helen Campbell's personal collection are traced to Bavaria or Germany, where the Campbell family visited during a European tour in the early 1900s. The museum also acquired one of third-generation German toymaker Albert Schoenhut's complete safari sets, one of many sets crafted between 1909 and 1912, and themed after President Teddy Roosevelt on holiday in Africa. Additionally, an intricately handcrafted Native American "Old Sophie" doll has actual human hair. (JM)

Plateau Expressions, c. 1880-1950

The 30 hand-beaded bags on display in a large glass case along one gallery wall are breathtaking. The intricate work, the talent of Plateau Tribe craftspeople, seems ahead of its time, and brings to mind imitated or replicated handbags that women still carry today. About half of the bags were donated to the museum in 1962 as part of the extensive, 1,427-piece Chap C. Dunning Memorial Collection; Dunning was a prolific collector of American Indian cultural pieces. (CS) ♦